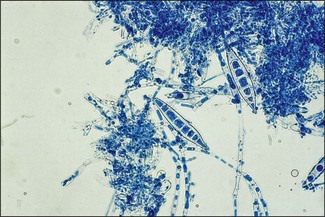

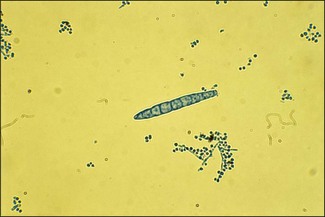

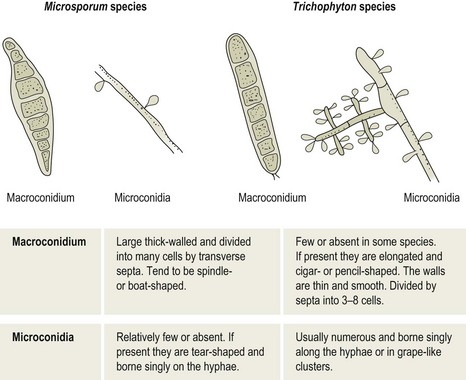

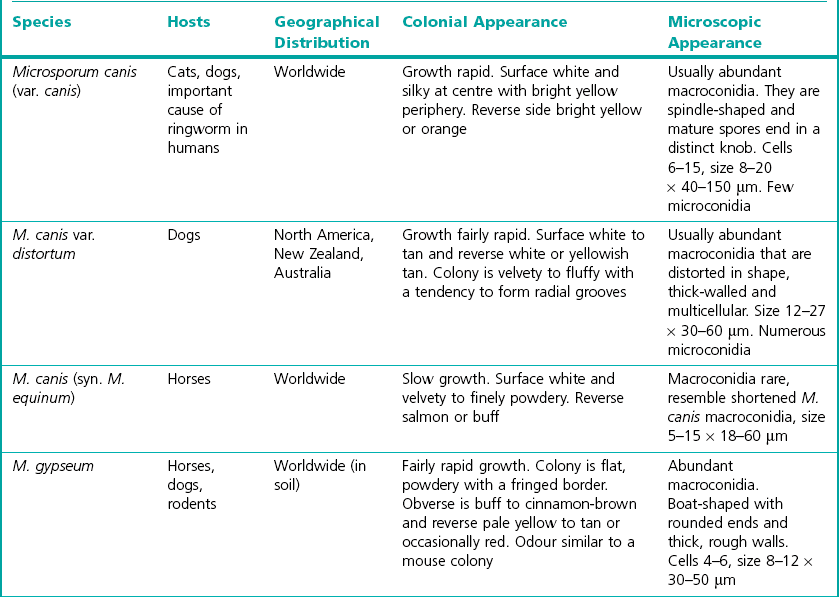

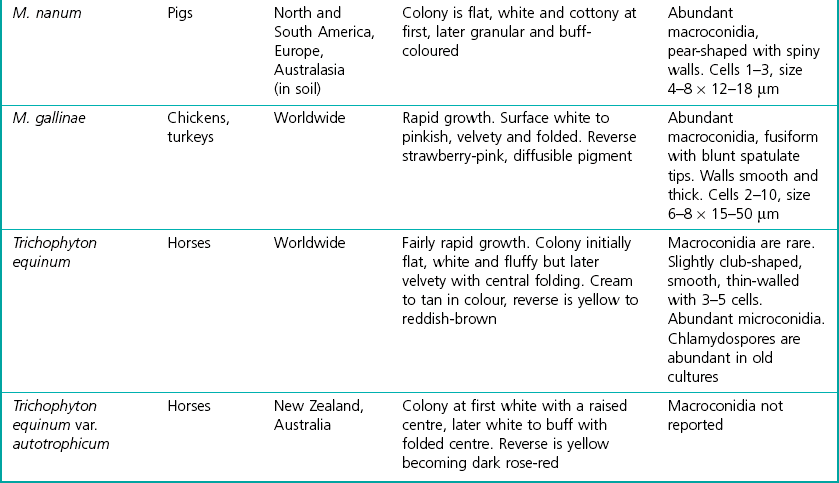

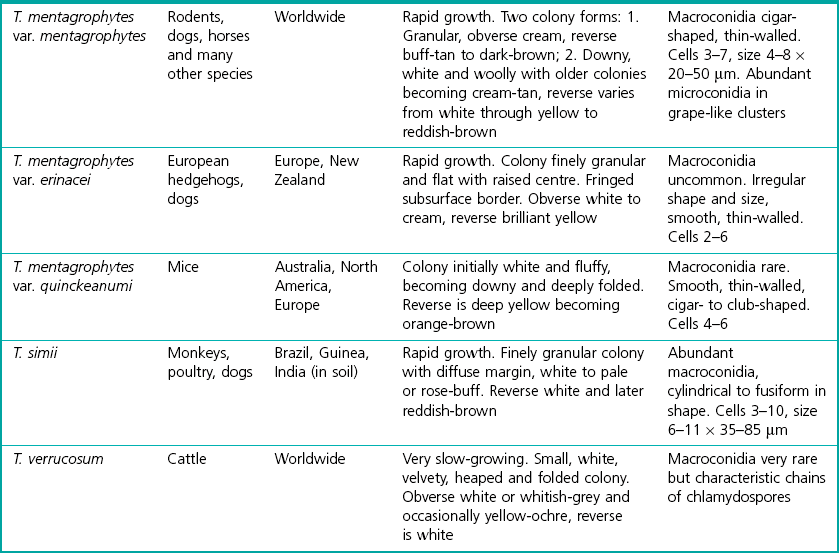

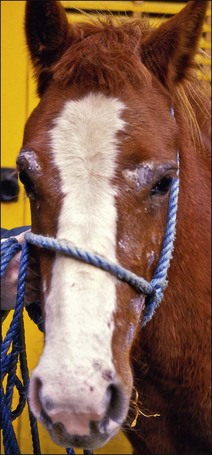

Chapter 38 Over 30 species of dermatophytes are known. Those affecting animals are placed in one of two genera, Microsporum or Trichophyton. Epidermophyton floccosum is principally a human pathogen. The dermatophyte species affecting animals are described as ectothrix as the septate hyphae invading the skin and hairs fragment into arthrospores and these form a sheath around the infected structures. Macroconidia and microconidia are produced in the non-parasitic state in laboratory cultures. The Microsporum species tend to produce spindle (Fig. 38.1) or boat-shaped (Fig. 38.2) macroconidia whereas those of the Trichophyton species are usually elongated, cigar-shaped with almost parallel sides (Fig. 38.3). The macroconidia of M. nanum are unique in being round and usually two-celled (Fig. 38.4). Figure 38.5 gives the main points of differentiation between the two genera. The colonies of many of the dermatophytes are pigmented and both the obverse and reverse of the colonies should be examined to assist identification. • Microsporum persicolor: voles • Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. erinacei: European hedgehogs • Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. mentagrophytes: rodents These dermatophytes generally give rise to subclinical or inapparent infections in the host animal, although they can also produce clinical lesions. Zoophilic species tend to be associated with a particular animal species. However, infection can also occur from reservoirs such as rodents (T. mentagrophytes), hedgehogs (T. erinacei; Fig. 38.6), soil (M. gypseum) and fomites such as bedding, grooming gear and harness containing hairs with infective arthrospores. Whilst growing on keratinized structures these fungi rarely produce macroconidia and rely instead on the production of arthrospores for transmission from host to host. Arthrospores can remain viable on shed hairs and skin particles for at least six to 12 months. The reservoir, transmission and site of the lesions can often be related to the actual dermatophyte involved. This is especially evident in the horse and the dog and is an argument in favour of attempting to isolate and identify the dermatophyte in an infection. Table 38.1 lists the main dermatophytes affecting animals, the main hosts of each and their geographical distribution. Infective arthrospores germinate within six hours of adhering to keratinized structures. Minor trauma of the skin and dampness may facilitate infection. The ability of the dermatophytes to hydrolyse keratin causes damage to the epidermis, hair shafts, hair follicles and feathers. The nature of the lesions is affected by the virulence of the fungus and the immunological response of the host. Very young and very old animals as well as debilitated or immunosuppressed individuals are most susceptible to infection. The host mounts an inflammatory response to the fungal metabolic products that is harmful to the fungus, so the dermatophyte moves away peripherally towards normal skin. The result is the commonly seen circular lesions (ringworm) of alopecia with healing at the centre and inflammation at the edge (Fig. 38.7). There appears to be a balanced host–parasite relationship where a dermatophyte has become adapted to a specific host animal. While these animals may not show lesions they can act as a reservoir of infection. The manifestations of dermatophyte infections can vary and may be summarized as: • Subclinical or inapparent infections • Classical round ringworm lesions • Serious generalized lesions that may be complicated by mange mites or by secondary bacterial infection, in particular by Staphylococcus aureus or S. pseudintermedius • Nodular or tumourous lesions called kerions, seen most commonly in dogs.

The dermatophytes

Natural Habitat

Pathogenesis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine