Chapter 53The Cervical Spine and Soft Tissues of the Neck

This chapter discusses disorders of the neck that may give rise to lameness or poor performance or result in an abnormal neck shape, abnormal neck posture at rest or while moving, or neck stiffness. Transient neurological conditions, conditions caused by trauma resulting in other injuries, and gait abnormalities that may be confused with lameness are considered, but those associated with compression of the cervical spinal cord are discussed in Chapter 60.

Clinical Examination

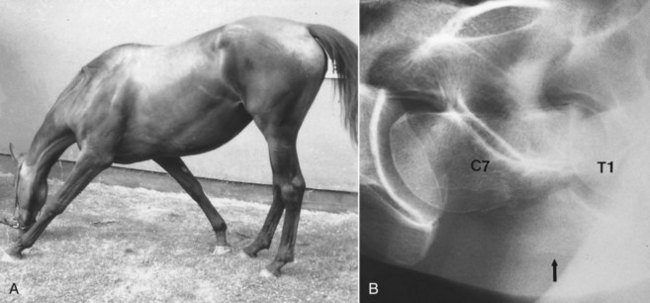

Neck flexibility should be assessed from side to side and up and down. This can be done by manually manipulating the neck, but many normal horses resist this. Holding a bowl of food by the horse’s shoulder to assess lateral flexibility is helpful. Ideally the horse should be positioned against a wall, so that the horse cannot swing its hindquarters away from the examiner during this assessment. The clinician should try to differentiate between the horse properly flexing the neck and twisting the head on the neck. Compare flexibility to the left and to the right. To assess extension of the neck, the veterinarian should evaluate the ease with which the horse can stretch to eat from above head height. Observing the horse grazing is helpful to assess ventral mobility of the neck. Especially with lesions in the caudal neck region a horse may have to straddle the forelimbs excessively to lower the head to the ground to graze (Figure 53-1, A). The horse should also be observed moving in small circles to the left and the right, and loose on the lunge.

Imaging Considerations

Radiography and Radiology

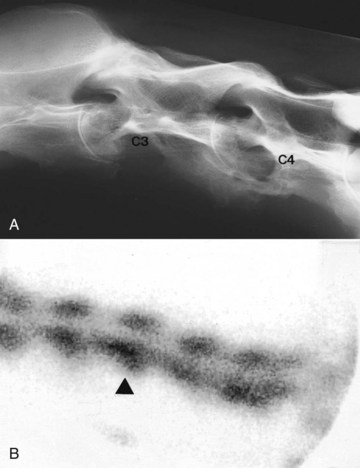

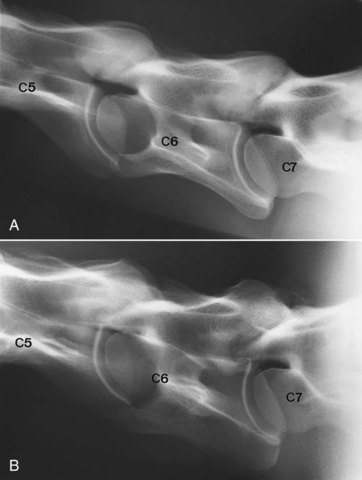

A number of variations of the normal radiological appearance of the cervical vertebrae should not be mistaken for lesions. A spur on the dorsocaudal aspect of the second cervical vertebra may project into the vertebral canal. The ventral processes of the sixth cervical vertebra and occasionally other vertebrae have small separate centers of ossification. The ventral lamina on the sixth cervical vertebra may be transposed onto the ventral aspect of the seventh cervical vertebra, unilaterally or bilaterally. The seventh cervical vertebra has a small spinous process, which may be superimposed over the synovial articulation between the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae and should not be confused with periarticular new bone. In older horses small spondylitic spurs may be seen on the ventral aspect of the vertebral bodies. Modeling of the dorsal synovial articulations between the fifth and sixth and between the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae is common in middle-aged and older horses3-5 (Figure 53-2).

Fig. 53-2 A, Lateral radiographic image of the caudal cervical vertebrae of normal 4-year-old Thoroughbred. The synovial articulations between the fifth (C5) and sixth (C6) cervical and sixth and seventh (C7) cervical vertebrae are outlined smoothly. The intervertebral foramina are distinct. Compare with part B and Figure 53-8. B, Lateral radiographic image of the caudal cervical vertebrae of 9-year-old clinically normal horse. The synovial articulations are enlarged between the fifth (C5) and sixth (C6) cervical vertebrae and particularly between the sixth and seventh (C7) cervical vertebrae.

Major radiological abnormalities such as fusion of two adjacent vertebrae can be present subclinically, in part because of the great mobility between adjacent vertebrae (Figure 53-3, A). The clinical significance of such lesions may also be determined by the athletic demands placed on the horse.

Nuclear Scintigraphy

Increased radiopharmaceutical uptake (IRU) is not necessarily synonymous with a lesion that is clinically significant; therefore images must be interpreted with care (see Figure 53-3, B). The clinician should compare images obtained from the left and right sides carefully, because disparity in radiopharmaceutical uptake may be clinically significant. The veterinarian should evaluate the actual conformation of the synovial articulations, because a change in shape even without IRU may be important. Fractures are not always associated with prominent IRU, and lesions may be missed in the caudal neck region because of the overlying muscle mass and the scapulae.

Thermography

Thermographic examination of the neck is discussed in detail elsewhere (see Chapters 25 and 95). However, I have found thermography of limited usefulness, except for identifying acute superficial muscle injuries.

Clinical Conditions

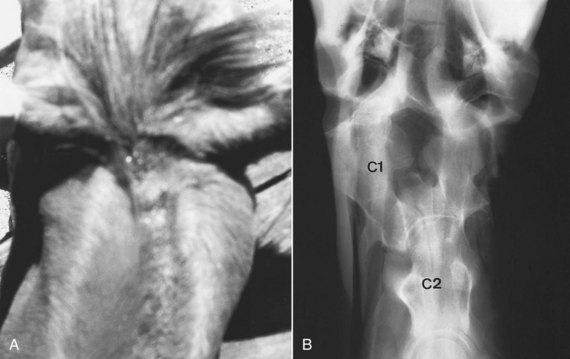

Occipito-Atlantoaxial Malformation

Occipito-atlantoaxial malformation (OAAM) is a congenital abnormality,13 and although it can occur in any breed,14 OAAM appears to be a heritable condition in Arabian horses15 (see Chapter 123). Clinical signs are usually recognizable within the first few weeks of life and include an abnormal neck shape in the poll region, with prominence on the left or right sides or both, and/or scoliosis (Figure 53-4, A). These signs are best appreciated when viewed from above. Usually no associated soft tissue swelling or pain exists, although an abnormal clicking sound may be audible because of subluxation of the atlantoaxial joint. The horse may have an abnormal limitation of movement in the poll region. The gait should be assessed carefully for neurological abnormalities; however, in many horses no neurological gait deficits are apparent.