Chapter 69Superficial Digital Flexor Tendonitis

The first two sections of this chapter consider the general clinical manifestations of tendonitis and then the specific surgical management of tendonitis in racehorses. The third section discusses some of the variable clinical presentations in other competition and pleasure horses and factors influencing treatment and prognosis. In this chapter we have chosen to retain the term tendonitis to refer to the clinical syndrome of injury of the superficial digital flexor tendon, because clinical signs of inflammation are hallmarks and tendonitis is pertinent. We recognize that others prefer the term tendonopathy (see Chapter 68).

Superficial Digital Flexor Tendonitis in Racehorses

Superficial Digital Flexor Tendonitis in Racehorses

Joan S. Jorgensen, Ronald L. Genovese, and Mike W. Ross

Superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) injuries substantially compromise athletic performance and may culminate in a career-ending injury. The incidence of SDFT injuries in Thoroughbred (TB) racehorses ranges from 7% to 43%,1,2 and such horses are most at risk because of high racing speeds or high speeds associated with jumping (steeplechase racing, see Chapter 112).3 In National Hunt horses the prevalence of tendonitis of the SDFT as detected using ultrasonographic examination was found to be 24%.4 In that study a reference range of cross-sectional area (CSA) measurement was obtained (77 to 139 mm2), but ultrasonographic examination could not predict injury, and variation in prevalence among yards suggested that training methods may influence injury rate.4 Tendonitis is quite common in the Standardbred (STB) racehorse, more so in pacers in North America than in trotters (see Chapter 108). Other performance horses, including upper-level event horses (see Chapter 117), have an increased risk of SDFT injury (see page 721). Horses used for dressage (see page 725), high-level show jumpers (see Chapter 115 and page 724), racing Arabians (see Chapter 111) and Quarter Horses (see Chapter 110), polo ponies (see Chapter 119), and fox hunters incur SDFT injuries less frequently.3,5,6 SDFT injury from athletic use in racehorses commonly is seen because of repetitive speed cycles over distance and possibly genetic predisposition to SDFT injury.7 We are aware of several TB racehorse mares and at least one TB stallion and one STB stallion that are known to have progeny with an increased susceptibility to SDFT injury compared with the normal racehorse population. Additional factors that may predispose a horse to SDFT injury include conformation (see Chapters 4 and 26), working surfaces, shoeing, training methodology, and the relationship between the level of physical fitness and the current exercise.

SDFT injury also occurs spontaneously in sedentary or lightly used horses older than 15 years of age. These tendon injuries often are severe and generally involve the proximal metacarpal region and the carpus and extend to the musculotendonous junction in the antebrachium. Many of these injuries result in overt lameness, tendon thickening, and carpal sheath effusion (see Figure 6-18). Sometimes, however, the only clinical sign is lameness, which is often pronounced to severe, with little palpable thickening of the SDFT. Subtle swelling in the proximal aspect of the SDFT is easily missed, particularly when the limb is held in flexion. These injuries occasionally can be difficult to diagnose, requiring local analgesia and ultrasonography. Although older nonracehorses appear prone to the development of superficial digital flexor (SDF) tendonitis in the proximal metacarpal and palmar carpal regions, the condition is sometimes seen in older STB racehorses, usually pacers. In a recent study, only two of 12 nonracehorses with tendonitis of the proximal aspect of the SDFT returned to previous use with medical management; horses were significantly older (mean age of 18 years, median 17 years, and range 11 to 23 years) than a comparison group with tendonitis of the SDFT in the midmetacarpal region, and prognosis was significantly worse than in the same comparison group (10 of 22 horses with midmetacarpal SDF tendonitis returned to previous use after injury).8 In an unpublished study of 29 horses with tendonitis of the proximal aspect of the SDFT, mean age was 13 years (median 15, range 2 to 30 years), there were six racehorses and 23 nonracehorses of mixed use, lameness was generally pronounced, and ultrasonographic evaluation revealed injury that often involved the palmar carpal region from near the musculotendonous junction to the proximal metacarpal region.9 Overall, 14 of 24 horses (58%) became sound and returned to work, and five of seven horses managed surgically (desmotomy of the accessory ligament of the SDFT [ALSDFT],otherwise known as superior check desmotomy) in combination with carpal retinaculotomy and proximal metacarpal fasciotomy, or transection of the ALSDFT in combination with intralesional injections of fresh bone marrow) returned to work.9

Most injuries in the SDFT caused by athletic use occur in the midmetacarpal region (zones 2B to 3B), but injuries also occur at the musculotendonous junction of the antebrachium, in the carpal canal and subcarpal region, and in the pastern (see Chapter 82). The plantar hock region is the most common site of SDFT injury in hindlimbs, especially in the STB racehorse (see Chapters 78 and 108). SDF tendonitis in the hindlimb in the plantar tarsal region is referred to as curb and is one of the collection of soft tissue injuries comprising this injury (see Figure 4-30). Occasionally this injury extends into the midmetatarsal region. Infrequently, a subtle SDFT injury is associated with tenosynovitis of the digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS) in hunters, jumpers, and dressage horses. In the STB racehorse, tendonitis often extends to the distal metacarpal region, involving the DFTS and palmar annular ligament, and there is generalized soft tissue thickening in the palmar aspect of the fetlock region.

Substantial progress has been made in understanding the nature of tendon injury and the mechanisms of healing (see Chapter 68). Historically, tendon injuries have healed by the process of scar tissue formation and maturation, known as reparative healing. During repair, injured elastic tendon fibers are replaced with modified fibrous scar tissue, resulting in a tendon repair that is never totally normal. The quality of repair can vary greatly. Some tendon injuries repair and resolve with enough mature collagen so that they return to nearly normal size, with sufficient remodeling that approximately parallel alignment of the repair tissue results. Other injuries develop a scar, with an overall increase in tendon size, poor or random fibrous tissue alignment, and peritendonous fibrosis.

Many of the proposed therapeutic approaches are directed at maximizing the chances for a more physiologically functioning tendon. Therapy requires a multifaceted approach that reduces the acute inflammatory response and hemorrhage in the acute phase and improves fiber alignment during the long rehabilitation phase. The ultimate goal of any treatment and management program is to maximize the chances for a tendon to repair with adequate strength and elasticity for a return to a similar level of performance with the lowest risk of reinjury. Recently attempts have been made to heal equine soft tissue injuries using principles of regenerative healing. Regenerative healing occurs in fetal tissues and involves restoration of tissue without scar formation. Regenerative techniques involve the use of freshly harvested or cultured mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or other sources in an attempt to heal adult tissues in a manner similar to healing seen in a fetus (see Chapter 73). Improvement was reported in nine of 12 horses with SDF tendonitis injected with undifferentiated autologous MSCs, and the technique was found to be safe and efficacious.11 Reimplantation of autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs in 168 TB racehorses (National Hunt horses) with SDF tendonitis resulted in a substantially smaller reinjury rate (18%)12 than that previously reported (56%13).

Clinical Signs

Swelling

For assessing tendon injuries, swelling is defined as subcutaneous or peritendonous fluid accumulation. Digital palpation reveals a soft or semifirm, diffuse or focal fluid accumulation that may prohibit exact palpation of the SDFT. Subcutaneous swelling can be associated with tendon injury, especially in the acute stage of injury. Careful digital palpation of the limb held in a semiflexed position may reveal slight crepitus in an acutely injured tendon. However, subcutaneous inflammation or hemorrhage is not associated invariably with tendon injury. Examples of focal edema or hemorrhage without substantial SDFT injury include swelling associated with cording of the midmetacarpal region secondary to a malpositioned bandage or subcutaneous swelling in the proximal or distal metacarpal region caused by malpositioned tendon boots or stable (stall) bandages. An example of diffuse swelling is pitting edema (see Chapter 14), occasionally caused by external blistering. Diffuse filling also may reflect a subsolar abscess or cellulitis.

Sensitivity to Direct Digital Palpation

A painful response to direct digital palpation is often a reliable clinical test for tendon injury and may be the earliest clinical sign detectable (see Figure 6-15). Examination is best performed by holding the limb in a semiflexed position and palpating with the thumb and forefinger systematically from proximal to distal in the metacarpal region in an effort to elicit a painful response. When a sensitive area is palpated, the horse generally flinches. The examination has many caveats. If a sensitive response is elicited bilaterally, the horse may merely be hyperresponding to increased pressure and possibly has no injury. Not all horses with tendon injury have a painful response. Horses with blistering of the skin, adverse local drug reaction, infection, or cording are also hyperresponsive and more reactive than those with a tendon injury. In addition, extreme sensitivity to direct palpation coupled with focal or diffuse swelling may indicate a problem not related to the tendon.

Tendon Profile

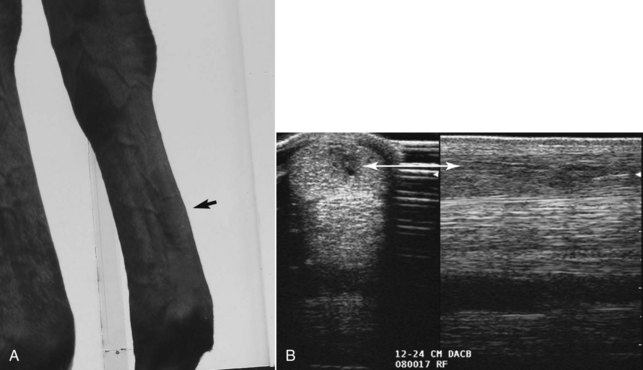

Evaluation of the tendon profile with the limb in a full weight-bearing position can provide valuable information. In a normal limb the metacarpal region has a straight palmar profile. A normal SDFT should be superficial and parallel to the DDFT. It is important to examine the profile from all possible angles. With a slight injury, the tendon often has a normal profile when viewed from the lateral aspect and a convex or bowed profile from the medial aspect, or vice versa. In fact, slight changes on tendon profile are often most obvious when examining the horse visually from the opposite side (Figure 69-1). It takes considerable damage to the SDFT to change the visually detected profile of the tendon, and ultrasonographic evidence of tendon injury is often much more pronounced than expected. In a horse with an acute total rupture, little swelling and thickening may be present if the leg is examined within 2 hours of the injury. However, with the limb in full weight-bearing position, one may note hyperextension of the metacarpophalangeal joint. In this case, digital palpation along the palmar aspect of the tendon reveals a 1- to 2-cm defect in the SDFT. Digital palpation with the limb in a semiflexed position also reveals laxity and excessive mobility of the tendon.

Swelling in the Distal Metacarpal Region

In horses with chronic tendonitis of the SDFT or in those with only tendonitis of the SDFT in the distal metacarpal region, there can be involvement of the DFTS and the palmar annular ligament (PAL). Chronic, distal metacarpal tendonitis of the SDFT in the region of the PAL is common in STB racehorses, polo ponies, and older TB racehorses (Figure 69-2). It is important to differentiate clinical syndromes in this region. In horses with chronic tendonitis of the SDFT, the primary lesion is the tendon injury with subsequent restriction of movement through the “fetlock canal” (reduced gliding function) by the PAL. Thus the PAL is not primarily involved but is merely a “passenger” in the clinical syndrome. In these horses palmar annular desmotomy is critical to restore gliding function and to decompress the swollen SDFT, but there is no actual palmar annular desmitis. Primary palmar annular desmitis, tenosynovitis of the DFTS, and deep digital flexor (DDF) tendonitis are other clinical syndromes that cause swelling in the distal, palmar metacarpal region and should be differentiated from distal SDFT lesions and compression by the PAL (see later discussion and Chapters 70 and 74).

Tenosynovitis of the Carpal Sheath or Digital Flexor Tendon Sheath

Tenosynovitis may be associated with a tendon injury or may be a clinical entity without tendon injury (see Chapters 74 and 75). Ultrasonographic evaluation is required to appreciate tendon injury in the presence of tenosynovitis.

Tendon Injury Limited to the Pastern

Injury to one or both of the SDFT branches of the pastern is generally but not always associated with branch thickening and a painful response to direct digital pressure (see also Chapter 82). This is best appreciated with the limb held in a semiflexed position and direct pressure placed on the branch with the clinician’s thumb. Injury to the SDFT branch(es) may be associated with tenosynovitis. Injury to the branches of the SDFT should be carefully differentiated from injuries of the distal sesamoidean ligaments.

Management of the Acute Phase of Tendon Injury in Racehorses

In most horses with subtotal SDFT injuries in the acute phase, antiinflammatory and supportive management is instituted. A variety of treatment regimens are available. For the most part, systemic nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as phenylbutazone (4.4 mg/kg/day) for 7 to 10 days and a single dose of systemic corticosteroids such as dexamethasone (0.04 mg/kg) are included in the initial therapy. Perilesionally administered corticosteroids are considered contraindicated in horses with tendon injuries, especially long-term use, because these drugs are thought to delay collagen formation. However, some clinicians use a single perilesional dose of triamcinolone acetonide (6 to 9 mg) or methylprednisolone acetate (40 mg) (dystrophic mineralization occasionally has been associated with methylprednisolone therapy) in horses with slight, peripheral tendon injuries in STB racehorses, especially when associated with curb (see Chapter 78). Practitioners often administer a course of polysulfated glycosaminoglycans (PSGAGs; 1 vial per week for 4 weeks) in the acute stage.

Injury Assessment and Goals for an Athletic Outcome

Qualitative assessment combines the physical findings and a subjective ultrasonographic appraisal. This gives an accurate diagnosis, but we also strongly encourage the use of quantitative ultrasonographic evaluation. This includes data such as CSA and echogenicity and fiber alignment scores (see Chapter 16).

Ultrasonographic Evaluation and Categorization of Injuries

The acquisition and assessment of accurate ultrasonographic data require high-quality images, and it is important to develop a rigid, standardized technique (see Chapter 16). The ultrasonographer must take primary responsibility for image interpretation. For a second person to give an opinion on images previously obtained by someone else is often difficult.

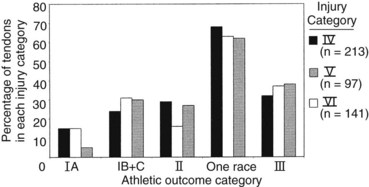

Quantitative ultrasonographic data include CSA, percentage of CSA occupied by a lesion, grade of echogenicity of a lesion (type or echo score [TS]), and assessment of fiber bundle alignment in longitudinal images (fiber alignment score [FAS]). Each of these data points is assessed at every defined level of the limb (zone), and they are then summed to provide total scores. These scores then can be used to categorize an injury as minimal (category III), slight (category IV), moderate (category V), or severe (category VI) (see Chapter 16). The following comments apply to forelimb and hindlimb injuries, although reference is made to only the metacarpal region.

Subacute Phase Treatment and Long-Term Rehabilitation

History of Treatment in Racehorses

A comprehensive retrospective study of TB and STB racehorses currently is being performed to compare the rate of return to racing among a variety of therapeutic regimens for minimal (category III), slight (category IV), moderate (category V), and severe (category VI) tendon injuries documented by ultrasonography. Therapies include pasture turnout, external blistering, internal blistering, intralesional therapies (excluding β-aminopropionitrile fumarate [Bapten]), or a combination of these. In addition, the amount of layup time is being considered for each category of injury. If all therapeutic regimens are combined (Figure 69-3), preliminary data indicate that few racehorses successfully return to racing without reinjury (athletic outcome I, completed five or more races), especially with severe injuries.14 In addition, these data demonstrate that few racehorses are able to return to racing and not experience reinjury of the SDFT, sustain injury to the contralateral SDFT, or injure the suspensory apparatus (subcategories IB and IC). Ultimately, we hope that this research helps to determine optimum therapy for specific lesions and better equip the veterinarian to provide accurate prognostic information.

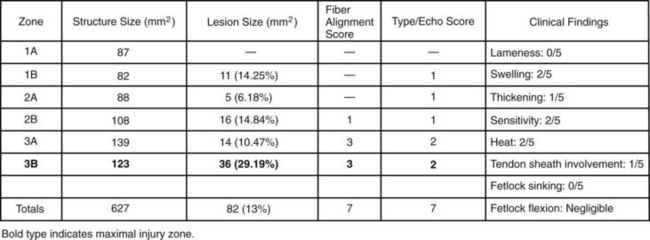

Symptomatic Treatment with Continued Exercise

Consider a 3-year-old TB gelding racehorse with a swollen left front SDFT after a race (Figure 69-4). Quantitative ultrasonographic analysis revealed a total lesion area of 13%, TS of 7, and total FAS of 7, indicating a mildly injured (category IV) tendon. The horse was treated symptomatically with antiinflammatory medication and continued to race. After  months and six races the horse was racing well, having earned more than $34,000. After two additional races, the total lesional area increased and the horse’s performance decreased. Long-term therapy with time off was instituted. STB racehorses are generally more successful than TBs in continued performance with a tendon injury.14

months and six races the horse was racing well, having earned more than $34,000. After two additional races, the total lesional area increased and the horse’s performance decreased. Long-term therapy with time off was instituted. STB racehorses are generally more successful than TBs in continued performance with a tendon injury.14

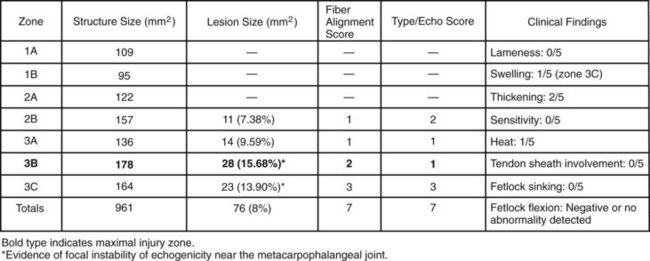

Ultrasonographic evaluation is used to monitor tendon stability during training. For example, ultrasonographic examination of a right front SDFT  months after the baseline scan and after 6 weeks of galloping indicated stable total CSA values but increased hypoechogenic tendon fascicles in zones 3B and 3C (Figure 69-5). Clinically, increased heat and swelling in the distal metacarpal region were found, which indicated tendon instability at the current exercise level and a high risk of reinjury with continued training. The trainer was unwilling for economic reasons to pursue another long-term treatment program and decided on an intermediate program of 30 days of ponying (leading the horse from another horse) and swimming. Six weeks later substantial reinjury of the SDFT occurred in the distal metacarpal region (Figure 69-6). Use of serial ultrasonographic monitoring is discussed in detail elsewhere (see Chapter 16).

months after the baseline scan and after 6 weeks of galloping indicated stable total CSA values but increased hypoechogenic tendon fascicles in zones 3B and 3C (Figure 69-5). Clinically, increased heat and swelling in the distal metacarpal region were found, which indicated tendon instability at the current exercise level and a high risk of reinjury with continued training. The trainer was unwilling for economic reasons to pursue another long-term treatment program and decided on an intermediate program of 30 days of ponying (leading the horse from another horse) and swimming. Six weeks later substantial reinjury of the SDFT occurred in the distal metacarpal region (Figure 69-6). Use of serial ultrasonographic monitoring is discussed in detail elsewhere (see Chapter 16).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

months after the baseline scan and 6 weeks after galloping was resumed. Before galloping, the total cross-sectional area was 975 mm2, which decreased to 961 mm2. However, new hypoechogenic lesions were documented in zones 3B and 3C, indicating an unstable healing process.

months after the baseline scan and 6 weeks after galloping was resumed. Before galloping, the total cross-sectional area was 975 mm2, which decreased to 961 mm2. However, new hypoechogenic lesions were documented in zones 3B and 3C, indicating an unstable healing process.