2 The approach to the equine dermatological case

There are many important aspects involved in the clinical investigation of a dermatological case. Often, the main clinical evidence of skin disease and the reason for the owner seeking a veterinary consultation is visually obvious in some form or another but the skin is easily overlooked as an important mirror for the health of the horse. Also it is often the most abused organ as a result of neglect, repeated washing, over-energetic grooming, poor harness and blanket hygiene, and of course the horse’s own propensity for trauma. This means that often the primary clinical signs have been either obliterated or so altered and confused that it is hard to know whether any particular sign is the primary one.

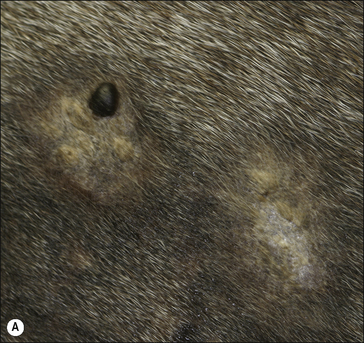

Intuitive supposition is often the mainstay of clinical practice – sometimes the signs are pathognomonic but even very experienced clinicians can make diagnostic errors when important aspects of the clinical process are not followed. A solid black spherical mass in the perineal skin of an aged grey mare may be assumed to be a ‘typical’ melanoma but it could be one of several different other options as well as one of several different types of melanoma (Fig. 2.1). Also a superficial glance at the skin may be grossly misleading. A close and detailed examination is an essential part of the diagnostic process even when the condition is apparently quite obvious. Often there are occasions when there are two distinct conditions present in the same field of view and then the clinician could easily overlook one of them (Figs 2.2 and 2.3).

Figure 2.3 This horse was presented for investigation of this pale wart-like area affecting the inner skin of both pinnae. A diagnosis of pinnal acanthosis (see p. 136) was made clinically. During the close examination a verrucose sarcoid was identified at the ear margin (arrow). Again the clinical approach is very different for the two conditions – the sarcoid has a much more threatening nature, and management options for the two conditions are very different.

Without a logical and systematic approach, there are few more frustrating situations than the diagnosis and treatment of skin disease in horses; treatment commonly fails when it is not focused on the cause of disease or recurrences develop when the pathogenesis and epidemiology are not considered. It is therefore essential that before any diagnosis is made, all the available facts are considered as a whole. Owners of horses commonly become distressed when skin problems fail to resolve, or even to follow a predicted course of treatment. Sometimes this leads to further frustration and often desperate measures such as seeking advice from non-professional sources or resorting to homeopathy. This may be a result of misinformation, misdiagnosis or in some circumstances improper treatment. There are some conditions that are extremely difficult to treat/manage and if the owner is not aware of these problems, there may be an unrealistic expectation.

Once the problem list has been established, a broad differential diagnosis can be formulated. Careful elimination of the various options may lead directly to a convincing diagnosis but it is a fact that the broad scope for diagnosis and the rather narrow panel of available signs means that further tests are often required in dermatological diagnosis (see Chapter 3). It is also important to recognize that the use of further tests will not necessarily lead to a diagnosis and so sensible judgements have to be made at all stages in the procedure and the owner apprised of the difficulties and the ‘likely diagnosis’. The maxim ‘communication is all’ is particularly applicable to equine dermatology. An accurate diagnosis can, however, often be made.

History taking (anamnesis)

The value of an individually formulated examination sheet (such as is shown in Fig. 2.7) cannot be overstated – it allows a structured, thorough questioning without omissions. However, even this may not always be totally comprehensive and the use of a structured form can sometimes be too prescriptive for unusual circumstances and presentations so they should be used with care. No information is too trivial – subtle facts may ultimately be the most significant. It is important to avoid undue repetitions but it may be necessary to ask questions in different ways to obtain the most helpful and reliable answers.

One of the most overlooked yet important aspects of skin disease is the management system employed by the owner (Fig. 2.4). Changes in management immediately prior to the onset of a significant urticaria might suggest some aspect of the change could be responsible. Failure to ask the right historical questions can be very limiting. It is often helpful in long-standing cases to ask the client to provide a chronological list of the disease’s progress, variation of feed or environment or of rider tack or harness which has been used. Management changes such as feed, water, bedding, pasture and transport, or unusual circumstances such as access to toxic waste or preservative-treated fence posts, should be established early.

Careful reviews of in-contact horses (or other species) and the environment are useful additions.

The local environment is also important and it can be helpful to examine the horse in its own circumstance (see Fig. 2.4). Local disease surveillance can help enormously in some circumstances. For example, epizootic lymphangitis is endemic in some parts of Ethiopia but absent in others. In spite of the breed predilection of the Icelandic horse for insect bite hypersensitivity, the condition is very rare in Iceland because there are few (if any) Culicoides spp. insects there. Local knowledge is often helpful.

The specific disorder history

How have these progressed (with or without treatment)?

Progression of disease is a critical issue but this is affected markedly by attempts at treatment. Particular attention should be paid to previous diagnostic tests, diagnoses and attempts at treatment (by owners, well-meaning lay people and/or previous veterinary surgeons). The nature of practice sometimes makes this difficult to establish, but it is important to determine whether any measures have had significant effects on the course of the condition (for better or worse) and questions may have to be rephrased to get a true answer. For example, asking ‘What medication has been applied already?’ may get a quite different answer from ‘Have you put anything on the horse?’ Of course I could ask ‘What is this medication that I can see/smell?’… even if I can’t!

Are other animals also involved?

Including the historical information on a ‘dermatological examination form’ provides a record of these events. It is often possible to come to a broad conclusion as to the nature of the case based upon the history alone (Fig. 2.5).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

.

.