CHAPTER 30Testicular Abnormalities

A wide variety of testicular abnormalities have been reported in horses. Some adversely affect fertility, whereas others are benign lesions that have no significant impact on spermatogenesis. An accurate diagnosis of the pathologic condition will greatly aid in treatment recommendations and in forming a prognosis for future fertility.

ANORCHIA, MONORCHIA, AND POLYORCHIA

Anorchia is defined as an absence of testicular tissue and monorchia as a condition in which only one testis is present. These conditions can be congenital or acquired (as with surgical removal of a testicle). Congenital anorchia and monorchia are rare.1–3 When seen as congenital pathologic conditions, the epididymides are usually missing, as well as the testes. In most cases of congenital monorchia in horses, a vaginal process can be identified on the side without a testicle, leading to the suggestion that the condition arose during gestation secondary to severe degeneration of a previously existing testis. Only rarely was a vaginal process not present, thus suggesting that the problem was due to unilateral testicular agenesis.4 Polyorchia (the presence of one or more supernumerary testis) has been reported but is exceedingly rare.2,5,6

CRYPTORCHIDISM

A cryptorchid horse is one in which one or both testicles have not descended into the scrotum. This condition can be unilateral or bilateral and is relatively common in the stallion.7–9 The retained testicle may be present either in the inguinal canal or in the abdominal cavity. Abdominal testicles can be located anywhere from just caudal to the kidney to within the internal inguinal ring; however, most are located in or adjacent to the internal inguinal ring.10 Normal spermatogenesis does not occur in cryptorchid testicles, but hormone production is relatively unaffected. Thus, although stallions with one cryptorchid testicle and one normal descended testicle are usually fertile, bilaterally cryptorchid stallions are sterile but will continue to exhibit stallion-like behavior.

Cryptorchidism should be suspected in any stallion presenting with only one identifiable scrotal testicle or in a supposed gelding with excessively stallion-like behavior. A careful history must be obtained to determine if the missing testicle(s) was (were) surgically removed for reasons unrelated to cryptorchidism. In cases in which no scrotal testes are present, blood hormone profiles can be used to determine whether or not a nonscrotal testis is present. A single, baseline blood testosterone assay may be diagnostic because most cryptorchid animals have elevated testosterone when compared to geldings. However, there is some variation in baseline testosterone concentrations in both normal and cryptorchid animals. Thus this test can result in false-negative results on occasion. Alternatively, a human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) stimulation test can be performed. Documentation of a rise in blood testosterone in response to hCG stimulation is considered diagnostic of a retained testicle and is a more accurate test than a single baseline blood testosterone assay. Paired plasma samples are drawn before and 30 to 120 minutes after administration of 6000 to 12000 IU hCG intravenously. If functional testicular tissue is present, a significant rise in plasma testosterone concentrations will occur.11 This technique is reportedly over 90% accurate in detecting the presence of testicular tissue.12 However, it has been reported that the response to hCG stimulation depends somewhat on the location and number of retained testicles.13 Unilateral cryptorchids have been reported to have the greatest rise in peripheral plasma testosterone in response to hCG, regardless of the location of the cryptorchid testicle. Horses with bilateral inguinal testicles produced a lower response to hCG than did unilateral cryptorchids, and animals with bilateral abdominal testicles produced a still lower response.

Because of the potential variation in response to hCG, and because the standard hCG stimulation test results in a false-negative response in approximately 8% of cryptorchid animals, in cases in which clinical signs suggest that testicular tissue is present but standard hormone analyses do not confirm this suspicion, extended sampling (up to 72 hours post hCG administration) may be indicated to identify a rise in serum testosterone.14

Measurement of plasma total conjugated estrogens also has been used to diagnose the presence of a retained testicle and can be very reliable in differentiating cryptorchid stallions from geldings.12 Animals with testicular tissue have significantly higher plasma conjugated estrogens than do geldings. Alternatively, or in addition to blood hormone testing, ultrasonography can be used to identify the presence and location of a retained testicle. In one report, 11 of 11 retained testicles were accurately identified, located, and measured using a 5-MHz linear array transducer either transrectally (abdominal testicles) or by scanning externally over the external inguinal ring (inguinal testicles).15 Ultrasonography is particularly useful in animals with one scrotal testis because hormonal assays cannot differentiate between animals with two testicles (one in the scrotum and the other cryptorchid) and animals with only a single, scrotal testicle.

Debate exists over the heritability of cryptorchidism in the horse. The condition has been reported to be more prevalent in Quarter Horses, Percherons, and American Saddle Horses, thus suggesting a genetic component.12 Because of the suspicion that cryptorchidism is at least partially heritable, because many breed registries consider cryptorchid animals to be unsound, and because cryptorchid testicles may be at increased risk for neoplasia,16 bilateral castration of affected animals is strongly recommended.17 Until more information becomes available on the heritability of cryptorchidism, cryptorchid stallions, whether fertile or not, should be classified as unsatisfactory prospective breeders.18

In humans, several hormonal treatments have been reported to cause the descent of cryptorchid testicles with mixed results.19,20 To the author’s knowledge, these protocols have not been evaluated in horses in controlled studies and so are not recommended. Orchiopexy can be used to anchor an undescended testis into the scrotum. However, this technique does not result in the return of normal spermatogenesis.10 Any attempt to either medically or surgically correct a cryptorchid testicle for the purpose of selling, showing, or marketing the animal as a normal stallion is unethical.

TESTICULAR TORSION

Testicular torsion is more appropriately termed spermatic cord torsion. Torsion of the spermatic cord may cause resultant testicular problems if it results in vascular compromise to the testis. Torsions of less than 180 degrees often do not result in any overt clinical signs, and so treatment classically has not been recommended. Interestingly, recent Doppler ultrasonographic studies have shown that, in some animals with asymptomatic cord torsions, blood flow to the testicle is altered slightly. This raises some concerns that the problem may have more of an impact on testicular function than was previously believed.21 However, to date, there is no information to suggest that asymptomatic torsions adversely affect testicular function or fertility, and the standard of care for asymptomatic animals remains no treatment.

In some cases of torsions less than 180 degrees, and in many torsions of greater than 180 degrees, blood flow to the testicle can be severely impaired. In addition, lymphatic and venous stasis can result. In these cases, clinical signs are usually apparent. Affected stallions present with signs of colic associated with an enlarged, painful testicle; enlarged scrotum; increased scrotal fluid; and an enlarged spermatic cord (Figure 30-1). Diagnosis typically can be made based on observation and palpation of the affected area. Analgesics and tranquilizers usually are required to adequately examine the affected testicle and spermatic cord. Careful palpation will reveal a twisted and enlarged spermatic cord. In association with the torsion, the tail of the epididymis is rotated from its normal caudal position. The exact location of the epididymal tail depends on the degree of rotation of the cord. For example, 180-degree torsion would result in the tail of the epididymis pointing cranially. Ultrasonography can be used to confirm the diagnosis, if needed.22 Ultrasonographically, the lumina of the vessels of the spermatic cord are distended. In addition, the ultrasonographic character of the testicular parenchyma is altered. In acute cases of spermatic cord torsion, echogenicity of the testicular parenchyma may be decreased due to static blood and lymph. In more chronic cases, echogenicity may be increased as a result of clotted blood and fibrin. Associated hydrocele often is present. Torsion of the spermatic cord has also been reported in cryptorchid testicles.16

The usual treatment for spermatic cord torsion with vascular compromise is castration of the affected testicle. However, if the affected testicle is viable, it can sometimes be salvaged surgically by correcting the torsion and performing an orchiopexy to prevent recurrence.23 If the contralateral testicle was normal before the torsion, salvage of the affected testicle often is not necessary because sperm can still be obtained from the unaffected testis. If the torsion and associated inflammation and hydrocele cause an increase in scrotal temperature, a transient decline in semen quality from the contralateral testicle can be expected. Once thermoregulation is returned to normal, the contralateral testicle should return to normal function within one spermatogenic cycle and the stallion should again be fertile.

NEOPLASIA

Testicular neoplasia is uncommon in the stallion.24 Although one tends to associate neoplasia with an increase in size of the affected tissue, most testicular neoplasms in the stallion are relatively small and so are seen in association with either no change in testicular size or with a decrease in testicular size. Small testicular size in the presence of a testicular tumor most often is due to coincident testicular degeneration (TD). Because both testicular neoplasia and TD are seen most commonly in older stallions, it is not clear whether or not testicular neoplasia is a direct cause of TD. It seems likely that pressure necrosis of parenchyma surrounding a growing tumor will result in some localized degree of TD. However, in many cases, both testicles are uniformly degenerate, even though only one testicle is affected by a tumor. In these cases, is seems likely that the tumor and the degeneration are coincident, but not causative. Uncommonly, testicular tumors in the horse may result in an enlarged testicle.

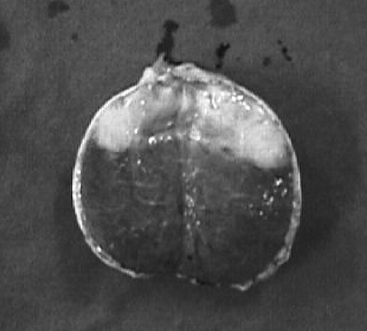

Testicular neoplasms in the horse can arise from either germinal or nongerminal cells, and most are benign. Germinal neoplasms are the most common tumor type found in stallions. Teratomas, seminomas, teratocarcinomas, and embryonic carcinomas are all germinal neoplasms that have been described in the horse (Figure 30-2).25 Nongerminal tumors arise from stromal cells and include Sertoli and Leydig cell tumors.26 A mixed germ cell-sex cord-stromal neoplasia has also been reported.27

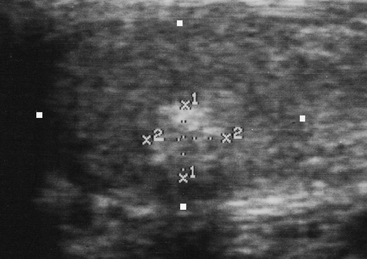

A tentative diagnosis of a testicular tumor can be made ultrasonographically. However, a definitive diagnosis requires histopathologic examination of the abnormal tissue. Ultrasonographically, testicular neoplasia results in a localized heterogeneous appearance to the normally very homogeneous testicular parenchyma. Most testicular tumors are well demarcated and are hyperechoic with respect to the surrounding testicular parenchyma (Figure 30-3).

Because most testicular tumors in the horse are benign, if a suspected tumor is small with respect to the surrounding testicular parenchyma, and if it does not appear to be aggressive, no treatment may be required other than periodic monitoring of the tumor’s progression. If coincident TD is not present, it is likely that the unaffected testicular parenchyma will continue to function and contribute sperm to the ejaculate. If a tumor is aggressive and is growing rapidly in size, orchiectomy can be considered. However, even locally invasive testicular tumors usually do not metastasize. So again, it may be possible to do nothing other than monitor the neoplasia. In theory, histologic evaluation of an ultrasonographically guided testicular biopsy sample can aid in the decision as to whether or not to remove the testicle. In practice, the additional information gained from a biopsy sample may not be worth the risk of damage to the testicle that may be incurred during procurement of the sample. In humans, testis-sparing surgery for removal of benign testicular tumors has been described.28 Cryosurgery has been used in one horse in this author’s clinic with a benign testicular tumor. The cryosurgery was intended to halt the growth of the tumor and prevent further pressure necrosis and degeneration of the surrounding testicular parenchyma. Unfortunately, regrowth of the tumor continued in spite of the procedure.

Keep in mind that malignant testicular tumors have been reported in equids.29–32 In particular, seminomas in the stallion may have a greater tendency to metastasize than do seminomas in other species.2 Should the decision be made to leave an affected testicle in place, this unlikely possibility should be discussed with the animal’s owners.

ORCHITIS

Orchitis, or inflammation of the testis, is a rare cause of testicular enlargement in the stallion. Orchitis can arise secondarily to trauma, ascending or descending infection, parasites, or autoimmune disease.33 The affected testicle is typically enlarged, hot, and painful. Systemic signs such as fever, leukocytosis, and hyperfibrinogenemia may also be present. If semen is collected and evaluated, large numbers of white blood cells are typically found and semen quality is often poor. Cultures of ejaculated semen may aid in identification of the causative organism in cases of infectious orchitis. In stallions the ultrasonographic appearance of an affected testicle appears to be similar to what has been described in humans.34 The affected testis may be hypoechoic with respect to the unaffected testis. The decrease in echogenicity may involve the entire testicular parenchyma uniformly, or it may be seen isolated to focal areas within the parenchyma. Hydrocele, epididymitis, and thickening of the scrotal skin also may be present.35

Bilateral orchitis is associated with a guarded prognosis for future fertility33 because, in severe cases, the resultant inflammation and increases in local temperature can result in fibrosis and degeneration of the testicular parenchyma. However, if one testicle is unaffected by the problem, the chances for return to normal fertility are greatly improved. If orchitis is suspected and the desire is to salvage the affected testis (testes), treatment should be initiated as soon as possible. Systemic antibiotics, ideally based on culture and sensitivity of the causative organism, should be included. In addition, antiinflammatory drugs and cold hydrotherapy should be included in the treatment plan. Alternatively, if the opposite testicle is normal, unilateral orchiectomy can be performed. After resolution of the inflammatory process, the unaffected testicle should return to its prior level of function and fertility may be restored.