8 The dysphagic/gagging/regurgitating cancer patient

Dysphagia is defined as painful or difficult swallowing and can usually be subclassified as oral dysphagia, pharyngeal dysphagia and cricopharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia, therefore, generally refers to pathology within the oral cavity and/or the pharyngeal region. Gagging is defined as the reflex part of swallowing/vomiting, involving elevation of the soft palate followed by reverse peristalsis of the upper gastrointestinal tract and it is often accompanied by retching, which is the involuntary and ineffective attempt to vomit. Regurgitation is defined as the passive, retrograde expulsion of gastric or oesophageal contents and as such is a sign of oesophageal disease. Cancer patients with some or all of these clinical signs therefore could have neoplastic disease in one or more than one of several locations:

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 8.1 – TONSILLAR CARCINOMA IN A DOG

Case history

Diagnostic evaluation

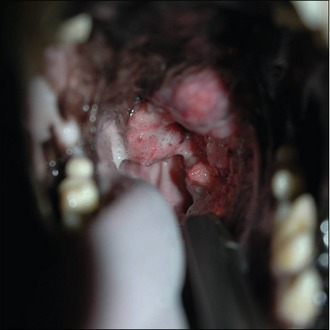

In this particular case, as the dog would not allow a thorough oral examination, it was decided to undertake a more detailed evaluation under sedation. Careful oro-pharyngeal examination revealed the presence of an ulcerated mass lesion originating in the region of the left tonsil but extending dorsally and enlarging over the palatine region to the right tonsillar crypt (Fig. 8.1).

Further evaluation

The dog was anaesthetized and inflated thoracic radiographs were obtained. These revealed no metastatic lesions. The lesion was then biopsied with rigid grab forceps and haemostasis was achieved by direct pressure using sterile swabs. Prior to biopsy the laryngeal area was packed with a swab bandage to absorb any excessive haemorrhage. The swelling in the retropharyngeal region was assessed by ultrasound. This revealed two large, homogeneous structures consistent in appearance with the retropharyngeal lymph nodes. Fine needle aspirates of these were obtained for cytology.

Theory refresher

Tonsillar carcinomas are usually seen in older dogs (mean age 10 years in one study, range 2–17) and are considered highly metastatic tumours, with 10–20% having pulmonary metastasis identified at initial presentation and 77% having distant metastasis identified on post-mortem. No specific breeds have been identified as having a particular predisposition to this disease but some studies have reported a significantly higher incidence of the condition in dogs living in urban environments compared to rural locations. Tonsillar carcinomas display rapid growth, significant invasion into surrounding tissues and early metastasis to regional lymph nodes and then lungs and/or other distant organs. Treatment therefore is difficult, as although tonsillectomy may help to alleviate the presenting clinical signs in the short term (and such a procedure may also be required to achieve a definitive diagnosis), it can never be considered to be a procedure undertaken with curative intent. The efficacy of tonsillectomy with postoperative radiotherapy has been studied and this approach does appear to offer better control of local spread and increases the average survival times compared to surgery alone. But the 1-year survival rates are still very low at 10% and the mean survival time reported in one study was only 151 days. Sole-agent chemotherapy does not appear to have any reasonable activity against tonsillar carcinomas. In one study, various chemotherapy combination treatments were assessed and the mean survival times were only approximately 100 days despite treatment. Combining external beam radiation therapy with chemotherapy (doxorubicin and cisplatin) does appear to generate significantly longer survival times (mean 306 days) but disease progression and the development of distant metastasis is still the major obstacle to longer-term survival times. Currently therefore, the treatment associated with the longest life expectancy for patients with carcinoma of the tonsil would be surgical excision followed by combination radiation and chemotherapy. However, in many cases, advising that no further treatment would be fair for the animal is certainly acceptable if the disease is extensive and the primary tumour is causing significant clinical problems.