29 The acute abdomen

Differential diagnoses of acute abdomen are discussed in Chapter 8 and some of the most common disorders are discussed in greater detail here using case examples.

Septic (Bacterial) Peritonitis

Case example 1 – surgical gastrointestinal wound dehiscence

Clinical Tip

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood collected via the catheter for an emergency database. This was unremarkable except for the presence of a subjective neutrophilia with mild to moderate toxic change (see Ch. 3).

Case management

Morphine (0.3 mg/kg slow i.v.) was administered for analgesia. An abdominal ultrasound was performed using a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) protocol. This involved scanning the dog in lateral recumbency and obtaining both transverse and longitudinal views at each of four sites – just caudal to the xiphoid process (last sternebra), on the midline over the urinary bladder, and at the right and left flank regions. Despite this thorough evaluation, no peritoneal fluid could be identified. However, given the dog’s history and clinical signs, there was a very high index of suspicion for bacterial peritonitis secondary to surgical gastrointestinal wound dehiscence and a diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) was therefore performed (see p. 294).

Clinical Tip

Case example 2 – uterine rupture

Major body system examination

Assessment

Clinical Tip

Case management

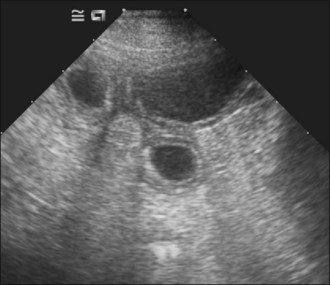

Aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation with an isotonic crystalloid solution was commenced and morphine (0.3 mg/kg slow i.v.) administered. Abdominal ultrasound revealed the presence of enlarged uterine horns distended with hypoechoic fluid consistent with pyometra and peritoneal fluid was detected (Figure 29.1).

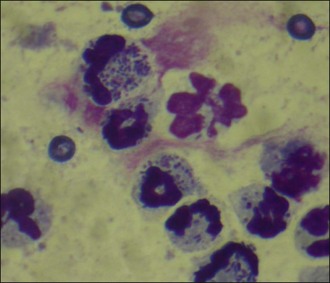

Abdominocentesis (see p. 293) was performed and a sample of the fluid retrieved. Cytology demonstrated large numbers of degenerate neutrophils with intracellular bacteria as well as a considerable number of extracellular bacteria (Figure 29.2). A diagnosis of bacterial peritonitis secondary to uterine rupture was made. Regrettably, due to financial constraints, the dog was euthanased.

Haemoabdomen

Causes of haemoabdomen are listed in Box 29.1.

Case example 3

Case management

Aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation with an isotonic crystalloid solution was commenced (60 ml/kg bolus via pressure infusor). Abdominal ultrasonography revealed the presence of a large volume of echogenic peritoneal fluid. Abdominocentesis (see p. 293) was performed and the non-clotting haemorrhagic fluid was found to have a PCV of 30%; cytology of the fluid revealed red blood cells, occasional erythrophagocytosis, no platelets and no evidence of sepsis. An abdominal counterpressure bandage was applied and fluid therapy discontinued as soon as the dog was assessed as being adequately perfused. The dog remained stable subsequently and the abdominal bandage was removed gradually over several hours.

Clinical Tip

Uroabdomen

Causes

Trauma is the most common cause of uroabdomen:

Neoplasia and prolonged urinary tract obstruction are less common causes.

Diagnosis

Clinical Tip

Bile Peritonitis

Diagnosis

Clinical Tip

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree