Chapter 13 The effects of aging on behavior in senior pets

DISTRIBUTION OF BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS IN SENIOR PETS

CAUSES OF SENIOR PET BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS

COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION AND BRAIN AGING

AGING AND ITS EFFECT ON THE BRAIN

DIAGNOSIS OF BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS IN SENIOR PETS

TREATMENT OF COMMON BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS IN SENIOR PETS

TREATMENT OF COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION

AGE-RELATED COGNITIVE AND AFFECTIVE DISORDERS (ARCAD)

BEHAVIOR DISORDERS IN AGING DOGS: PAGEAT (FRENCH) DIAGNOSES AND TREATMENT

As pets age, there are likely to be an increasing number of health concerns where a change in behavior is noticed as the first sign of illness. In fact, for some of the more common medical problems associated with age, including pain, sensory decline, and neurological diseases, such as cognitive dysfunction, the only presenting signs might be behavioral (see Box 6.1 for medical causes of behavioral signs). Therefore, family members will need to be counseled as to the significance of these changes and the importance of reporting these promptly to their veterinarian. Early identification provides an opportunity for early diagnosis and treatment, so that complications may be prevented, further decline slowed, longevity increased, and welfare issues promptly addressed.

Behavioral signs such as changes in activity levels, altered responses to stimuli, altered social interactions, anxiety, altered sleep–wake cycles, housesoiling, confusion, or memory deficits may arise as a result of brain aging (e.g., cognitive dysfunction syndrome or CDS). These signs are commonly referred to by the acronym DISHA, which corresponds to disorientation, changes in social interactions with family members or other pets, sleep–wake cycle alterations, housesoiling, and activity level changes. CDS is a diagnosis of exclusion in that other primary medical or behavioral problems that might cause or contribute to these signs must first be ruled out. In addition, senior pets can have multiple concurrent problems, making diagnosis much more challenging.1

Distribution of behavior problems in senior pets

Studies of case distribution of behavior problems in senior pets give some indication as to the most serious owner concerns. However, this can be misleading since many of the more common or subtle behavior changes seen in the home environment often go unreported. In fact in one study the prevalence of cognitive dysfunction as diagnosed from a questionnaire was 14.2% of all dogs 10 and over with 41% of dogs over 14 affected. Yet, a veterinary diagnosis had only been made in 1.9% of cases, and 85% of cases had not been identified.2

Cases reported to practitioners

In a Spanish study of 270 dogs over 7 years of age presented for behavior problems, 74% of the owners detected at least one behavior problem, two problems in 19.8%, three in 4.6%, and four in 1.3%. Thirty-two percent displayed aggression to family members, 16% aggression to family dogs, 9% barking, 8% separation anxiety, 6.4% disorientation, 6% aggression towards unfamiliar people, 5% housesoiling, 4.2% destructive, 4% compulsive disorders and 3% noise fears.3 Sixteen percent of these cases were diagnosed as CDS. In a second study at a behavior referral practice in St. Louis, of 103 senior dogs, 30% displayed separation anxiety, 27% aggression to owners, 17% aggression to other dogs, 8% compulsive disorders, 5% phobias, 4% anxiety, 3% housesoiling and 1% vocalization. Seven percent of these cases were diagnosed as CDS.4 When examining the distribution of behavior cases in dogs of all ages, aggression is by far the most common reason for referral with various forms of anxiety (independent of aggression) representing 15% of the cases or less, while in senior pets behavior problems associated with anxiety appear to be the most common reason for referral (Table 13.1).

Table 13.1 Canine senior case distribution compared to case distribution of all ages

| Behavior referral practice: n = 103 >7 years1 | VIN cases: n = 50 dogs (9–17 years) | Behavior referral practice: n = 1644 (all ages)2 |

|---|---|---|

| Separation anxiety 30% | Anxiety 74% | Aggression to people 60.6% |

| Aggression to people 27% | Cognitive dysfunction 62% | Aggression to animals 17% |

| Aggression to animals 17% | Separation anxiety 36% | Separation anxiety 14.4% |

| Compulsive disorders 8% | Wandering 26% | General anxiety 5.7% |

| Cognitive dysfunction 7% | Night anxiety / waking 22% | Unruly 12.2% |

| Phobias 5% | Noise phobias 18% | Housesoiling 7.5% |

| Anxiety 4% | Vocalization 14% | Phobias 3.9% |

| Housesoiling 3% | Stereotypic behavior 4% | Vocalization 2.7% |

| Vocalization 1% | Aggression 2% | Ingestive 1.4% |

VIN, Veterinary Information Network.

1Horwitz D. Dealing with common behavior problems in senior dogs. Vet Med 2001;96:869–887.

2Bamberger M, Houpt KA. Signalment factors, comorbidity, and trends in behaviour diagnoses in dogs: 1644 cases (1991–2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006;229:1591–1601.

In 83 senior cats referred for behavioral consultations, most cats displayed signs of marking or soiling (73%); however, cases of aggression (16%), vocalization (6%), and restlessness (6%) were also serious enough to require referral.1 When examining the distribution of behavior cases in cats of all ages, there appears to be a strong similarity in distribution, except for a relative increase in vocalization and restlessness in senior cats (Table 13.2).

Table 13.2 Feline senior case distribution compared to case distribution of all ages

| Behavior referral practices: n = 83 >10 years* | VIN boards: n = 100, aged 12–22 years | Behavior referral practice n = 736 (all ages)1 |

|---|---|---|

| Housesoiling 73% | Excessive vocalization 61% (night vocal 31%) | Housesoiling 56.8% |

| Aggression to cats 10% | Housesoiling 27% | Aggression to cats 25.8% |

| Aggression to people 6% | Disorientation 22% | Aggression to people 13.6% |

| Excessive vocalization 6% | Aimless wandering 19% | Ingestive 4.3% |

| Restlessness 6% | Restless / night waking 18% | Unruly 3.9% |

| Overgrooming 4% | Irritable / aggressive 6%Fear / hiding 4%Clingy – attachment 3% | Anxieties 2% Vocalization 1.4%Overgrooming 1.2% |

VIN, Veterinary Information Network.

*Cases recruited from behavior referral practices: Landsberg (n = 25), Horwitz (n = 33), Chapman BL, Voith VL (n = 25).2

1Bamberger M, Houpt KA. Signalment factors, comorbidity, and trends in behaviour diagnoses in cats: 736 cases (1991–2001) J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006; 229, 1602–1606.

2Chapman BL, Voith VL. Geriatric behavior problems not always related to age. DVM Newsmagazine 1987;18:32.

To examine further the distribution of problems reported by owners in senior dogs and cats, the Veterinary Information Network database (www.vin.com) was searched for the most recently reported behavior problems of 50 senior dogs (aged 9–17) and 100 senior cats (aged 12–22 years). In the dogs, there were 37 cases with signs of anxiety (fear, vocalization, salivation, destructiveness, hypervigilance); 18 with separation anxiety; 13 “wandering”; 11 night anxiety or waking; 9 noise phobias; 7 vocalizing; 2 with stereotypies; and 2 aggressive. Thirty-one dogs had signs consistent with CDS. In the cat cases, 61 were vocalizing excessively (31 at night); 27 had inappropriate elimination; 22 were disoriented; 19 were wandering; 18 were restless; 6 were irritable or aggressive; 4 were fearful or hiding; and 3 were more “clingy” with owners. Since any of these signs can be due to underlying medical problems, this demonstrates the importance of identifying behavioral signs in maintaining the health and welfare of senior pets. While cerebral disease, hypertension, sensory decline, pain, metabolic or endocrine diseases, anemia, neoplasia, drugs or viral agents (e.g., feline immunodeficiency virus) were all considered, in most cases these had been ruled out.1

Prevalence of behavioral signs in senior pets

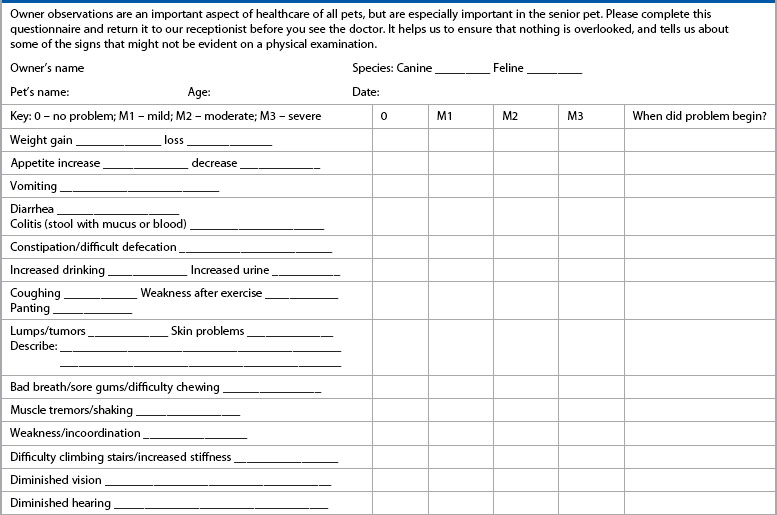

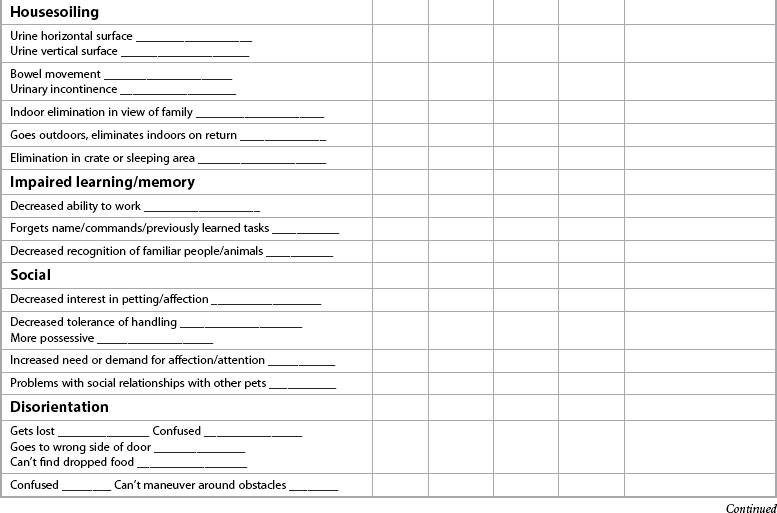

When focusing on the problems that are serious enough for pet owners to seek behavioral guidance, it is much more common for senior pets to go unreported unless practitioners take a more proactive approach in educating pet owners about the significance of behavior changes in older pets and actively inquiring about their presence. In 2005, the American Animal Hospital Association (www.aahanet.org) senior care task force published guidelines which included annual wellness examinations and laboratory screening for middle-aged pets and twice-yearly screening for senior pets. In addition, a critical component of the guidelines as well as those of the 2008 American Association of Feline Practitioners (www.catvets.com) senior care guidelines is the questioning of pet owners to determine if any changes have occurred in their pet’s health or behavior. Often the signs are mild or subtle and not necessarily a concern for the owners. In addition, if veterinarians do not educate owners that these signs might be indicative of emerging health and welfare concerns and that many of these problems can be resolved or improved if diagnosed early, the owners will not know the importance of reporting these signs. One practical and efficient way to ensure that signs are identified and recorded is to develop or utilize a questionnaire that the owner can complete at each visit and that is kept in the medical record for future comparison (Form 13.1). A separate and more detailed cognitive questionnaire might also be utilized to record and track behavioral signs for pets in which changes have already been identified (Form 13.2).

Form 13.2

Cognitive dysfunction screening checklist (client form #4, printable version available online)

| Pet’s name: | Age: | Today’s date: |

|---|---|---|

| Key: 0 – none; 1 – mild; 2 – moderate; 3 – severe | Age first noticed | Score |

| Confusion – awareness – spatial orientation | ||

| Gets stuck or can’t get around objects | ||

| Stares blankly at walls or floor | ||

| Can’t find / leaves dropped food | ||

| Goes into wrong side of door; walks into door / walls | ||

| Relationships – social interactions | ||

| Decreased interest in petting / avoids contact | ||

| Decreased greeting behavior | ||

| In need of constant contact, overdependent, “clingy” | ||

| Altered relationship with other household pets – less social | ||

| Altered relationship with other household pets – fear / anxiety | ||

| Aggression -to family members __________________; -to unfamiliar people_________________ -to family pets_________________; unfamiliar pets ________________ -Other:__________________________________________________ | ||

| Response to stimuli | ||

| Decreased response to auditory stimuli (sounds) | ||

| Increased response, fear, phobia to auditory stimuli | ||

| Decreased response to visual stimuli (sights) | ||

| Increased response, fear, phobia to visual stimuli | ||

| Decreased responsiveness to food / odor | ||

| Activity / anxiety – increased/repetitive | ||

| Pacing / wanders aimlessly | ||

| Snaps at air / licks air | ||

| Licking owners _________, household objects _________ | ||

| Vocalization | ||

| Increased appetite (eats quicker or more food) | ||

| Restless / agitation | ||

| Activity – apathy / depressed | ||

| Decreased interest in food / treats | ||

| Decreased exploration / activity | ||

| Decreased interest in social interactions / play | ||

| Decreased self-care | ||

| Sleep–wake cycles; reversed day/night schedule | ||

| Restless sleep/waking at nights | ||

| Increased daytime sleep | ||

| Learning and memory – housesoiling | ||

| Indoor elimination at sites previously trained | ||

| Decrease/loss of signaling | ||

| Goes outdoors, then returns indoors and eliminates | ||

| Elimination in crate or sleeping area | ||

| Incontinence | ||

| Learning and memory – work, tasks, commands | ||

| Impaired working ability/decreased ability to perform learned task | ||

| Decreased responsiveness to commands and tricks | ||

| Inability/slow to learn new tasks (retrain) | ||

| Decreased recognition of familiar people / pets |

It is clear from the publication of numerous prevalence studies that owners do not voluntarily report many of these behavioral changes. In one study owners of dogs aged 11–16 that had no health or behavioral abnormalities noted on their medical records during the annual visit were called to inquire retrospectively if there were any noticeable behavioral changes. Twenty-eight percent of 11–12 year-old dogs and 68% of 15–16-year-old dogs had at least one sign of DISHA.5 In another study, CDS was diagnosed in 14 dogs that had visited the veterinarian for a routine annual check-up and reported no behavioral complaints until actively questioned by the veterinarian.6 In an Italian study, 124 dogs over 7 years of age were evaluated and, after eliminating 22 with medical causes, 41% had alterations in one category and 32% had signs in two or more categories; therefore at least 73% had signs.7 In another study, the prevalence of CDS in 325 dogs over 9 years of age was 22.5%.8 Social interactions and housesoiling were the most commonly reported signs. Females and neutered males were significantly more affected than intact males. One previous study also identified a trend toward a higher prevalence in neutered males.9 A recent study based on a large internet survey reported a prevalence of 5% in dogs 10–12 to 23.3% in dogs 12–14 and 41% in dogs over 14, with an overall prevalence of 14.2%.2 Once clinical signs are identified, the prevalence and severity of signs increase with age.2,8,10 Studies of behavior signs in aged cats are lacking. However, in one study of 154 owners of cats aged 11 and older, after eliminating 19 cats with medical problems, 35% of the cats were diagnosed with CDS – 28% of 95 cats aged 11–15, and 50% of 46 cats over 15 years.11 In addition, estimates of the prevalence of CDS in dogs and cats are likely greatly underestimated since deficits in learning and memory likely arise several years before the first clinical signs of cognitive decline appear (discussed below).

It is therefore the role of the veterinarian and staff to inform and educate clients of the importance of reporting these signs. Handouts and web links can be used to educate owners further about geriatric care and questionnaires can be used to screen for problems quickly and extensively at each visit (Forms 13.1 and 13.2).

Causes of senior pet behavior problems

Medical causes

Medical differentials for behavior problems are discussed in detail in Chapter 6 (see Table 6.1). However, the practitioner should focus on disease processes that are most likely to affect senior pets. The aging process is associated with progressive and irreversible changes that can affect behavior. In fact, any disease that affects the central nervous system (CNS: including hepatic encephalopathy, tumors, CDS) or its circulation (e.g., cardiac disease, anemia, hypertension) can affect behavior.

If medical problems are diagnosed, it can be a challenge to determine whether the problem is actually causing the behavioral signs. Response to therapy may therefore be an important step in the workup (see Chapter 6 for details). Unfortunately, with age not all medical problems can be resolved or improved and some may continue to progress. Therefore, the owner should be provided with realistic expectations and modifications may be required to the pet’s environment or schedule to help the family and pet best manage the situation.

The role of stress in health and behavior

As discussed in Chapter 6, stress can contribute to both health (e.g., dermatologic, gastrointestinal, aging) and behavioral problems (e.g., anxiety, compulsive disorders). Stress is an altered state of homeostasis which can be caused by physical or emotional factors. In the aging pet, there is a general deterioration in physical condition, tissue hypoxia, alterations in cell membranes, increased production and decreased clearance of reactive oxygen species, a decline in organ, sensory, and mental function, a gradual deterioration of the immune system, and decreased ability to cope with change. Thus, the senior pet in particular is less able to respond to stress and maintain homeostatic balance. Owners should be encouraged to maintain a stable and predictable environment and schedule; to plan and make any necessary changes gradually; and to monitor pet enrichment programs, especially for cats (see below) to ensure that they have a positive and desired effect.

Cognitive dysfunction and brain aging

Cognitive dysfunction syndrome

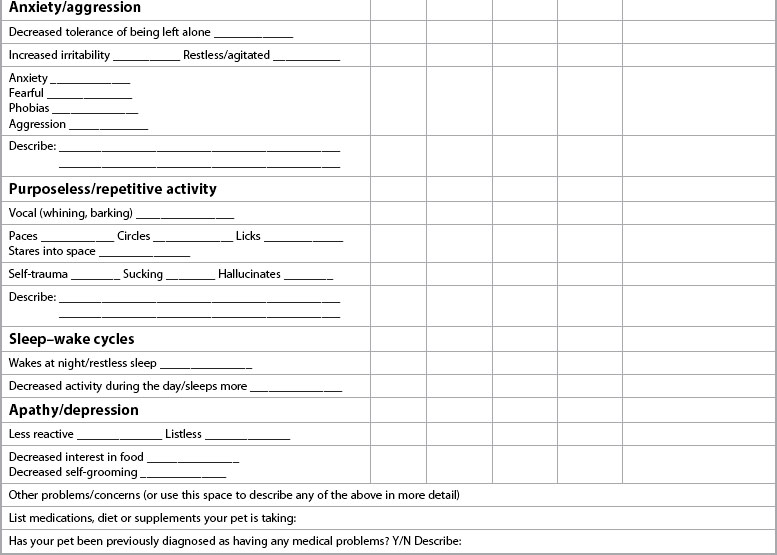

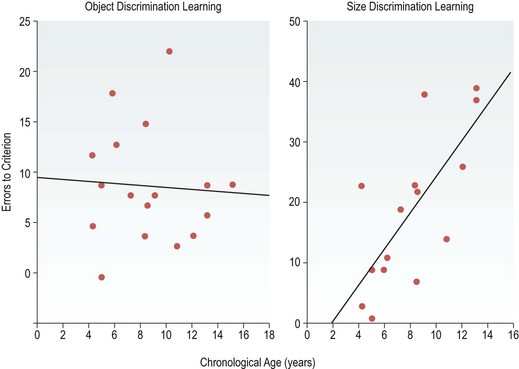

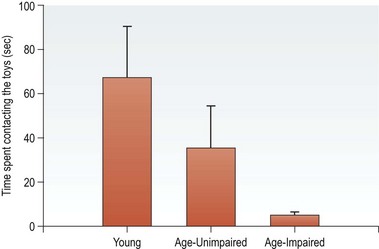

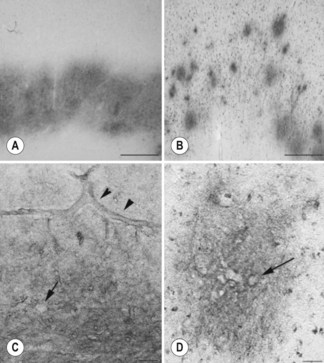

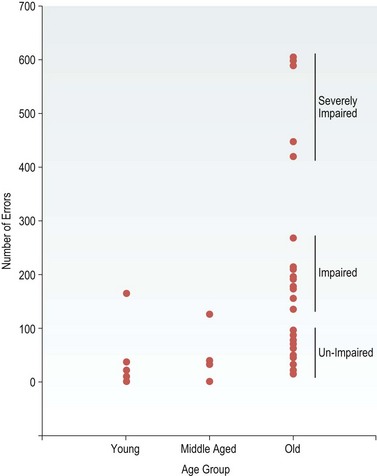

CDS is a neurodegenerative disorder of senior dogs and cats that is characterized by increasing brain pathology and gradual cognitive decline.1,12–19 The development and validation of tests for assessing cognitive function in dogs, including discrimination, oddity, reversal, attention, and spatial memory, have been instrumental in documenting tasks on which senior and old dogs cannot succeed as well as adult dogs1,17,18,20,21 (Figures 13.1 and 13.2); cats can be tested as well (Figure 13.3). For example, visual discrimination learning (learning which of two objects covers a reward) is not usually affected by age in most animals, including dogs. However, if the task is more difficult, such as in size discrimination (i.e., the dog must learn whether a small or large object covers the food; Figure 13.4), aged animals have more difficulty in learning the task compared with younger animals. Tasks requiring the inhibition of a previously learned behavior, as in reversal learning (the dog must learn that the food is now under the opposite object), are also sensitive to age.18 This may be due to the fact that reversal learning but not discrimination learning in dogs requires the intact function of the prefrontal cortex. This is a brain region in dogs in which the earliest and most consistent neuropathology tends to arise. Memory decline in dogs is also age-dependent. Using memory tasks, such as where the dog is required to recall which object covered the food after gradually longer delays, some aged dogs are unable to remember the location of an object seen 5–10 seconds previously.22 Memory testing reveals three groups of aged dogs: (1) unimpaired; (2) impaired; and (3) severely impaired (Figure 13.5). This is consistent with the findings in the geriatric human population. Laboratory studies have identified altered sleep–wake cycles, increased stereotypy, decreased social contact with humans, and a decreased interest in exploration and play with toys in dogs with cognitive impairment23 (Figure 13.6).

Figure 13.3 Feline testing. Cat being tested on two-choice memory task (delayed nonmatching to position position: DNMP).

(Courtesy of CanCog Technologies.)

Figure 13.5 Spatial memory is unimpaired, impaired, or severely impaired in three different subsets of aged dogs.

(Reproduced from Head E, Milgram NW, Cotman CW. Neurobiological models of aging in the dog and other vertebrate species. In: Hof AP, Mobbs C (eds) Functional neurobiology of aging. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 2001, pp. 457–468, with permission from Academic Press.)

To date, similar laboratory models in cats have been inconsistent. In one study, deficits in eye blink conditioning, found in Alzheimer’s patients, were also demonstrated in a subset of aged cats.24 In a second study, evaluating performance on a hole board task, aging did not appear to affect spatial learning but working memory errors were identified.25 Recently CanCog Technologies (www.cancog.com) has modified the canine test apparatus and protocols for use in cats. Preliminary data demonstrated age differences, with senior cats being impaired relative to normal adults.26 This feline battery should be instrumental in determining the relationship between brain pathology and CDS in cats as well as in the development of therapeutic interventions.

Based on clinical signs alone, CDS has been traditionally diagnosed in dogs at 11 years and older. However, dogs show impairment in the spatial memory task as early as 6–8 years of age.19 These functions are highly dependent on the frontal lobe, which shows atrophy and beta-amyloid accumulation prior to other brain areas.14 In cats, cognitive and motor performance appears to decline starting at approximately 10–11 years of age, but functional change in the neurons of the caudate nucleus has been seen as early as 6–7 years.25,27,28

Clinical signs and diagnosis of cognitive dysfunction syndrome

To diagnose CDS, veterinarians must rely on owner history. Only with careful questioning is it likely that signs would be detectable in the earliest stages of development. The diagnosis was initially based on clinical signs represented by the acronym DISH, representing disorientation, altered interactions with people or other pets, altered sleep–wake cycles, and housesoiling. In addition, since activity may initially decline and over time become restless or repetitive in pets with CDS, an A for activity has been added (DISHA). However, one of the earliest signs of CDS, a decline in memory and learning, which is the primary measure for early detection of human Alzheimer’s, is unlikely to be identified by pet owners in the absence of laboratory testing, except perhaps for those pets that are trained to a higher level of performance. On the other hand, the additional mental enrichment these working pets receive might theoretically slow the decline (see treatment of cognitive dysfunction, below). In addition, based on owner-reported behavior concerns in senior pets, anxiety appears to be associated with brain aging and cognitive decline in dogs and cats and this is analogous to the anxiety, troubled sleep, and agitation often associated with diseases causing cognitive decline and frontal-lobe dysfunction in humans29,30 (Box 13.1).

Box 13.1

Signs of cognitive dysfunction syndrome

• Altered relationships and social interactions

• Changes in activity: increased anxiety, pacing, repetitive behaviors (vocalizing, pacing)

• Changes in activity: apathy, depression

• Altered sleep–wake cycles; reversed day/night schedule

• Learning and memory problems: housesoiling

• Learning and memory problems: deficits in work, tasks, and commands

Standardized scales for screening and diagnosing cognitive dysfunction are still under development. One screening tool (Figure 13.4) offers a method for veterinarians to assess whether any of the signs have developed since the previous visit. This should immediately prompt further questions to determine if there are any other concurrent signs that might be consistent with an underlying medical problem, a comprehensive medical evaluation, and a behavioral history to rule out any changes in the pet’s schedule or household that may have caused or contributed to the signs (Box 13.2). If a diagnosis of cognitive dysfunction is made, the role of diet, enrichment, supplements, and drugs can be discussed and a therapeutic response trial initiated. Alternately, if signs are subtle, reassessment should be scheduled in 6 months since cognitive dysfunction is likely to progress in the number, frequency, or intensity of signs over 6–12 months.2,8,10 Other scales that have been developed to measure cognitive dysfunction are the 13-trait scoring system developed by Salvin et al, and the Age-Related Cognitive and Affective Disorder (ARCAD) scale developed in France31 (see Chapter 22).

Box 13.2

Components of the diagnostic workup for senior pets with behavioral signs

1. Medical history to determine if there are any concurrent medical signs

2. Evaluate drugs, supplements (including over-the-counter products) and diet that might affect behavior

3. Physical examination, palpation for signs of pain, evaluation of gait and mobility

4. Neurological examination, sensory evaluation and, if indicated, additional tests including ophthalmic exam, brainstem auditory evoked response, and brain imaging (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging)

5. Laboratory tests, including complete blood count, biochemical profile, and urinalysis; blood pressure where indicated

6. Viral testing (e.g., feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukemia virus) and endocrine function testing where indicated (e.g., thyroid, adrenal)

7. Behavioral history to determine if any environmental changes may have incited the signs

Aging and its effect on the brain

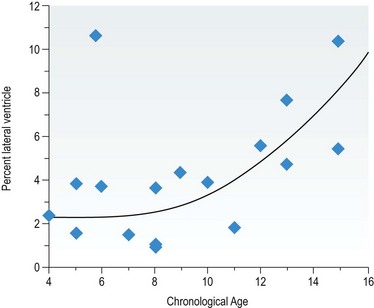

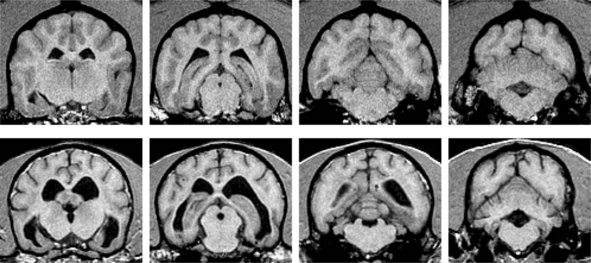

In dogs, advancing age is associated with frontal volume decreases and ventricular size increases and there is evidence of meningeal calcification, demyelination, increased lipofuscin and apoptotic bodies, neuroaxonal degeneration, and a reduction in neurons15,16 (Figure 13.7). Using magnetic resonance spectroscopy, preliminary studies have demonstrated an age-related decline in markers of neuronal health in both dogs and cats32,33 (Figure 13.8). There is also evidence of age-associated brain pathology in cats, including neuronal loss, increased ventricular size, cerebral atrophy, and widening of the sulci, although perhaps not as marked as seen in dogs.11,34,35 Perivascular changes, including microhemorrhage or infarcts in periventricular vessels, have been reported in senior dogs and cats. Arteriosclerosis of the nonlipid variety may also be seen in the older dog and cat as a result of fibrosis of vessel walls, endothelial proliferation, mineralization, and beta-amyloid deposition. This angiopathy may compromise cerebrovascular blood flow, which may be responsible for some of the signs of cognitive dysfunction.11–16,36

Functional changes that may occur in the aging brain include a possible depletion of catecholamines and an increase in monoamine oxidase B (MAOB) activity in dogs.37 A decline in the cholinergic system function has also been identified in dogs and cats, and this may contribute to cognitive decline and possibly motor function, as well as alterations in rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep.34,38–41 In dogs, cats, and humans there is an accumulation of diffuse beta-amyloid plaques and perivascular infiltrates which increases with age.11–14 Beta-amyloid can be detected as early as 7 years of age in dogs and 10 years in cats, and both the quantity and frequency of distribution increase with age.42 In both dogs and cats, the deposits appear in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, and in the meningeal vessel walls of dogs, but not cats. Dogs display strikingly similar Aβ pathology to that seen in Alzheimer’s patients.12,43 Furthermore, increased Aβ plaques are positively correlated with cognitive impairment in dogs13,14,43 (Figure 13.9). Genetics may be a contributing factor in the extent of amyloid distribution, as some breeds develop beta-amyloid at an earlier age and there is high concordance within litters in the extent of beta-amyloid.44 Diffuse Aβ plaques and perivascular infiltrates are also present in the brains of cats 10 years and older and have been reported to appear in cats as young as 7.5 years of age.45 Compared to humans and dogs, plaques are more diffuse, although senile plaques that are morphologically similar to dogs have been reported.12,36,42,46,47 However, the link between CDS and Aβ pathology in the cat is inconsistent, as some studies demonstrated a positive link,12,46 while others show no correlation.47 The most striking difference from humans is the absence of neurofibrillary tangles in dogs and cats, although hyperphosphorylated tau is reported and may represent pre-tangle pathology.11,46,48,49

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree