Chapter 14. Surgical Interventions in Cancer

Eric R. Pope

Surgery is an integral part of comprehensive cancer treatment. Surgery can be used to establish a diagnosis, achieve a cure, palliate clinical signs, aid patient support, or reduce tumor burden in order to maximize the efficacy of other treatment modalities Thorough preoperative assessment is important to avoid over-treating or, more commonly, under-treating a patient. Two of the most important questions that should be considered prior to any surgery are: (1) What is the most appropriate surgical procedure, if any, for this patient? and (2) Do I have the skills and expertise to perform this surgery? A poorly planned or executed surgery can have profound negative effects on a patient with a potentially curable tumor. It is better to perform staged procedures (e.g., biopsy followed by definitive surgery) if knowing the type or grade of tumor could influence the aggressiveness of the definitive surgery. Performing a less-aggressive surgery because of lack of familiarity with a procedure or concerns about ability to close a wound is generally not in the patient’s best interest. See Box 14-1 on p.144 for common mistakes related to surgical oncology.

BOX 14-1

COMMON MISTAKES RELATED TO SURGICAL ONCOLOGY

1. “Wait and see”—Few masses resolve spontaneously. Waiting only provides time for further growth and metastasis. There are few contraindications to FNA or needle core biopsy to obtain a diagnosis.

2. “It shelled out nicely” —Except for lipomas and a few other benign masses, close marginal excision invariably leaves tumor in the wound bed. Additional surgeries typically must be more aggressive because of altered tissue planes.

3. “It looks benign” —Although some tumors have a characteristic appearance, it is not possible to accurately diagnose or rule out cancer based on gross appearance of a mass alone. If surgical excision is warranted, so too is histopathological examination of the excised tissue.

4. “I only submitted the masses that looked suspicious” —If multiple masses are removed, all should be submitted for histopathology. This is especially true for canine mammary masses, since benign and malignant lesions are often present concurrently.

5. “It’s an old dog (cat)” —Age is not a disease. Treatment options should be offered and the decision left to the owner.

BIOPSY (see Chapter 6 for detailed descriptions)

In most instances, the diagnosis should be established before the definitive surgery. 1-4 If that is not possible because of the location of the tumor or inability to obtain a diagnostic sample, intraoperative evaluation can be performed. Fine-needle aspirates (FNAs), impression smears, and/or frozen sections can provide valuable information for intraoperative decision-making. The results of these tests may be helpful in avoiding over- or under-treating patients and in helping pet owners decide whether or not to continue treatment. The ability to use these techniques obviously depends upon the availability of a cytopathologist to process the samples in a timely manner.

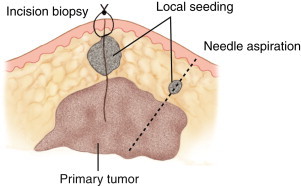

Surgical biopsies can be either incisional or excisional. Incisional biopsy is indicated when the diagnosis cannot be established by less invasive methods, and knowing the diagnosis might influence the aggressiveness of the surgical procedure. 5,6 Incisional biopsy is most commonly used for lesions on or near the skin surface. Deeper lesions can usually be adequately sampled by needle core biopsy, especially when image guidance is used. 7,8 Incisional biopsies should include normal tissue at the edge of the lesion as long as new tissue planes will not be invaded. 3,5,9 Removing a deep, narrow wedge of tissue facilitates closure of the biopsy site. Inflamed, ulcerated, and necrotic areas should be avoided because they often interfere with obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Incisional biopsies—all biopsies, for that matter—should be performed so that the biopsy tract can be excised during the definitive surgery without altering the surgical plan 1,3,5 ( Figure 14-1 ). Failure to remove the entire biopsy tract increases the risk of recurrence because of potential seeding of the tract with tumor.

|

| FIGURE 14-1 Incisional biopsy. The biopsy should be planned so that new tissue planes are not opened. The biopsy site can be sutured closed while awaiting results, and the biopsy tracts will be removed when the definitive surgery is performed. |

Excisional biopsy is indicated when the type of surgery would not be influenced by establishing a definitive diagnosis preoperatively, 3,5 such as a primary lung tumor or a dermal mass located in an area where additional surgery, if needed because of dirty margins, would not result in significantly increased morbidity. Excisional biopsy should not be performed as a convenience to the owner or to avoid multiple procedures (diagnostic and then therapeutic) because an incomplete excision can have a negative impact on treatment options and the ability to achieve a cure if the mass is malignant. Excisional biopsy should be performed adhering to the guidelines shown in the section “Surgery for Local Control” later in this chapter.

CYTOREDUCTION (DEBULKING)

The concept of cytoreductive surgery is often misunderstood and misused. The goal is to reduce the tumor burden to enhance the efficacy and/or reduce the morbidity associated with other treatments. It should not be considered a primary treatment modality. Simply removing easily accessible parts of a large mass is unlikely to improve the final outcome and may result in significant patient morbidity, particularly if wound healing complications occur. One gram of tumor in a wound leaves approximately 1 billion tumor cells. 10 In many instances, the tumor left in the wound is from the most biologically active areas of tumor (capsule or pseudocapsule), and tumor regrowth is often rapid.

Ideally the tumor burden should be reduced to microscopic levels when performed prior to radiotherapy or chemotherapy. 11 Marginal excision of a mass meets this criterion (see subsequent discussion). Since radiation therapy and chemotherapy interfere with wound healing, these procedures are often delayed after surgery to allow the surgical wound to heal before initiating therapy. Unfortunately, the longer the delay, the greater the chance that significant regrowth will occur, particularly if gross tumor is left within the wound or it is an aggressive tumor. Radiation therapy should be delayed for at least 1 week after surgery, but a recent study showed that there was not a significant improvement in wound healing if radiation therapy was delayed longer (Henry CJ, personal communication, 2003).

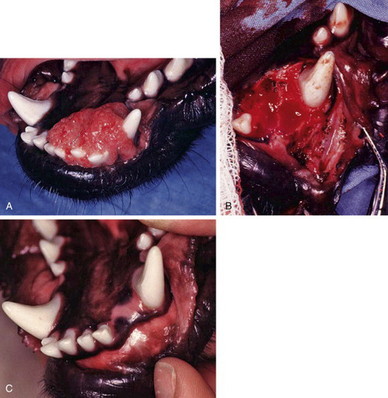

Cytoreductive surgery may also be performed in conjunction with photodynamic therapy (see Chapter 17 ). The goal in this instance is to reduce the depth (thickness) of the tumor to less than the depth of penetration of the light source used to activate the photosensitizer. A potential benefit of this approach is an improved ability to maintain cosmetic appearance and function, compared with traditional surgical methods. An example is the use of photodynamic therapy to treat oral squamous cell carcinoma. 12 Superficial tumors with limited bone involvement may be effectively treated without having to perform a segmental mandibulectomy ( Figure 14-2 ).

|

| FIGURE 14-2 A , Oral squamous cell carcinoma. B , Tumor has been surgically debulked to a thickness <1 cm prior to photodynamic therapy. C , Healed site. Excellent cosmetic appearance and function have been maintained. (Courtesy of Dr. Dudley McCaw, Kansas State University.) |

SURGERY FOR LOCAL CONTROL

Complete surgical excision of many benign and malignant tumors can be curative or provide long-term remission. The adage that the first chance is the best chance should guide preoperative planning. 1,2 Surgery for recurrent tumors is typically more complicated because differentiating scar tissue from tumor can be difficult and potential seeding of tissue planes opened during the prior surgery necessitates a more extensive resection. 1,2

Preoperative Management

Complete staging to determine the local and distant extent of disease is essential for preoperative planning. 2 Routine use of the TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) system to document the extent of disease is recommended. 13,14 Recording the location(s) and size(s) of all masses and presence or absence of regional lymph node or distant metastasis is also important for assessing response to treatment during follow-up evaluations. The regional lymph nodes should be assessed preoperatively by palpation and/or imaging techniques. FNA or needle biopsy should be performed preoperatively. If the results are questionable, the lymph node(s) can be removed for biopsy during the definitive surgery. Advanced imaging techniques such as CT and MRI (see Chapter 10, Section B ) are also useful for planning, particularly for cases where there is concern about the ability to completely excise a mass because of invasion into important structures. This is especially true with soft-tissue sarcomas, for which tumor margins may be difficult to discern at the time of surgery.

Preoperative blood work should be consistent with the suspected tumor type, physical examination findings, and American Society of Anesthesia classification. The minimum data base for most cancer patients includes CBC, biochemical profile, and urinalysis. Consult the chapters on specific tumor types for more detailed recommendations concerning preoperative assessment.

Infection rates after oncologic surgery have been shown to be significantly higher than for other surgical procedures. 4 The decision to administer perioperative antimicrobials should be based on anticipated length of the anesthesia/surgical period, whether or not the use of implants is anticipated or are pre-existing (e.g., pacemaker or total hip replacement implants) and if infection would have a catastrophic effect on the outcome of the procedure. Prophylactic perioperative antimicrobials are generally not continued for longer than 24 hours after surgery unless there is a demonstrated therapeutic need.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree