Chapter 22 Terminology, behavioral pathology, and the Pageat (French) approach to canine behavior disorders

Introduction

Another fundamental discussion regarding the idea of classification and diagnosis is related to the interpretation of behavior problems as normal adaptive responses, or alternatively as dysfunctional conditions. Defining the boundaries between normal and abnormal behavior is a very difficult and controversial topic not only in veterinary behavioral medicine but also in human psychiatry. Language is a very important matter so that using terms like clinical signs, symptoms, syndromes, or diagnoses could indirectly lead to the assumption that we are in fact dealing with pure pathological conditions. For all these reasons, many authors support a more open and flexible way of categorizing behavior problems which takes into account the natural variability of behavior and the fact that a behavior problem may or may not be related to an underlying dysfunctional state.1

A good example of the aforementioned elements of discussion is a group of problem behaviors in dogs that can be broadly termed as aggression toward family members. A review of the literature on this subject demonstrates that each author may use particular classifications and terminology.2 In some cases, differences are just related to the words used to describe more or less the same conditions, whereas in others, deeper discrepancies are found regarding the biological interpretation of this behavior problem. Indeed, owner-directed aggression has been linked to different underlying causes, from a hierarchical conflict between the dog and its owners to simply an active avoidance reaction in contexts of conflict. Further, for some authors these forms of aggression are mostly considered an expression of normal behavior, whereas for others, they are often linked to a pathological state.

Some years ago a comprehensive system for the classification of behavior disorders in dogs was developed by French colleagues based on the analysis of more than 11 000 clinical cases. This approach partially follows the philosophy of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)3 system for the diagnosis of mental disorders in human beings, which itself is in draft for a fifth version (DSM-5) at the time of writing. Basically a list of well-defined and discrete categories of behavioral disorders is offered based on the observation of specific clusters of signs and symptoms. Each diagnostic category is considered the result of an underlying dysfunctional state (see glossary, Table 22.1). This assumption is reflected in the terminology used (i.e., sociopathy, hypersensitivity–hyperactivity (HS–HA) syndrome, Cocker spaniel dysthymia) as well as in the fact that psychotropic drugs are included in the treatment for the vast majority of disorders. Similarly to the DSM system, disorders are clustered in sections according to the patient’s age. One patient can show more than one of these conditions together. In addition to classifying behavior problems, the Pageat or French approach presents an alternative pharmacopoeia in terms of recommended drugs, as well as doses and indications.

Table 22.1 Glossary of terms used in the Pageat (French) approach

| Bulimia | Conditions of increased food intake due to an emotional disorder. Pageat links bulimia to states of either permanent anxiety or chronic depression |

| Deficitary sign | Any clinical sign that represents a decrease in social interactions, communication and motivation |

| Depressive state | A reactive state characterized by a diminished receptivity to stimuli and a spontaneously irreversible inhibition |

| Dysthymia | A state characterized by sudden fluctuations of mood, impulsiveness, stereotypies, a lack of social inhibition, sleep disorders, and feeding disorders |

| Encopresis | Defecation in the resting location during a period of rest |

| Enuresis | Urination in the resting location during a period of rest |

| Normothymics | Mood stabilizers |

| Potomania | Psychogenic polydipsia |

| Productive sign | Any clinical sign that appears or increases its normal frequency or intensity |

| Antiproductive sign | Any clinical sign that decreases its normal frequency or intensity |

The Pageat (French) approach to behavior counseling

The main purpose of this chapter is to review part of this alternative approach, including some of the scales developed to assess the patient’s behavior. All the information in this chapter has been adapted from Pageat.4 Dr. Pageat’s approach to senior pet behavior problems can be found separately in Chapter 13. Note that the diagnoses and treatments reported here are based on Dr. Pageat’s research and writing.

Scales

Currently, three scales are utilized that have been partially validated in terms of reliability and sensitivity. The scale for assessment of old dogs, known as the Age-Related Cognitive and Affective Disorders (ARCAD) scale, is discussed in Chapter 13.

Scale for evaluation of aggressiveness

The global aggressiveness index and social aggressiveness index are calculated from the scores obtained in Form 22.1 using the following eight parameters:

1. owner’s attitude toward the dog

3. frequency of aggressive manifestations

7. reaction after owner’s reprimand

Form 22.1

Evaluation grid of aggressiveness in dogs (client form #7, printable version available online)

| Score | ||

|---|---|---|

| A: Attitude of the owner towards the dog | ||

| Frightened | 4 | |

| Apathetic, carefree | 3 | |

| Disappointed | 2 | |

| Anger | 2 | |

| B: Use of the dog | ||

| Guard and defense | 3 | |

| Herding | 2 | |

| Companionship | 2 | |

| Breeding, show | 2 | |

| C: Frequency of aggressive manifestations | ||

| Daily | 5 | |

| Weekly | 4 | |

| Monthly | 3 | |

| Very spread out | 2 | |

| Never* | 1 | |

| D: Gender | ||

| Castrated male | 3 | |

| Spayed female | 3 | |

| Male | 2 | |

| Female | 2 | |

| E: Age of the dog | ||

| >5 years | 5 | |

| 1–5 years | 3 | |

| <1 year | 1 | |

| F: Description of the bite | ||

| It releases but remains threatening | 5 | |

| It releases and goes away quietly | 4 | |

| The dog holds assertively (not shaking and tearing) | 3 | |

| It releases and hides | 1 | |

| G: Reaction after reprimand from the owner | ||

| The dog defends itself | 4 | |

| It tries to flee | 2 | |

| It accepts punishment | 1 | |

| H: Degree of access of dog | ||

| The whole house | 4 | |

| All rooms excepts the parents’ bedroom | 3 | |

| The whole house except the bedrooms | 2 | |

| Limited to a few rooms | 2 |

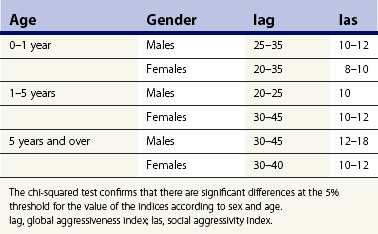

It is also possible to compare the values obtained for a given patient with the norms of its age and sex group (Table 22.2). These measurements help to simplify differential diagnoses of behavioral changes associated with an aggressive case:

• In primary hyperaggressiveness (idiopathic or caused by lesions), aggression is type 3. Iag is strongly increased (35–40%) while Ias remains unchanged or decreases slightly (10–15%). The ratio between the indices is strongly decreased. This type of aggression is abnormal in sequence, intensity, context, and/or degree of inhibition.

• In reactional aggressiveness (while this type may be normal, it is essentially stage 1 of sociopathies), only the Ias index is increased. It may then represent 70–90% of Iag. Aggressions are of type 1 or 2 form.

• In secondary hyperaggression (instrumentalization of the previous types), both indices are increased and aggression is type 3. The ratio between the indices is often quite close to normal values.

This scale was published by Pageat in his text4 using 270 control dogs and 132 dogs suffering from behavioral disorders (Table 22.2).

Scale for evaluation of emotional and cognitive disorders (EDED scale)

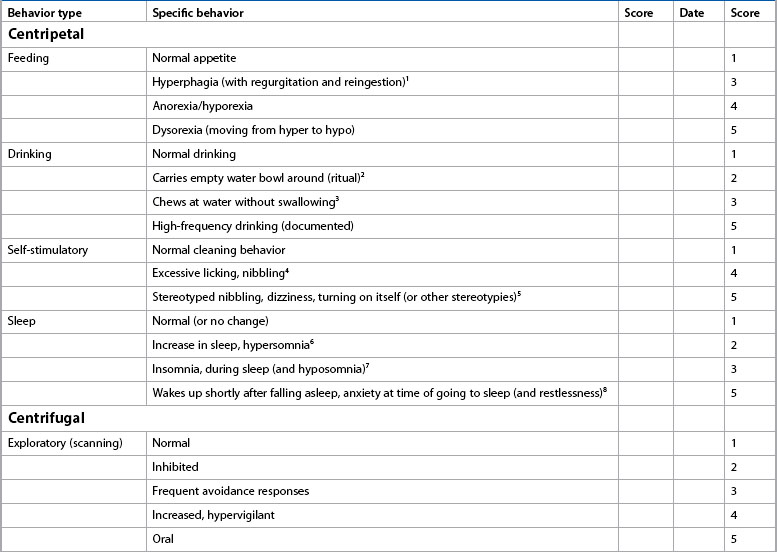

1. centripetal behavior: self-centered behaviors are termed centripetal. They include abnormalities of feeding, drinking, elimination, and sleep and somatoesthesic behavior

2. centrifugal behavior: behaviors resulting in a modification of the environment (i.e., exploration, aggression)

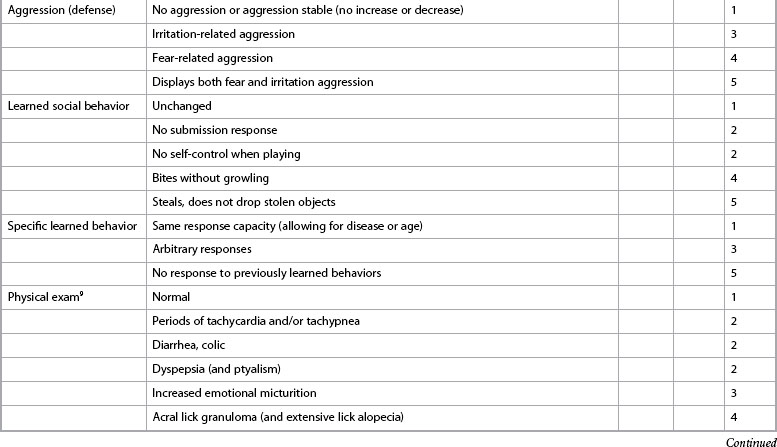

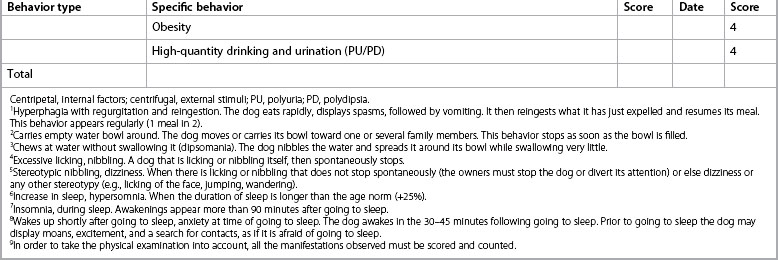

The presence of a behavior in the grid does not mean that it has to be pathological, but only that it is statistically associated with clinical pictures of emotional disorders. With each category, some selected types of behavior are taken into account and the different configurations that they may take are assigned an arbitrary numerical score between 1 and 5. The highest score is given to the poorest prognosis. The final mark, called the EDED value, is the result of adding all the scores together (Form 22.2 and Table 22.3).

Table 22.3 Interpretation grid of EDED scores

| EDED value | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 9–12 | Normal state |

| 13–16 | Phobias |

| 17–35 | Anxieties |

| 36–44 | Emotional (thymic) disorders |

Once clinicians have obtained this score, they can evaluate it using the interpretation grid (Table 22.3). As with the aggressiveness indices, the EDED score does not replace the clinical approach; it complements it, facilitates the differential diagnosis, and helps objectively evaluate the animal’s progress during treatment. As with the other forms, the evaluator and not the owner should complete the form.

The ARCAD scale

The calculation grid of the ARCAD score was constructed according to the same rules as EDED (see Chapter 13). While the parameters that make up both scales are very similar, they can have different diagnostic meanings. Therefore, while the EDED scale helps evaluate dogs of all ages, the ARCAD measurement provides a better means of assessing problems that might be specific to the older dog. For example, old dogs can obtain an EDED score of the anxious type, while their ARCAD score suggests a temperament disorder. The EDED scale is not designed to assess mood disorders (see Chapter 13), which have a more discrete symptomatology in old dogs. Moreover, the ARCAD scale helps discriminate affective disorders (emotional score) from cognitive disorders to determine if drugs such as selegiline might be indicated.

Disorders appearing during puppyhood or adolescence

Sensory homeostatic disorders

Hypersensitivity–hyperactivity syndrome

Description

These dogs have motor activity that appears to be overdeveloped. They cannot keep still. They run, jump, and never stop playing. The activities have almost complete absence of structure. No sequential organization can be found and, in particular, the appeasement phase that follows the achievement of the consummatory act is rarely found. Even with apparently normal activities (ball play, predatory play), the comparison with “normal” subjects of the same age helps establish that the consummatory phase is extended, which most often leads to a new appetitive phase. Everything happens as if there was no “stop signal” at the end of the sequence. During play fighting, the lack of an “inhibited bite” is observed in puppies aged 2 months and over. In addition, the total duration of the wakeful periods appears considerably greater in the most developed cases. These dogs sleep on average  out of 24 hours, which corresponds to a deficit of 30–50% of what is considered normal. Overall, the key element of this clinical condition is an extremely low reactive sensory threshold. Patients respond to very weak visual, tactile, or auditory stimulation. Each stimulus triggers a characteristic motor response (hypertrophied and ill structured). Marked oral exploration is often observed. Some of these cases may meet the criteria for hyperkinesis or hyperactivity, discussed in Chapter 14.

out of 24 hours, which corresponds to a deficit of 30–50% of what is considered normal. Overall, the key element of this clinical condition is an extremely low reactive sensory threshold. Patients respond to very weak visual, tactile, or auditory stimulation. Each stimulus triggers a characteristic motor response (hypertrophied and ill structured). Marked oral exploration is often observed. Some of these cases may meet the criteria for hyperkinesis or hyperactivity, discussed in Chapter 14.

Diagnosis

Two stages can be defined based on the presence or absence of sleep disorders.

Stage 1

• Absence of bite inhibition with pups aged over 2 months (bite inhibition is expected to be normally acquired before 2 months of age)

• Inability to stop a behavior sequence after the consummatory phase, and reappearance of an appetitive phase

• Almost normal dietary satiety

• Hypervigilance reflected by behavior responses to stimuli continuously present in the animal’s environment.

Prognosis

This depends on the stage of development and the duration of the clinical picture. It is especially the age at which treatment is started that seems to determine the establishment of self-control. An analysis of therapeutic results from 120 dogs, as published in Pageat’s text,4 relates to the juvenile period, but no particular age within this period. Conversely, subjects treated after the start of sexual activity respond less well to treatment, and good control of dietary behavior (dog continues to steal food) and activity level are rarely obtained. Stage 2 shows a greater resistance to treatment. Usually, dietary and sleep disorders require drug therapy for almost a whole year. Whatever the age when treatment is started, it seems necessary to warn owners of the handicap this illness constitutes for the learning of complex tasks (hunting, search and rescue, drugs and explosives detection, guide dog, hearing dog for the deaf, or dog for the disabled). An early diagnosis must therefore be encouraged to help owners have realistic expectations about the dog’s potential abilities and limitations. In all cases, it is essential to warn the owners of the long duration of the treatment (5–9 months).

Treatment

This is based on the administration of psychotropic drugs aimed at controlling the overactivity and the establishment of a higher sensory homeostatic threshold. In addition, play therapy may help to stabilize all the animal’s reactions. During drug therapy, different groups of psychotropic drugs may be used according to the clinical picture. Currently, selegiline is the reference treatment for this condition. Its dosage is 0.5 mg/kg taken in a single morning dose. In some stage 2 cases, establishing normal satiety and sleep duration requires the use of fluoxetine 1–2 mg/kg in one morning dose.5 Unfortunately, the improvement may disappear very quickly after the drug is discontinued. Therapy combines elements of play therapy and learning social inhibitions in techniques derived from direct social regression. We insist that play sessions are carried out with a lot of care and rigor. The main pitfall is that if the dog jumps when it has reached maximal excitement during play, it may mouth or bite its owner. In order to avoid these reactions, owners are advised to stop play as soon as the dog produces acts which are not strictly connected with the play offered (e.g., during ball play, very quick short running phases around the play area while the ball trajectory is straight). Moreover, when the dog starts to jump around its owners, they should avoid all interaction, including waving their arms, which unfortunately is the spontaneous reaction of many people when a dog jumps on them.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree