Chapter 11 Surgical drains perform three main functions: • Removal of pre-existing fluid or air from a wound/body cavity • Preventing anticipated fluid or air accumulation within a wound/body cavity. Whilst the first two therapeutic functions are widely accepted, the latter prophylactic use of surgical drains can be a controversial area. The use of surgical drains to remove pre-existing fluid or air is most commonly from a fluid-filled peripheral swelling, e.g., salivary mucocele or abscess, or from a body cavity. The removal of fluid from a surgical site is desirable due to the negative effects of the fluid on the host’s resistance to infection.1 This occurs via several mechanisms (Box 11-1). Drains are placed routinely during thoracic surgical procedures to evacuate postoperative pneumothorax and to remove either pre-existing or anticipated fluid, which may cause respiratory compromise. In the abdomen, drains are used predominantly for the purposes of removing septic exudate, e.g., in cases of septic peritonitis. Removal of transudates, modified transudates or blood is rarely of benefit to the patient. The most common indication for the prophylactic placement of a surgical drain is in combination with reconstructive surgery and the use of cutaneous and myocutaneous flaps. There is evidence within the veterinary literature that seroma formation is a common sequel to these procedures and that drain placement reduces the prevalence of this and subsequently of wound dehiscence and flap failure.2–4 Whether or not prophylactic drain placement is beneficial following other surgical procedures, however, remains controversial. In human medicine, Cochrane Systematic Reviews investigating the prophylactic use of surgical drains in orthopedic surgery, thyroid surgery, and incisional hernia repairs have failed to show any benefits in drain placement, but have shown some clear disadvantages, e.g., prolongation of hospital stay.5–7 In veterinary medicine, there is a distinct lack of published data on this subject, eliminating the use of an evidence based approach; thus surgeons are reliant upon anecdotal evidence and their own experience to determine whether a drain should be placed in any individual case. Experimental studies have documented prolonged tissue healing and reduced blood supply to cutaneous wounds in the cat compared with the dog, which may predispose to seroma formation in cats; however, clinical studies to support this have not been performed.8–11 In addition, cat owners may be poorly compliant at restricting exercise, allowing behavior such as jumping, which may contribute to problems with wound healing and seroma formation. Omentum can be used as an autogenous wound drain (Fig. 11-1). Its beneficial properties include promotion of angiogenesis, improved immune function, and tissue fluid drainage and it has been used successfully to promote healing of a variety of wound types in cats, particularly axillary collar wounds (see Chapter 18) and indolent pocket wounds, which are both challenging to treat by other methods.12,13 The use of omentum is, however, limited by its availability and the location of the wound: complications such as necrosis of the omental fat and incisional herniation through the omental exit point from the abdominal cavity have been reported.12 For information on how to create an omental flap see Chapter 19. The use of a bandage to maintain apposition of tissue planes is a suitable alternative to a surgical drain in some locations, e.g., distal limb.14 However, there are many anatomical locations where application of a bandage is difficult or where it may compromise normal function, e.g., cervical and thoracic regions. In addition, cats are often poorly tolerant of dressings and their presence may reduce feeding and normal behavior postoperatively. Penrose drains are composed of soft latex and are a flattened tube of variable diameter (0.25–1 inch) (Fig. 11-2). They are readily available, easy to use and cheap, making them a popular choice. This type of drain relies on gravitational forces, capillary action and overflow for wound drainage and therefore is limited to use in locations where these forces can be utilized. Penrose drains placed on the head or dorsum, or exiting from the lateral or dorsal aspects of a surgical site are unlikely to function and will instead contribute to complications of wound healing. The gravitational and capillary action of fluid drainage is related to the surface area of the drain and thus fenestration of these drains is contraindicated. In addition to reducing the efficiency of the drain, fenestration will also predispose to breakage of the drain during removal. Penrose drains are indicated for use in superficial wounds where there is pre-existing or anticipated fluid production and should have a single ventral exit point. Allowing the drain to have a second exit point proximally is not recommended.15 This serves only to increase the risk of wound infection and air transmission through the wound, without conferring any advantages to the patient. The main use of the double exit technique has traditionally been to prevent subcutaneous emphysema developing in areas of high motion, e.g., the axilla or inguinal region, where air may be sucked into the wound by a single exit point; however, this is not usually considered to be a significant clinical problem.16 After placement, where location permits, the drain should be covered by a sterile absorbent contact layer and bandage. This is for collection of the fluid produced, and to reduce the risk of introduction of hospital or environmentally acquired pathogens. The dressing should be changed according to the rate of fluid production from the wound. In locations where bandaging is not possible or would likely result in additional complications, petroleum jelly or similar is applied liberally to the clipped area ventral to the drain to prevent fluid from scalding the skin and to allow easy cleaning of the area. The problems of feline intolerance to dressings and requirements for sedation for dressing changes, thus increasing morbidity and cost, should be taken into consideration when using these drains. The technique of drain placement and removal is described in Box 11-2.

Surgical drains

Indications

Alternatives to surgical drains

Omentum

Pressure bandage

Types of drains

Passive drains

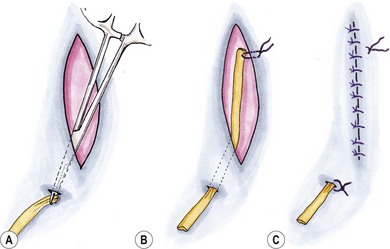

Penrose drains