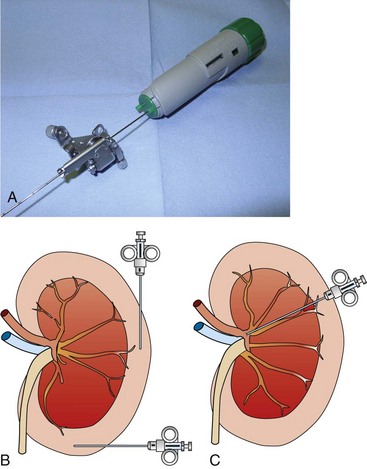

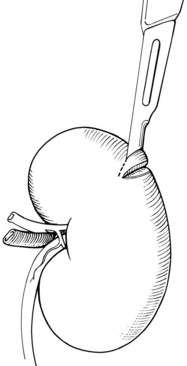

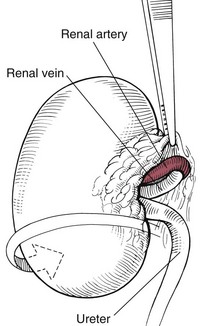

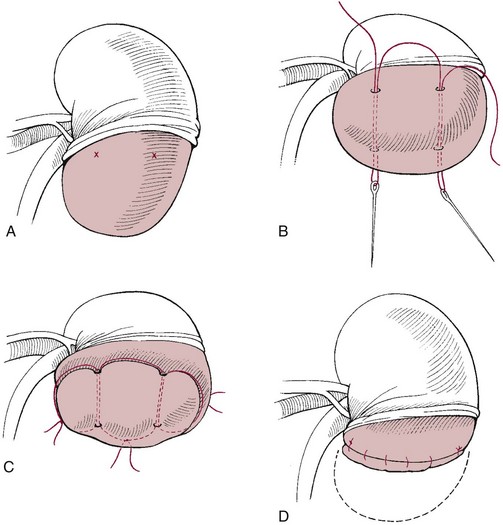

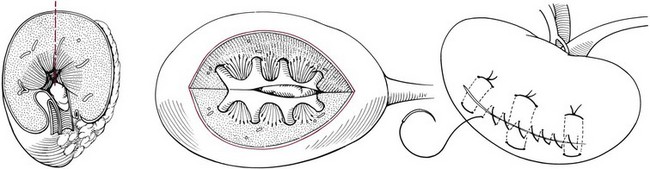

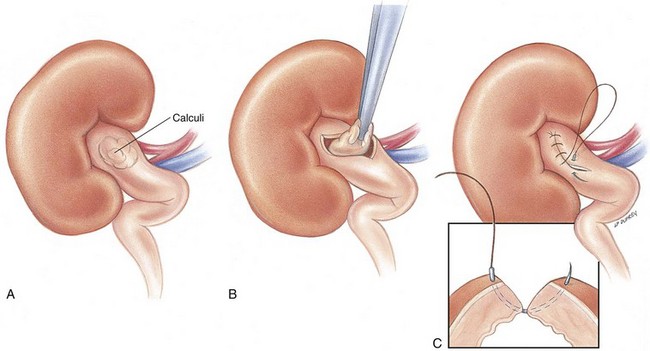

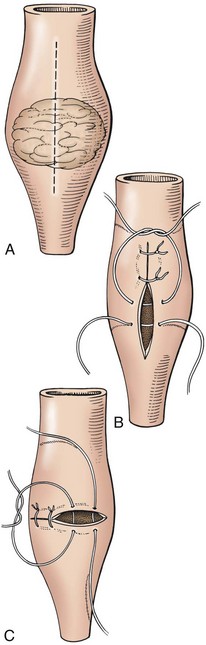

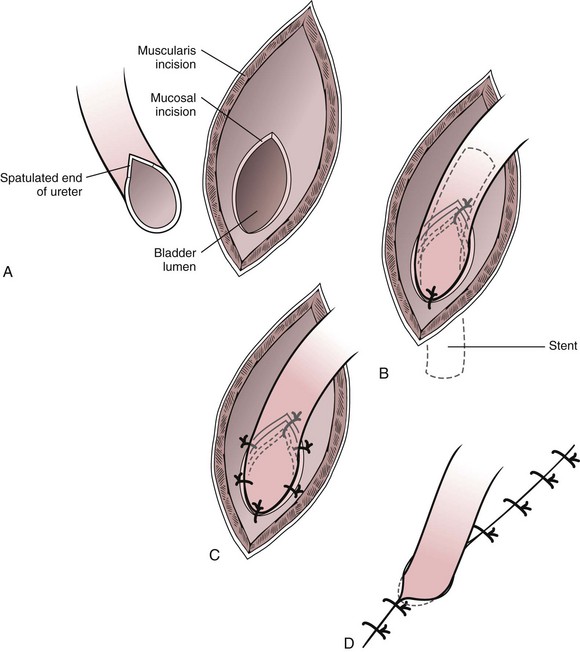

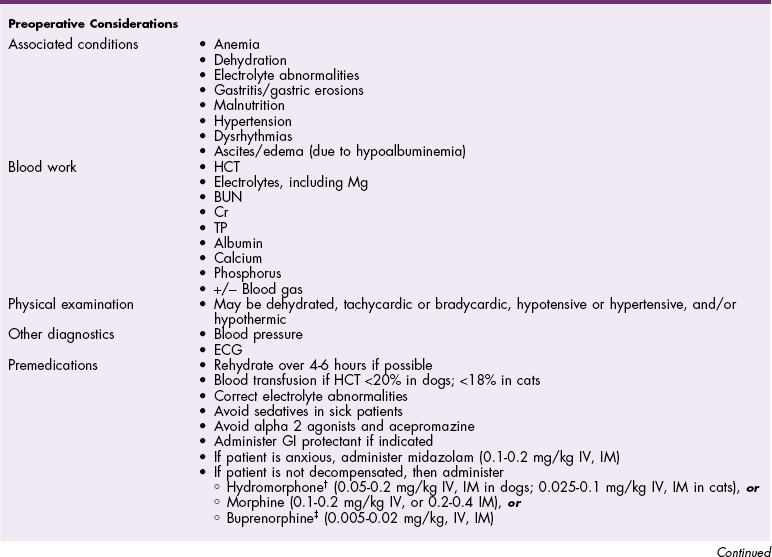

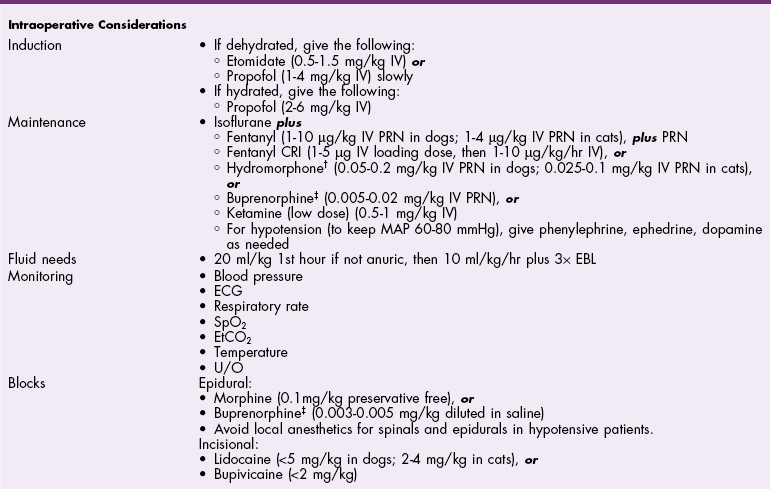

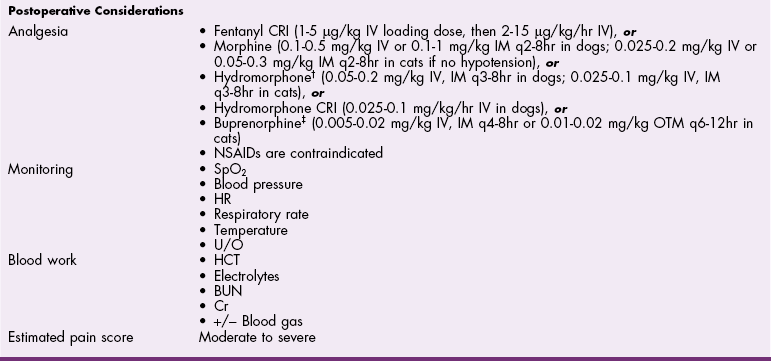

Chapter 25 General Principles and Techniques Nephrectomy is excision of the kidney; nephrotomy is a surgical incision into the kidney. Nephrostomy is the creation of a permanent fistula leading into the pelvis of the kidney; temporary nephrostomy tubes (nephropyelostomy) are occasionally used to divert urine when obstructive uropathy occurs or when the proximal ureter has been avulsed from the kidney. Pyelolithotomy is an incision into the renal pelvis and proximal ureter; a ureterotomy is an incision into the ureter; both are generally used to remove calculi. Neoureterostomy is a surgical procedure performed to correct intramural ectopic ureters; ureteroneocystostomy involves implantation of a resected ureter into the bladder. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) refers to patients with markers of structural or functional kidney damage of longer than 3 months’ duration. A staging system for CKD has been proposed by the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) for canine and feline CKD (Box 25-1), reflecting degrees of creatinine concentration with substages regarding proteinuria and blood pressure. Renal failure is defined as when 75% of nephrons in both kidneys cease to function. Chronic renal failure (CRF) refers to patients with CKD with significant clinical signs (polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss, decreased appetite) and laboratory findings (azotemia, anemia, proteinuria). Damage to the kidney is usually irreversible because nephrons are replaced by fibrous connective tissue. Acute renal failure (ARF) may also be referred to as acute kidney injury (AKI) and refers to patients that have an abrupt decline in renal function usually caused by an ischemic, toxic, or infectious insult. Sometimes this becomes confusing; animals with CRF or CKD can become acutely worse if reasons for acute injury are superimposed upon the chronic condition (i.e., acute on chronic kidney failure). Animals with later stages of CKD are typically anemic owing to diminished renal erythropoietin production. Elevated circulating parathormone concentrations may also have a negative effect on erythropoietin concentrations. Gastric ulceration, bleeding, or increased red cell fragility may occur in uremic patients. Coagulation profiles are warranted in animals with severe kidney disease. Normally hydrated animals with a packed cell volume (PCV) below 20% or a hemoglobin level less than 5 g/dl may benefit from preoperative blood transfusions (see Box 4-1 on p. 30). Severely anemic patients should be transfused if the hematocrit is low (<18% in cats; <20% in dogs) before induction of anesthesia; these animals will benefit from oxygen before, during, and after anesthesia (see p. 31). Anticholinergic drugs should be given as needed to prevent or treat bradycardia. Medications that should be avoided in patients with renal compromise include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aminoglycosides, and some contrast agents. Compound A, a by-product of sevoflurane, causes renal failure in rats; however, research does not support this finding in dogs, cats, and humans. In the human literature, it is recommended to use sevoflurane at an oxygen flow rate greater than 2 L/min to protect against nephrotoxicity in compromised patients, or to use isoflurane. Ketamine at low doses or as a low-dose constant rate infusion (CRI) generally is not contraindicated in animals with renal disease. However, in chronically ill or compromised patients, ketamine can cause problems when used at induction doses. Ketamine stimulates the sympathetic nervous system and inhibits reuptake of norepinephrine. The effect of ketamine relies on adequate catecholamine stores to support blood pressure during induction. In chronically ill or severely compromised patients, catecholamine stores may be depleted, resulting in marked hypotension and bradycardia when this drug is used. The following general anesthetic principles should be considered in animals with renal disease (Table 25-1). The patient may be premedicated with an anticholinergic if bradycardic (i.e., atropine or glycopyrrolate) and an opiate. If the animal has minimal renal compromise, a thiobarbiturate or propofol can be used for induction. Ketamine should be avoided in chronically ill dogs and cats with renal compromise. If a dog is severely depressed, hydromorphone plus diazepam (see Table 25-1) may allow intubation. If additional drugs are needed (see Table 25-1), a reduced dose of etomidate, thiobarbiturate, or propofol may be administered IV. Anesthetic Considerations for Animals with Renal Disease* @Buprenorphine is a better analgesic than morphine in cats. *Patients with renal disease may have decreased volume of distribution and decreased clearance of many drugs. It is recommended to start with low doses and titrate slowly to effect. †Monitor for hyperthermia in cats. Animals with renal calculi, ectopic ureters, or urinary tract obstruction may have concurrent infections and should be given appropriate antibiotics based on urine culture and susceptibility testing; alternatively, antibiotics can be withheld until appropriate intraoperative cultures have been taken. Potentially nephrotoxic antibiotics (i.e., aminoglycosides, tetracycline [except doxycycline], and sulfonamides) should be avoided. Penicillins and cephalosporins (e.g., ampicillin, amoxicillin, cefazolin, cephalexin; Box 25-2) are highly concentrated in urine. They are effective against most Gram-positive organisms; cephalosporins also have an enhanced Gram-negative spectrum. Fluoroquinolones (e.g., enrofloxacin; see Box 25-2) have broad activity against aerobic Gram-negative bacteria. Drug doses or dosing frequency should be altered as required by the degree of renal compromise. Renal biopsy may be indicated to determine a definitive diagnosis in dogs and cats with renal disease, or to provide an estimate of the severity or reversibility of renal damage. It may be performed at surgery, or it may be done percutaneously by ultrasonography, laparoscopy, or digitally using a keyhole abdominal incision. Ultrasound-guided and laparoscopic biopsies are the preferable percutaneous techniques. Renal biopsy should be avoided in patients with bleeding disorders, large intrarenal cysts, perirenal abscesses, severe hydronephrosis, and obstructive uropathy. Administering fluids before, during, and shortly after biopsy to initiate and maintain a mild diuresis may reduce formation of blood clots in the renal pelvis, which could cause hydronephrosis. Spring-loaded biopsy needles, biopsy guns, or manual devices (e.g., Tru-Cut) may be used to obtain a sample, but manual devices are not recommended because they can easily produce fragmented tissue samples. Advantages of the spring-loaded devices are that they can be manipulated with one hand and often obtain better samples with less artifact, especially when guided by ultrasound. Sixteen gauge needles are often used, but 18 gauge needles are typically adequate and may be easier to use in smaller patients. Attention to detail is critical; a good quality sample obtained with an 18 gauge needle is more useful than a ragged or fragmented sample from a 16 gauge needle. In healthy dogs, serial ultrasound-guided renal biopsies were not found to induce functional changes in the kidneys or histologic changes that might be confused with progressive renal disease (Groman et al, 2004). Needle biopsies are often inadequate when juvenile-onset renal disease (i.e., renal dysplasia) is evaluated because of nonuniform distribution of lesions; wedge biopsies are preferred in such cases. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsies require heavy sedation or preferably general anesthesia. Place the patient in ventrodorsal recumbency. If generalized diffuse disease is suspected, as occurs with glomerular disease, the right kidney is the preferred side for a biopsy because it is technically easier to perform. However, either kidney may be sampled from this position. Clip the hair over the biopsy site and aseptically prepare it. Place a sterile sleeve over the ultrasound probe. Using sterile ultrasound coupling gel, identify and examine the kidney. Once the site of entry for the biopsy has been determined, make a small stab incision in the skin using a No. 15 Bard-Parker scalpel blade. The safest approach is to pass the biopsy instrument through the most lateral aspect of the kidney cortex; this is the area farthest from the major vasculature. Insert the biopsy device (e.g., an 18 or 16 g, single spring–fired biopsy core needle [E-Z Core Single Action Biopsy Device, Products Group International, Lyons, Colo.] or an automatic spring-loaded biopsy gun [e.g., Bard Biopty or Monopty single-use spring-loaded disposable biopsy instrument, C. R. Bard, Murray Hill, N.J.]) through the nick in the skin, and advance it until it just penetrates the kidney capsule (Fig. 25-1, A). Position the biopsy needle in such a way that a biopsy is taken of glomerular tissue in the renal cortex, rather than of medullary tissue (Fig. 25-1, B). Place the tip of the needle through the renal capsule before activating it to prevent sliding of the needle along the capsule and to avoid tearing the capsule. Fire the biopsy device, and retract the needle through the skin. Gently manipulate the sample from the biopsy needle, and place it onto a glass slide with physiologic saline. Cut the sample into three sections, and place one in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution for light microscopy and one in glutaraldehyde for electron microscopy; freeze one for immunofluorescence. Surgical biopsies may be performed using an automatic biopsy instrument (see previous discussion), a manual device (Tru-Cut or Franklin modified Vim-Silverman biopsy needle), or a wedge resection with a scalpel blade (Fig. 25-2). Spring-loaded devices are recommended because they are easier to use than manual devices, can be manipulated with one hand, and often produce superior tissue samples. Wedge resection allows a larger sample to be obtained than can be obtained with the use of needles or guns. With either technique, it is important to ensure that adequate amounts of cortical tissue are obtained. Perform a needle biopsy with a Tru-Cut-type instrument by placing the tip of the instrument on the kidney capsule with the obturator specimen rod fully retracted within the outer cannula. Position the biopsy needle as described previously (see Fig. 25-1). Push the specimen rod into the lesion by advancing the plastic handle or by triggering the firing mechanism. With manual devices, advance the outer sheath of the needle into the tissue to sever the biopsy sample. Withdraw the needle with the outer sheath over the specimen rod. Apply digital pressure to the site to control hemorrhage. Be sure the sample is long enough (see previous discussion) and primarily consists of cortical tissue. Process the sample as described previously. For a wedge biopsy, make an incision into the renal parenchyma with a No. 11 or a No. 15 scalpel blade. Make another incision at an angle to the first incision to remove a wedged-shaped piece of parenchyma (see Fig. 25-2) and apply digital pressure. Be sure to include cortex in the sample. Close the incision with a mattress suture of 3-0 or 4-0 absorbable suture material across the capsule. Grasp the peritoneum over the kidney and incise it. Using a combination of blunt and sharp dissection, free the kidney from its sublumbar attachments. Elevate the kidney and retract it medially to locate the renal artery and vein on the dorsal surface of the renal hilus (Fig. 25-3). Identify all branches of the renal artery. Double ligate the renal artery with absorbable suture (e.g., polydioxanone, polyglyconate, glycomer 631, poliglecaprone 25) or nonabsorbable suture (e.g., cardiovascular silk) close to the abdominal aorta to ensure that all branches have been ligated. Identify the renal vein and ligate it similarly. The left ovarian and testicular veins drain into the renal vein and should not be ligated in intact dogs. Avoid ligating the renal artery and vein together to prevent the formation of an arteriovenous fistula. Ligate the ureter near the bladder. Remove the kidney and ureter and, after procuring appropriate culture specimens, submit them for histologic examination. If possible, strip the renal capsule from the area of the kidney to be excised. Use absorbable suture (No. 0 or 1) with two long, straight needles attached. Thread the needles into the kidney at the proposed resection site (Fig. 25-4, A and B). Tie the thread into three separate ligatures, but avoid damaging the renal vessels or ureter (Fig. 25-4, C). Excise the renal tissue distal to these ligatures. Ligate any bleeders and suture the exposed diverticula with absorbable suture (2-0 or 3-0). Approximate the capsule over the end of the kidney (Fig. 25-4, D), and anchor it to the sublumbar tissues to prevent rotation of the kidney. As an alternative, clamp the renal vessels with vascular forceps and excise the kidney parenchyma. Ligate the parenchymal vessels and close the renal pelvis and diverticula. Suture the capsule as described previously and remove the clamps from the renal vessels. Nephrotomy usually is performed to remove calculi (see p. 726) lodged in the renal pelvis, but it may also be performed to explore the renal pelvis for neoplasia or hematuria. Nephrotomy should be avoided in patients with severe hydronephrosis because ample parenchyma may not be available to prevent postoperative urine leakage. In addition, nephrotomy may temporarily diminish renal function by 25% to 50%. Although bilateral nephrotomies can be performed, this could precipitate AKI if renal function is sufficiently compromised preoperatively. Staged procedures are indicated in such patients. Nephrotomy may be done by bisecting the kidney or by using an intersegmental approach whereby the plane of dissection follows the terminal branches of the posterior and anterior renal arteries. The interlobar arteries are not transected; this theoretically minimizes nephron destruction. Neither technique affected GFR in normal dogs, but because the bisection approach requires less surgical manipulation and time, it is the preferred technique (Stone et al, 2002). Locate the renal vessels and temporarily occlude them with vascular forceps, a tourniquet, or an assistant’s fingers. Mobilize the kidney to expose the convex lateral surface. Make a sharp incision along the midline of the convex border of the kidney capsule, then bluntly dissect through the renal parenchyma, ligating renal vessels as necessary (Fig. 25-5). Culture the renal pelvis. Remove the calculi and flush the kidney with warm saline or lactated Ringer’s solution. Assess the ureter for patency by placing a 3.5 French soft rubber catheter down the ureter and flushing it with warm fluids. Close the nephrotomy by apposing the cut tissues and applying digital pressure for approximately 5 minutes while restoring blood flow through the renal vessels (sutureless technique). As an alternative, appose the capsule with a continuous pattern of absorbable suture material (see Fig. 25-5). If adequate hemostasis is not achieved, or if urine leakage is a concern, place absorbable sutures through the cortex in a horizontal mattress fashion (see previous comments and Fig. 25-5). Then, suture the capsule in a continuous pattern with absorbable suture. Replace the kidney in its original location. Sutures may be placed in the peritoneum where the kidney was elevated to help stabilize it. Pyelolithotomy may be performed to remove renal calculi if the proximal ureter and the renal pelvis are sufficiently dilated. This procedure prevents trauma to the renal parenchyma associated with nephrotomy. Pyelolithotomy is extremely difficult if the ureter is not dilated. Dissect the kidney from its sublumbar attachments and expose the dorsal surface. Identify the ureter and renal vessels (Fig. 25-6, A). Make an incision over the dilated pelvis and proximal ureter, and remove the calculi (Fig. 25-6, B). Flush the renal pelvis and diverticula with warm saline to remove small debris. Next, flush the ureter to ensure its patency. Close the incision in a continuous pattern with 5-0 or 6-0 absorbable suture (Fig. 25-6, C). Make a transverse or longitudinal incision in the dilated ureter proximal to the calculi and remove them (Fig. 25-7, A). Place a small, soft rubber catheter into the ureter proximal and distal to the incision, and flush the ureter with warm fluid. Make sure that all calculi have been removed and that the ureter is patent. Close the incision in a simple interrupted pattern with 5-0 to 7-0 absorbable suture (Fig. 25-7, B). As an alternative, if the ureter is not dilated and if stricture formation seems likely, make a longitudinal incision over the calculi and close the incision in a transverse fashion (Fig. 25-7, C). If the ureter has been damaged, perform a resection and anastomosis (see next section) or a proximal urinary diversion via a nephropyelostomy tube (see p. 718). The diameter of the feline ureter is approximately 0.4 mm at the level of the bladder, and standard ureteroneocystostomy techniques often cause ureteral obstruction. Microsurgical techniques may be necessary to prevent ureteral obstruction in cats, particularly when the ureter is not dilated owing to disease (e.g., renal transplantation). A “drop-in” technique was originally described for ureteroneocystostomy of cats undergoing renal transplantation; however granuloma formation and hemorrhage were common. Extravesical techniques have largely replaced intravesical techniques in people. A recent study in cats suggested that the extravesical technique using a simple interrupted suture pattern was preferred over an extravesical technique using a continuous suture pattern or an intravesical mucosal apposition technique (Mehl et al, 2005). Although all three techniques resulted in renal pelvis dilation, the dilation resolved more rapidly with the extravesical technique using a simple interrupted pattern, and this technique was associated with consistently lower serum creatinine concentrations during the first postoperative week. To perform an extravesical simple interrupted suture pattern technique, make a partial-thickness incision through the muscularis and submucosa of the ventral aspect of the apex of the urinary bladder to expose the mucosa (Fig. 25-8, A). Spatulate the distal end of the ureter, and make an incision equal in length to the spatulation incision in the ureter through the bladder mucosa in the caudal aspect of the muscularis incision. Place a simple interrupted suture (6-0 or 8-0 nylon) between the proximal ureter at the end of the spatulation and the cranial aspect of the bladder mucosal incision, and a second interrupted suture between the distal end of the ureter and the caudal aspect of the bladder mucosal incision (Fig. 25-8, B). Place a 4-0 polypropylene stent into the lumen of the ureter to ensure patency. Place the stent after the first two sutures are tied, and remove it before tying the final sutures of the mucosal layer. Place two additional interrupted sutures between the ureteral and bladder mucosae on one side of the incision (Fig. 25-8, C). Close the seromuscular incision (Fig. 25-8, D).

Surgery of the Kidney and Ureter

Definitions

Preoperative Management

Anesthetic Considerations

![]() TABLE 25-1

TABLE 25-1

Antibiotics

Surgical Technique

Renal Biopsy

Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Biopsy

Surgical Biopsy

Needle Biopsy

Wedge Biopsy

Nephrectomy

Partial Nephrectomy

Nephrotomy

Pyelolithotomy

Ureterotomy

Ureteral Reimplantation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Surgery of the Kidney and Ureter