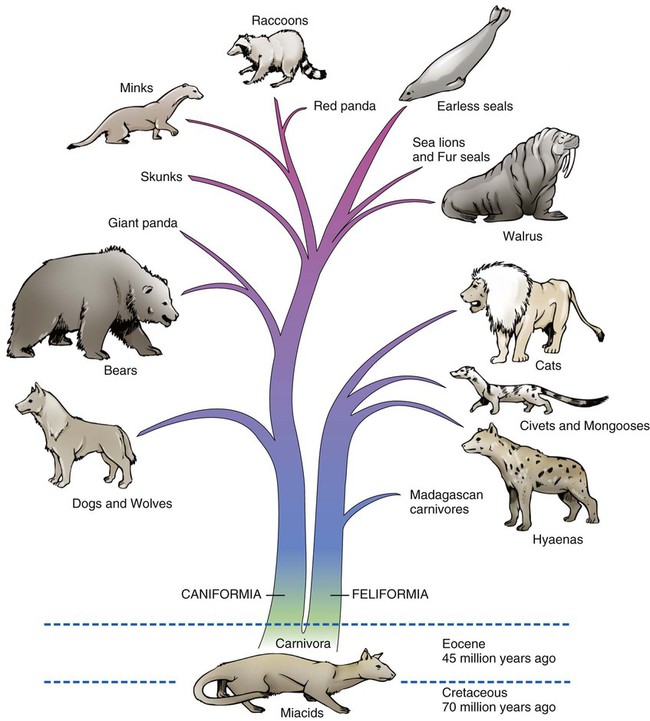

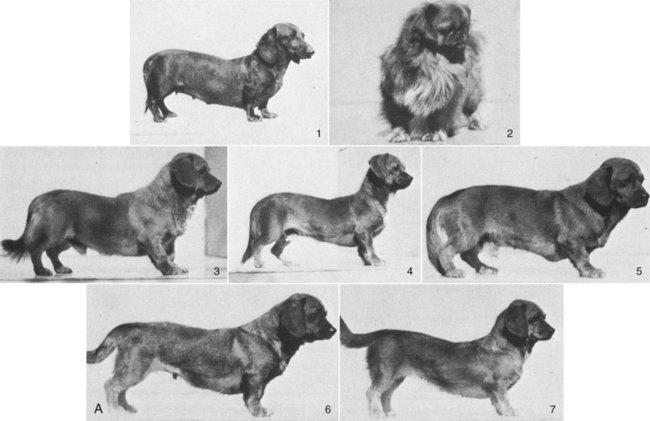

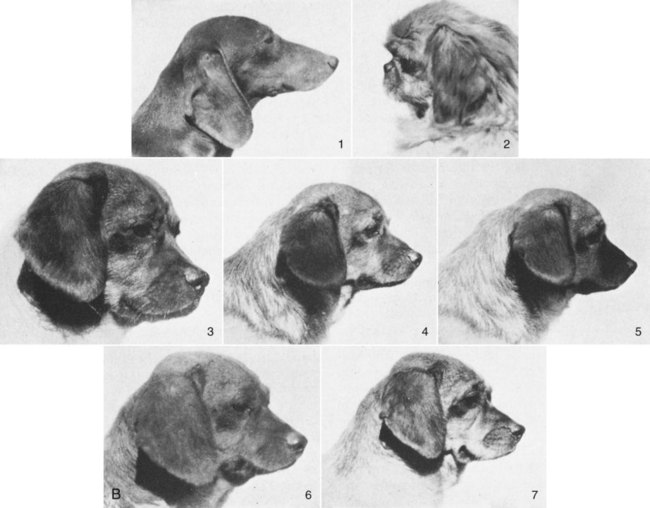

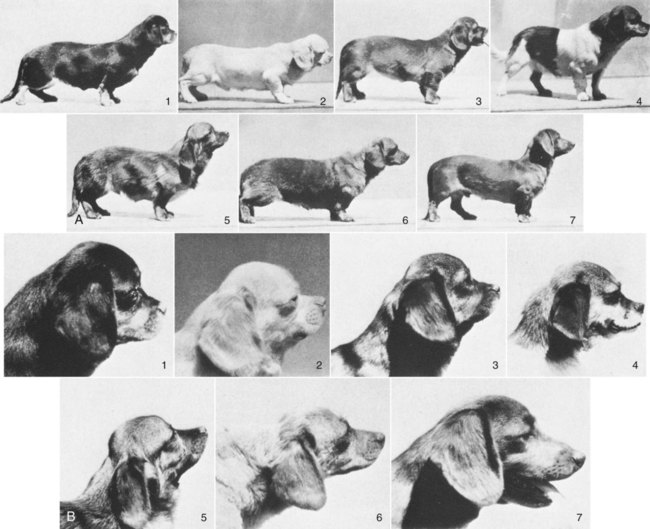

This text is based on anatomic studies of many dogs of diverse and usually unknown ancestry commonly referred to as mongrels. Domestic dogs are probably the most polymorphic mammals referred to as a single species, Canis familiaris, and some workers have suggested that no domestic animal be given species designation (Groves, 1971). The alternatives are the use of subspecific names or breed designations. Because all members of the family Canidae are interfertile and human interaction has affected their hybridization and distribution throughout the world, it appears simplest to adopt one term for all purebreds, mongrels, and feral dogs. For historical considerations of the world’s wild and domestic dogs see Smith (1845-1846) Mammalia: Dogs, Vol. I & II (with color plates), in The Naturalist’s Library, Vol.18, by W. Jardine; Darwin (1868), Animals and Plants under Domestication, Ash (1927); Fiennes and Fiennes (1968); Titcomb (1969); Epstein (1971); American Kennel Club (AKC) The Complete Dog Book (2006); and Fogle and Morgan (2009) Encyclopedia of the Dog, which covers 420 breeds. The order Carnivora is worldwide in distribution and is an assemblage of intelligent, mostly flesh-eating mammals with prominent canine teeth; molars adapted for crushing, cutting, and grinding; and a relatively short alimentary canal. Members of the order have digits provided with claws and sometimes with webs. Behavioral characteristics identify most of them as predators with strong family ties, devoted to the care of their young. Many of the species adapt readily to domestication (Clutton-Brock & Jewell, 1993; Ewer, 1973). Wayne and Ostrander (2007) have investigated the dog genome sequence and associated genomic resources and said that these studies “will revolutionize the study of dog evolution, population structure and genetics.” They presented a chart of canid relationships that shows the major groupings of species. A more accurate phylogeny of the Dog family, Canidae, is in the making and molecular markers that identify gene pools now allow the assignment of mixed “breeds” to specific gene pools. The WISDOM Panel MX of Mars Veterinary, Inc., has a deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)–based test that can identify 134 American Kennel Club (AKC)–registered breeds that may be present in a mixed breed dog (Giger et al., 2007). The most complete treatment of fossil and living families and genera of mammals can be found in Classification of Mammals above the Species Level, by Malcolm McKenna and Susan Bell (1997) with contributions from George G. Simpson. This classification project was begun by Simpson (1945) in 1927 at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Many people cooperated in assembling this tome, which includes all mammals of the world. The number of extinct taxa is much greater than living forms and many fossil animals are known only from a few bones or teeth. In a more recent compilation of species, Wozencraft (2005) revised the Order Carnivora in Wilson and Reeder (2005) Mammalian Species of the World. He raised the Giant Panda, the Madagascan Carnivores, the African Palm Civet, the Skunks, and the Walrus each to family rank. This pictorial family tree (Fig. 1-1) is an approximation of how animals in the Order Carnivora are related to each other according to the most recent classification. The major divisions are the Feliformia (cats) and the Caniformia (dogs), which may have arisen from Miacid stock between the Eocene and the Paleocene approximately 40 to 60 million years ago. This time frame witnessed the evolution of modern mammals and birds. Every year new fossils are found (as well as extant forms) and we are able to improve our understanding of animal phylogeny. For photographs of various mammals see Nowak (1991). Lion, Leopard, Snow Leopard, Cheetah, Tiger, Lynx, Bobcat, Domestic Cat, Marble Cat, Flat-Headed Cat, Golden Cat, Black-Footed Cat, Roaring Cats, Caracal, Ocelot, Puma, Jaguarundi, Serval, Jaguar, Eyra Mongooses, Ichneumon, Cusimanses Oriental Civet, Genets, African Civet, Palm Civets, Water Civet, Linsangs, Binturong, Bornean Mongoose, Suricate, Meerkat Fanaloka, Fossa (Madagascan Carnivores) Dogs, Wolves, Coyote, Foxes, Dhole, African Hunting Dog, Culpeo, Guara, Crab-Eating Fox, Raccoon Dog, Dingo, Bush Dog, Jackals, Dire Wolf Eared Seals, Fur Seals, Sea Lions Harbor Seal, Ringed Seal, Ribbon Seal, Harp Seal, Hair Seals, Earless Seal, Bearded Seal, Gray Seal, Hooded Seal, Elephant Seal, Monk Seal, Ross Seal, Leopard Seal, Weddell Seal Minks, Otters, Stink Badger, Marten, Sable, Fisher, Pine Marten, Weasels, Stoat, Ferret, Polecat, Badgers, Grison, Zorille, Taira, Ratel, Wolverine Ring-Tailed Cat, Olingo, Kinkajou, Coatis, Raccoon, Lesser Red Panda The family Canidae is a distinct group of dog- and foxlike animals distributed throughout the world (Gittleman, 1989; Mivart, 1890; Sheldon, 1992). Although there is general agreement about which genera are included in the family, there has been disagreement about the generic status of several species and their groupings into subfamilies. Clutton-Brock et al. (1976) reviewed the family Canidae using numeric methods and suggested a classification at the generic level based on 90 characters of the skeleton, pelage, internal anatomy, and behavior. Their results indicated that the three largest genera—Canis (dog, wolf, coyote, jackal), Vulpes (foxes), and Dusicyon (South American foxes and foxlike animals)—all are closely related but merit the separate designations they now have. Wayne (1993) and Wayne and colleagues (1989, 1999, 2007) have investigated the evolutionary relationships of carnivores using karyologic and molecular procedures. Their techniques, such as DNA hybridization, protein electrophoresis, albumin immunologic distance, and high-resolution G-banding of karyotypes, have helped define relationships. Our current understanding of the taxonomy of carnivores and dogs, in particular, is discussed by Wayne and Ostrander (2007) and Boyko et al (2010). Behavior is a feature that is sometimes characteristic of a breed. Takeuchi and Mori (2006) compared the behavior of purebred dogs in Japan with those in the United States and the United Kingdom. Stockard (1941) also took note of behavior in the purebred crosses he was producing. Because all dogs are interfertile, many intermediate physiognomies are not assignable to any particular breed (Stockard, 1941; Van Gelder, 1977). Even first-generation hybrids of purebred parents may exhibit bizarre combinations of body characteristics (Figs. 1-2 and 1-3). Charles R. Stockard of the Cornell Medical College undertook an investigation, starting about 1926, of the genetic and endocrinic basis for differences in form and behavior in dogs. He made crosses between many purebred dogs of various breeds and their F1 and F2 generations to study the physiognomy, skeleton, and endocrine organs of the resulting litters. Unfortunately, like Malcolm E. Miller, who started “Anatomy of the Dog,” Stockard died before his work was completed, but from his extensive notes, photographs, and specimens his colleagues were able to publish many of his findings as a monograph of the Wistar Institute (Stockard, 1941). What remains of the records and the extensive skeletal collection is now housed and cataloged in the Museum of Natural History on the campus of the University of Georgia in Athens and can be examined by appointment. Stockard’s monumental study has left a legacy of numerical comparisons of body and skeletal parts, documented photographs of parents and hybrids, and many disarticulated skeletons. The purebred crosses he produced raise many questions as to the interactions of a large number of breed factors on external features and deformations of the skeleton. Dachshund-Pekingese hybrids are good examples of genetic influences on variations in skull form (see Figs. 1-2 and 1-3). The Pekingese dog has a greatly reduced muzzle and a bulging forehead. This is probably a result of achondroplasia of the basicranium and the cartilaginous forerunner of the upper jaws, a condition similar to that seen in the Bulldog. The Asiatic origin of the Pekingese suggests descent from Chow-Chow ancestors, whereas the Bulldog was developed at a later date from European stock. Thus very different breeds of dog can have very similar mutations in various parts of the world, and, if selected, these mutations can be enhanced.

The Dog and Its Relatives

The Order Carnivora

The Family Canidae

Hybrids

B, Close-up of the facial features of a Dachshund bitch and a Pekingese stud compared with the same first-generation hybrids as shown in Figure 1-2A. Of the 22 F1 hybrids produced by several bitches, all were uniform in size and type irrespective of whether they were whelped from Dachshund or Pekingese dams. The hybrids were larger and more vigorous than either parent stock. (From Stockard CR, Johnson AL: The contrasted patterns and modifications of head types and forms in the pure breeds of dogs and their hybrids as the result of genetic and endocrinic reactions. In CR Stockard, editor: The genetic and endocrinic basis for differences in form and behavior: American anatomical memoirs, vol 19, Philadelphia, 1941, Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology.)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree