Chapter 8 Surgery of the Bovine Integumentary System

Wound Healing

DEBRIDEMENT

Ultimately, the fibrin clot formed during the inflammatory phase organizes, dries, and becomes a scab. The scab protects the underlying tissue from recurrent injury and maintains a moist environment for phagocytic cells and fibroblasts. It maintains a hypoxic and acidic environment that inhibits bacterial growth and stimulates fibroblast proliferation. In addition, the scab provides scaffolding for the second stage of wound healing, debridement. The platelets and fibrin that comprise the scab form a network of proteins and chemotactic factors that attract neutrophils and macrophages into the wounded area. The neutrophils and macrophages remove necrotic debris, foreign matter, and bacteria.

Wound Management

WOUND CLOSURE

Primary Wound Closure

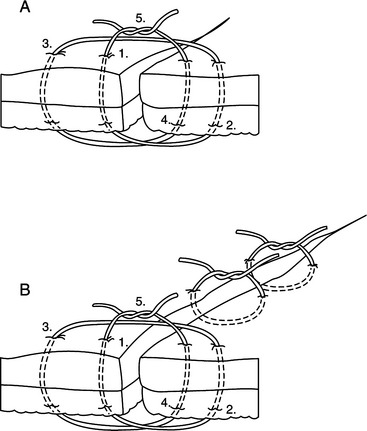

With primary wound closure, drainage is reduced, and contamination trapped in the wound site could cause abscessation. Also, excessive tension across the wound can cause pressure necrosis, suture failure, or can interrupt circulation and inhibit wound healing. If necessary, tension-relieving sutures can be placed initially and can be followed by simple interrupted sutures placed between the tension-relieving bites (Figure 8.1-1). Interrupted near-far-far-near tension-relieving sutures placed at regular intervals along the incision starting in the center work well to bring skin edges into apposition. For wounds under a lot of tension, using penetrating towel clamps to help align tissues may be necessary. Rubber stents or “quills” placed on the tension sutures help prevent tissue necrosis under the suture material. After 3 to 4 days, the tension sutures are removed, and the simple interrupted sutures are left for 10 to 14 days.

WOUND LAVAGE

Chlorhexidine Diacetate

Chlorhexidine solution at a 0.05% dilution (25 cc of 2% stock solution in 1 liter saline) has antibacterial effects without inhibiting wound healing, Chlorhexidine diacetate has a longer residual effect than povidone iodine and has shown greater efficacy in the presence of organic debris.