Chapter 102The Bucked-Shin Complex

Etiology, Pathogenesis, and Conservative Management

Etiology, Pathogenesis, and Conservative Management

Conditions of fatigue failure of bone and inadequacy of bone modeling and remodeling of the third metacarpal bone (McIII) in the racehorse are part of a condition known as bucked shins or dorsal metacarpal disease.1,2 Bucked shins start in young healthy racehorses, usually Thoroughbreds (TBs) and Quarter Horses, but occasionally Standardbreds (STBs), that undergo intense training for racing, usually as 2-year-olds, while the skeleton is still immature and in the growth phase (Figure 102-1, A). The true incidence of bucked shins is unknown and may vary geographically, but reports range from 30% to 90%. A North American questionnaire cited an incidence of 70%.1 Stress fractures (dorsal cortical or saucer fractures) usually occur some months after initial signs of bucked shins and may be a potentially life-threatening injury if a horse is raced or exercised at speed (see Figure 102-1, B). The diagnosis of bucked shins is easy and often made by the trainer or owner. The history of sudden tenderness or soreness of the left McIII (in North America) or both the McIIIs after high-speed work or the first race, or soreness developing the day after, are cardinal signs of early bucked shins. Horses with severe disease manifest acute lameness and extreme sensitivity to palpation of the dorsal cortex of the McIII and are unwilling to train or race. All gradations of pain or disability may be seen. Swelling and tenderness may suggest new bone proliferation. Radiology is helpful to determine the amount of periosteal new bone formation, which determines prognosis. Large accumulations of periosteal new bone on the dorsal or dorsomedial surface of the McIII suggest a serious imbalance between exercise and bone fatigue and may portend actual stress fractures that will be seen on the dorsolateral aspect of the McIII some months later.

Research Findings

In Vitro Comparison of Local Fatigue Failure of the Third Metacarpal Bone

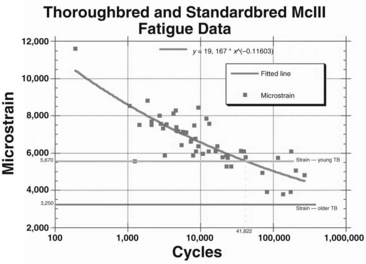

Data were analyzed using a power regression model for each horse and for each breed. Statistical differences were not found among the curves for individual horses of the same breed or for the curves between breeds. Pooled data then were used to describe fatigue characteristics of cortical specimens of the McIIIs from TBs and STBs of various ages, subjected fully to reversed cyclic loading (Figure 102-2).5 The bone from young horses was much more susceptible to fatigue failure.

In Vivo Strain Measurements: Relationship to Exercise

After acquiring in vivo strain data, we correlated these data with in vitro fatigue data previously generated by determining the average number of cycles that a young TB would gallop in training before the onset of bucked shins. The training records of six 2-year-old TBs that developed bucked shins were analyzed to determine the total distance worked before the onset of bucked shins. Stride length at canter, gallop, and racing speed was measured in a group of TBs to determine the number of strides (cycles) per mile. The total number of gait cycles was estimated based on the distances covered at a canter, at a gallop, and at work. The six horses were trained in these gaits for 10,000 to 12,000 cycles per month and developed bucked shins at 35,284 to 53,299 training cycles. These data were compared with the in vitro data described previously and showed good correlation (see Figure 102-2).

Relationship of Exercise to Bone Fatigue

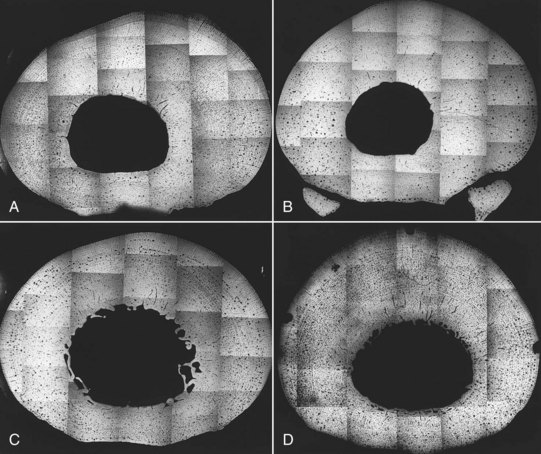

The classical training program consisted of daily gallops (approximately 18-second furlongs or 11.2 m/sec) of 1 to 2 miles per day (1.6 to 3.2 km), followed by shorter workouts or breezes at racing speed (approximately 14-second furlongs or 14.4 m/sec) once every 7 to 10 days that increased in distance from 2 to 6 furlongs (0.4 to 1.2 km) progressively over the course of the study. The modified classical training method used similar daily gallops, but the frequency of the high-speed workouts increased to three per week, and distances increased progressively from 1 to 4 furlongs (0.2 to 0.8 km). After 5 months the McIIIs were harvested from all horses. Microradiographs of bone sections were made to determine the extent of the remodeling activity (Figure 102-3). Bone modeling on the periosteal and endosteal surfaces of the McIII changed the cross-sectional geometry differently among the experimental groups. Classically trained horses (groups I and II) responded with appositional new bone formation on the dorsomedial periosteal surface, giving the impression that the medullary cavity, although reduced in diameter, was displaced laterally. Horses in the modified training group (group IV) had bone deposition dorsally and a slightly larger medullary cavity that was not displaced laterally. Control horses (group III) had new bone formation on the medial, lateral, and dorsal surfaces. The medullary cavity remained large and centrally placed. Examination of the McIII inertial properties showed that Imin in groups I, II, and III was similar, but the Imin of group IV horses was greater and was similar to the Imin previously reported for mature racehorses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree