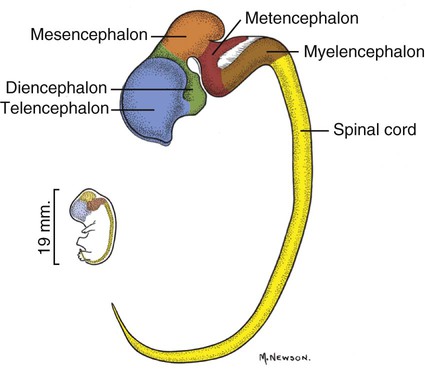

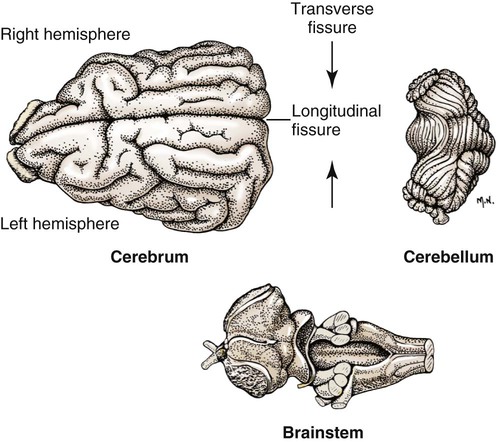

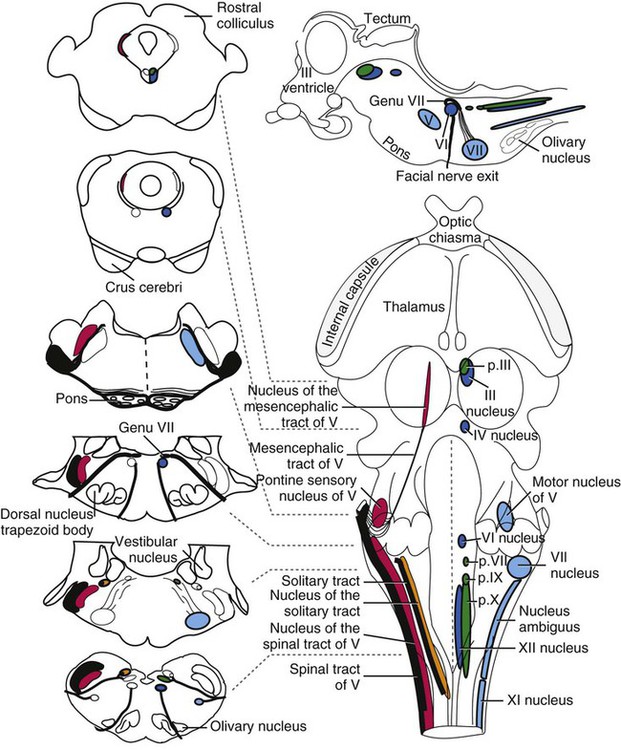

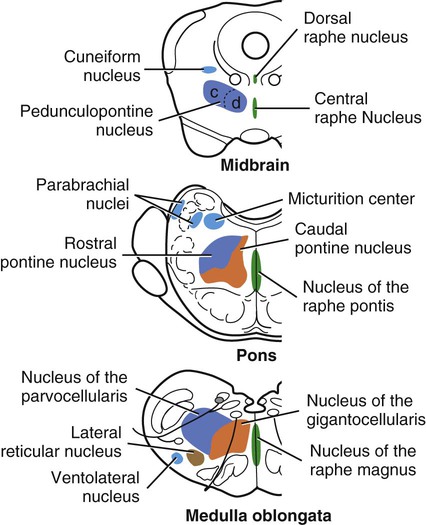

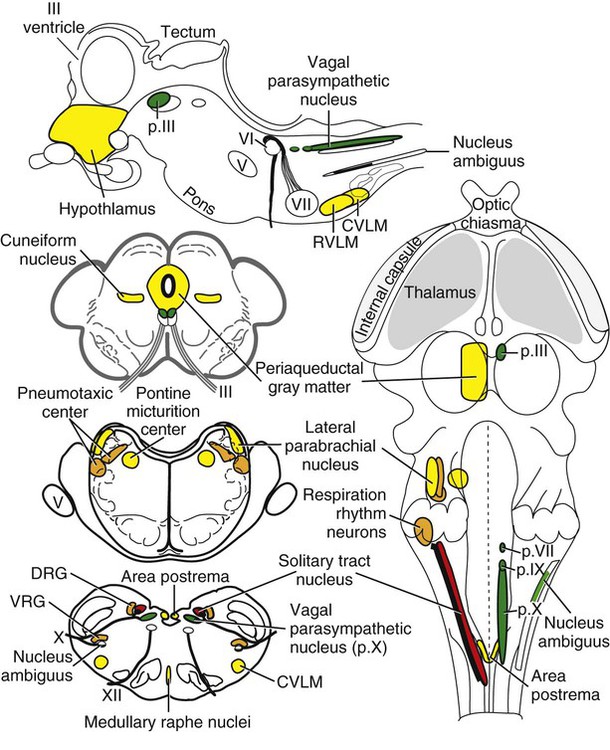

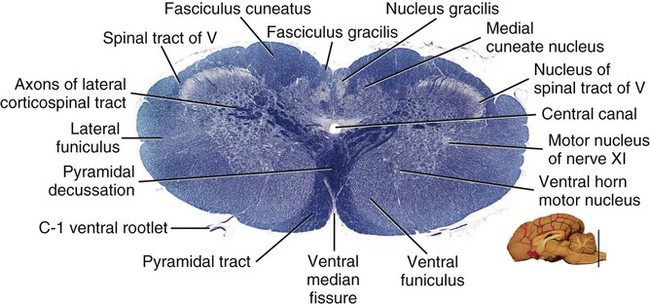

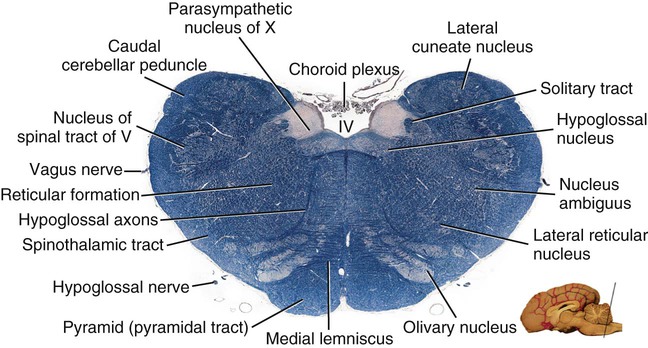

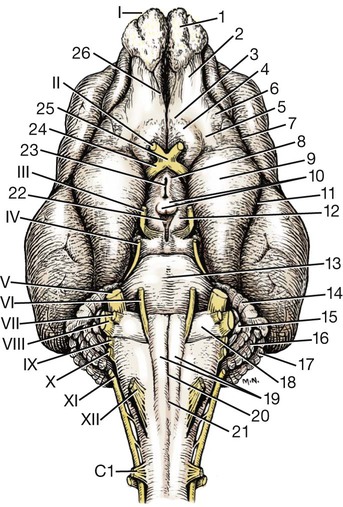

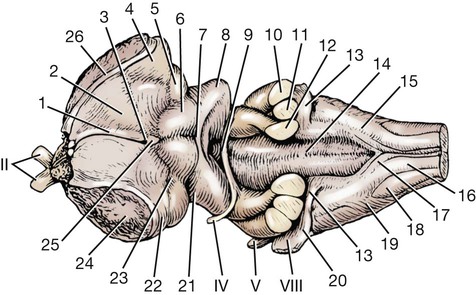

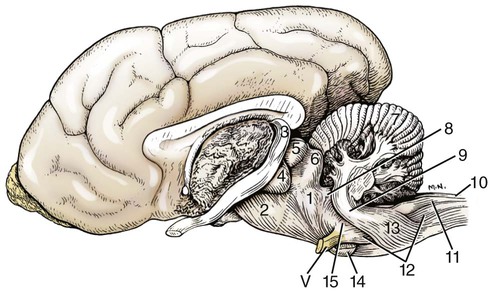

The brain develops from three enlargements of the rostral end of the embryonic neural tube (Table 18-1). The enlargements become the forebrain (prosencephalon), midbrain (mesencephalon), and hindbrain (rhombencephalon). Subsequently the forebrain and hindbrain differentiate further, producing five primary divisions of the brain: telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon, metencephalon, and myelencephalon (Fig. 18-1). TABLE 18-1 The brain may also be divided into three large regions: cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem (Fig. 18-2). The cerebrum is the telencephalon, the cerebellum is the dorsal part of the metencephalon, and the brain stem encompasses the remaining primary divisions. This chapter is organized to present first the brainstem, then the cerebrum, and finally the cerebellum. A ventral view of the brainstem reveals the primary brain divisions that compose it and the cranial nerves that emerge from it (Fig. 18-3). The medulla oblongata (myelencephalon) is the most caudal region. It is distinguished by bilateral longitudinal bands of white matter, the pyramids, that parallel the ventral midline. Seven cranial nerves (CN VI-XII) arise from the medulla oblongata. A transversely running trapezoid body demarcates the rostral extent of the medulla. Brain divisions are also evident in a dorsal view of the brainstem (Fig. 18-4). The dorsal surface of the medulla oblongata and pons features a rhomboid fossa (fossa rhomboidea), which is the floor of the fourth ventricle. Paired rostral and caudal colliculi mark the dorsal surface of the midbrain. Bilaterally, the diencephalon features a prominent thalamus and, more caudally, a metathalamus composed of medial and lateral geniculate bodies. 7. Commissure of caudal colliculi 9. Decussation of trochlear nerves in rostral medullary velum 10. Middle cerebellar peduncle 11. Caudal cerebellar peduncle 12. Rostral cerebellar peduncle 14. Median sulcus in fourth ventricle 15. Nucleus cuneatus lateralis 18. Spinal tract of trigeminal nerve 19. Superficial arcuate fibers 20. Cochlear nuclei (dorsal and ventral) 21. Brachium of caudal colliculus 23. Brachium of rostral colliculus 24. Cut surface of internal capsule In addition to distinct regions formed by gray matter nuclei and white matter tracts, the brainstem features extensive areas of reticular formation (formatio reticularis) where gray and white matter are mixed together. Neurons of the reticular formation give rise to reticulospinal tracts, to thalamic projections that alert the cerebral cortex, to cerebellar relay sites, and to visceral relay and premotor nuclei. Anatomically individual reticular formation nuclei are relatively indistinct but collectively they form three longitudinal zones: lateral and medial zones bilaterally and unpaired raphe nuclei located along the midline (Fig. 18-6). Many neurons within unpaired raphe reticular nuclei (nuclei raphe) release serotonin as a neuromodulator that affects mood and sensitivity to noxious stimuli. Raphe nuclei in the pons and midbrain send axons rostrally, influencing the limbic system and affective behavior. The nucleus raphe magnus of the medulla oblongata plays an endogenous analgesia role. Activated by axon input from midbrain periaqueductal gray (PAG) matter, the nucleus directs axons caudally to block nociceptive pathway transmission in the spinal cord dorsal horn via enkephalinergic interneurons (Beitz, 1992). The lateral nuclei of the reticular formation contain small (parvocellular) neurons. The nuclei are functionally diverse. They receive spinal input and activate reticulospinal neurons. They are involved in forebrain arousal (ascending reticular activating system). They project to the cerebellum. And many of the reticular nuclei scattered along the brainstem are involved processing visceral information (Fig. 18-7). Some visceral nuclei have a relay role, receiving visceral input and projecting their output to other visceral nuclei. Some visceral nuclei have a premotor role, their axons drive preganglionic neurons in visceral efferent nuclei. The caudal extent of the medulla oblongata has some features resembling the spinal cord, with which it is continuous (Fig. 18-8). In a transverse section, one can see a central canal, superficial white matter, laterally expanded central gray matter, a ventral median fissure, and a dorsal median sulcus and septum. A dominant feature of the spinomedullary junction is the pyramidal decussation (decussatio pyramidum). Each pyramid (pyramis) consists of myelinated axons that originate from neuronal cell bodies in the cerebral cortex. Axons within the pyramids go to the medulla oblongata (corticonuclear and corticoreticular axons) or to the spinal cord (corticospinal axons). The axons synapse on interneurons that regulate both efferent neurons (motor units) and projection neurons (cranial projecting pathways) (Davidoff, 1990). Dorsally at the midline, fasciculus gracilis axons terminate in the nucleus gracilis. Further laterally, fasciculus cuneatus axons terminate in the medial cuneate nucleus (nucleus cuneatus medialis) (Fig. 18-8). The fasciculi are composed of cranial branches of primary afferent axons associated with encapsulated receptors located in skin or in muscles, tendons, and joints. The nuclei relay sensory information from primary afferent neurons to neurons in the thalamus. Axons from the nuclei decussate as deep arcuate fibers (fibrae arcuatae profundae), and project rostrally as medial lemniscus (lemniscus medialis). The fasciculus and nucleus gracilis are concerned with discriminative touch from the caudal half of the body. Neurons situated medial and rostral to the nucleus gracilis are referred to as nucleus Z. Kinesthesia from the caudal half of the body reaches nucleus Z through a spinomedullary tract. Most kinesthetic input is from collateral branches of the dorsal spinocerebellar tract; only scant input arrives via the fasciculus gracilis (Hand, 1966). Lateral to fasciculus cuneatus, the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve (tractus spinalis n. trigemini) is visible (Fig. 18-8). It is superficial to the nucleus of the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve (nucleus tractus spinalis n. trigemini). The tract is composed of small, myelinated and nonmyelinated axons from neuronal cell bodies located in the trigeminal ganglion, plus a minority of somatic afferent axons from the vagus, glossopharyngeal, and facial nerves. The nucleus is divisible into rostral, interpolar, and caudal parts. The tract and nucleus extend into the first two cervical segments of the spinal cord overlapping with dorsolateral fasciculus, marginal nucleus, and substantia gelatinosa. The olivary nucleus (nucleus olivaris) is a prominent feature of the caudal medulla oblongata (Fig. 18-9). It is located dorsolateral to the pyramid and lateral to the medial lemniscus; it presents a distinctive serpentine profile in the ventrolateral medulla. The nucleus receives axonal input from the cerebellum, from the cerebral cortex via the pyramids, and from the red nucleus and PAG via the central tegmental tract. Dorsal and medial accessory olivary nuclei receive afferents from the spinal cord. The lateral cuneate nucleus (nucleus cuneatus lateralis) is situated most dorsally in the medulla oblongata. It receives proprioceptive input from the thoracic limb and neck via the fasciculus cuneatus. Axons from the nucleus form superficial arcuate fibers (fibrae arcuatae superficiales). The fibers merge with the dorsal spinocerebellar tract to form the caudal cerebellar peduncle, located at the dorsolateral margin of the medulla oblongata (Fig. 18-9). The dorsal spinocerebellar tract conveys proprioceptive information from the caudal half of the body. The floor of the fourth ventricle, designated rhomboid fossa (fossa rhomboidea), has a median sulcus (sulcus medianus) (Fig. 18-4). Bilaterally, a sulcus limitans marks the transition from floor to wall; also, it is the demarcation between the embryonic alar and basal plates. The roof of the fourth ventricle (tegmen ventriculi quarti) is formed by the tela choroidea (tela choroidea ventriculi quarti) a layer of ependyma and pia mater that attaches to the medullary wall along a line, called tenia of the fourth ventricle (tenia ventriculi quarti). Some cerebrospinal fluid enters the central canal, but most of it flows outward to the subarachnoid space, exiting the fourth ventricle bilaterally through a lateral recess (recessus lateralis) that leads to a lateral aperture (aperturae laterales). The recess and aperture are located immediately caudal to the caudal cerebellar peduncle. Some choroid plexus extends through the lateral recess and aperture to secrete directly into the subarachnoid space (Fig. 18-11). The motor nucleus of the hypoglossal nerve (nucleus motorius n. hypoglossi) is evident dorsally beside the midline (Fig. 18-9). Axons from the nucleus run ventrally and then angle through the lateral region of the olivary nucleus. They leave the medulla oblongata as roots of the hypoglossal nerve and innervate muscles of the tongue (somatic efferent axons). The parasympathetic nucleus of the vagus nerve (nucleus parasympathicus n. vagi) is located dorsolateral to the hypoglossal nucleus. Preganglionic parasympathetic visceral efferent axons from the nucleus run laterally to join the vagus nerve and innervate thoracic and abdominal viscera. Rostrally, two small nuclei of this cell column contribute axons to the glossopharyngeal and facial nerves (Fig. 18-9). The parasympathetic nucleus of the glossopharyngeal nerve (nucleus parasympatheticus n. glossopharyngei) innervates parotid and zygomatic salivary glands. Further rostrally, the parasympathetic nucleus of the facial nerve (nucleus parasympatheticus n. facialis) innervates mandibular and sublingual salivary glands and nasal, palatine and lacrimal glands. The nucleus intercalatus, positioned between the hypoglossal and the parasympathetic nuclei, sends axons to the cerebellum. The nucleus receives input from vestibular nuclei and there is clinical evidence that it is involved in holding vertical gaze position (Munro et al 1993). The solitary tract (tractus solitarius) is distinct dorsolateral to the parasympathetic nucleus of the vagus (Fig. 18-9). The tract contains axons from visceral afferent cell bodies located in distal ganglia of the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves and the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve. The axons synapse in the nucleus of the solitary tract (nucleus tractus solitarii). Caudally, right and left nuclei merge dorsal to the central canal, forming a commissural nucleus. The nucleus ambiguus is a column of sparse neurons located ventral to the nucleus of the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve (Fig. 18-9). Except for some visceral efferent neurons that innervate the heart (Fig. 18-7), the nucleus ambiguus contains somatic efferent neurons. Via vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves, the neurons send axons to striated muscles of the pharynx, larynx, and esophagus. A caudal continuation of the ambiguus cell column extends through the cervical spinal cord as the motor nucleus of the accessory nerve (nucleus motorius n. accessorii) (Fig. 18-5). Its axons form the spinal root of the accessory nerve, which innervates certain muscles of the neck (cleidocephalicus, mastoid part of sternocephalicus, omotransversarius, and trapezius). The accessory nerve has a cranial root that arises from the caudal pole of the nucleus ambiguus. The root immediately joins the vagus nerve and eventually becomes recurrent laryngeal nerve. The lateral reticular nucleus (nucleus reticularis lateralis), also referred to as nucleus of the lateral funiculus (nucleus funiculi lateralis), is located lateral to the olivary nucleus (Fig. 18-9). It receives input from the red nucleus and the spinal cord. Its axons join superficial arcuate fibers to reach the cerebellum via the caudal cerebellar peduncle. The motor nucleus of the facial nerve (nucleus motorius n. facialis) is located ventrally in the medulla oblongata (Fig. 18-11). The nucleus contains somatic efferent neurons that innervate muscles of facial expression. Neurons are topographically arranged within the nucleus: rostral to caudal positioned neurons innervate rostral to caudal muscles, dorsal neurons innervate ventral muscles, and vice versa (Berman, 1968). Axons from the facial nucleus stream dorsally and collect in a bundle that arcs, from medial to lateral, dorsally around the abducent nucleus, before proceeding ventrolaterally to exit passing through the trapezoid body (Fig. 18-5). The loop, located dorsal to the abducent nucleus, is referred to as the genu of the facial nerve (genu n. facialis). The facial nerve has a small contingent of general somatic afferent fibers that supply the concave surface of the auricle of the ear (Whalen & Kitchell, 1983). These axons join the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve. White matter at the lateral edge of the medulla oblongata constitutes the caudal cerebellar peduncle (pedunculus cerebellaris caudalis) (formerly restiform and juxtarestiform bodies). The axons of the peduncle pass deep to the acoustic stria and turn abruptly dorsad to join the cerebellum (Fig. 18-10). The lateral recess of the fourth ventricle is located immediately caudal to the abrupt turn of the peduncle (Fig. 18-11). 8. Rostral cerebellar peduncle 12. Spinal tract of trigeminal nerve 13. Superficial arcuate fibers 14. Trapezoid body (transected) 15. Location of pontine sensory nucleus of trigeminal nerve

The Brain

EMBRYONIC BRAIN DIVISION

DERIVED BRAIN STRUCTURES

DEFINITIVE BRAIN CAVITIES

Forebrain

Telencephalon

Cerebral hemispheres

Lateral ventricles

Diencephalon

Thalamus, hypothalamus, epithalamus, subthalamus, metathalamus

Third ventricle

Midbrain

Mesencephalon

Cerebral peduncles and tectum

Mesencephalic aqueduct

Hindbrain

Metencephalon

Pons and cerebellum

Fourth ventricle

Myelencephalon

Medulla oblongata

Fourth ventricle

The Brainstem

Reticular Formation Overview

The Medulla Oblongata

The Spinomedullary Junction

Caudal Half of the Medulla Oblongata

Level of the Facial Nucleus

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Brain

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue