Chapter 39The Antebrachium

Anatomy

The antebrachium lies between the elbow and carpus and is composed principally of the radius and small vestigial portion of the ulna and the flexor and extensor muscles. The tendons of the superficial and deep digital flexor muscles, the accessory ligament of the superficial digital flexor tendon, and the carpal sheath are discussed elsewhere (see Chapters 69, 70, and 75). The medial aspect of the antebrachium is relatively devoid of soft tissue coverage, and this is important when considering fractures of the radius. Major neurovascular structures include the median artery (continuation of the brachial artery in the proximal antebrachium), vein, and nerve; the radial, ulnar, and cutaneous antebrachial nerves; and the accessory cephalic and cephalic veins.

Clinical Diagnosis and Imaging Considerations

Lameness associated with the antebrachial region is relatively unusual. Clinical signs are obvious in horses with unstable radial fractures or in those with marked soft tissue swelling. In others diagnosis can be challenging, and ruling out other causes of forelimb lameness and then using diagnostic imaging to reach a definite diagnosis may be necessary. Perineural analgesia of the median and ulnar nerves (see Chapter 10) is performed to rule out more distal sources of pain.

Osteochondroma of the Distal Aspect of the Radius

See Chapter 75 for a discussion of osteochondroma of the distal aspect of the radius.

Physeal Dysplasia of the Distal Aspect of the Radius (Physitis)

See Chapter 57 for a discussion of physitis.

Radial Fractures

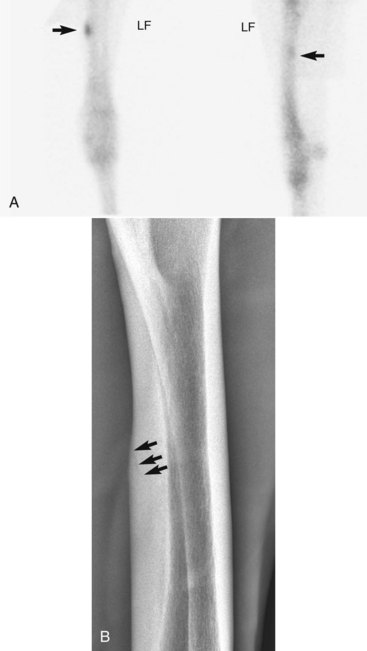

Radial fractures almost always result from external trauma, often a kick from another horse in adults, or from being stepped on or kicked by a mare in foals. Stress fractures of the radius also occur,5,6 but in our experience true stress fractures of the radius are rare, and the description of those reported by others is similar to what we have termed enostosis-like lesions (see the following discussion). One of us (MWR) recently evaluated images of a 4-year-old Thoroughbred colt in race training, with a history of sudden left forelimb lameness, with a genuine radial stress fracture involving the medial, middiaphyseal cortex (Figure 39-1). Cortical location of stress fractures as determined scintigraphically and radiologically differentiates this injury from enostosis-like lesions.

Clinical signs depend on the severity and location of the fracture. Horses with complete fractures (which are nearly always displaced) are severely lame (non–weight bearing, grade 5) and have marked soft tissue swelling associated with the fracture itself or the site of the original wound. The limb may have an unusual angle, and crepitus is usually audible and palpable. Often an associated wound results from the initial injury or is caused by fragment penetration, especially on the medial aspect of the antebrachium. Horses with incomplete or nondisplaced fractures have moderate to severe lameness (grade 3 to 5) shortly after the injury, but within 12 to 72 hours they are often fully weight bearing and walking with minimal lameness. However, resumption of exercise or turnout often results in the fracture becoming displaced within 1 to 2 days (see Figure 3-4). Horses with true stress fractures have moderate lameness (grade 1 to 3) at a trot.

For horses with complete, displaced (unstable) fractures of the radius the diagnosis is straightforward. Radiology is needed only to define fracture configuration and to determine if repair is possible. Radiographs are essential in the initial evaluation of any horse with a wound in the antebrachium or over the proximal aspect of the carpus that has a history of acute, moderate-to-severe lameness associated with the injury. Lameness associated with incomplete or hairline fractures of the radius may be transient, but radiographs often reveal obvious or suspicious fracture lines (Figure 39-2, A). Any radiological evidence of bone injury, often a localized cortical fragmentation or compression fracture, warrants high suspicion of an incomplete fracture, and a full series of radiographs should be obtained. Any horse that has persistent lameness after antebrachial trauma in which original radiological findings were negative should be reevaluated within 7 to 10 days, when a fracture may be evident. The horse should be confined to box rest in the interim. Diagnosis in horses with incomplete fractures or stress fractures can sometimes be difficult. Scintigraphic examination is important to differentiate fracture from other problems of the radius, such as enostosis-like lesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree