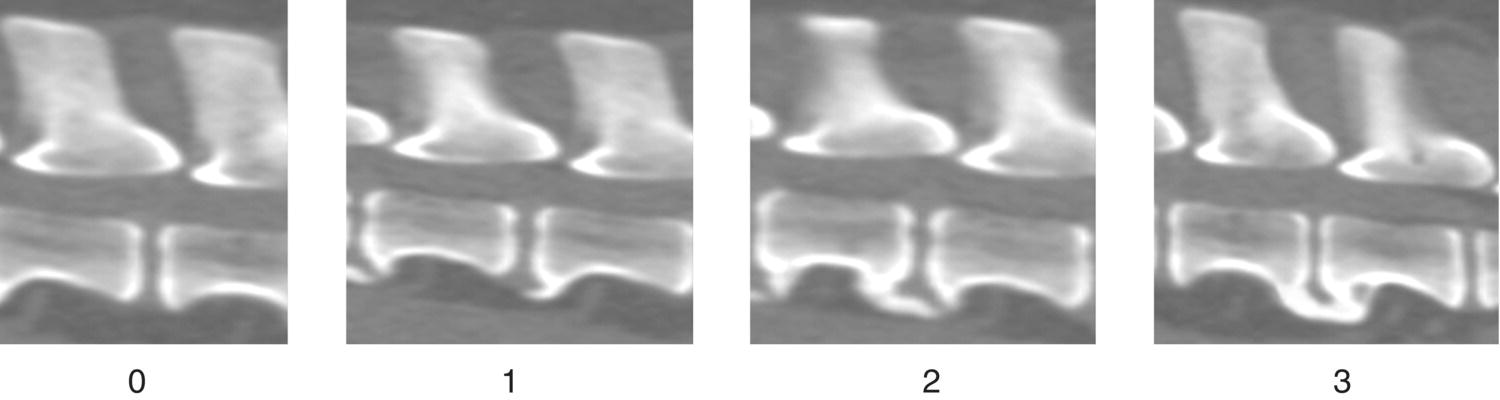

8 William B. Thomas and James M. Fingeroth Several disorders are characterized by new bone formation on the spine of people and animals, including spondylosis deformans, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), and osteoarthritis of the facet joints. The nomenclature of these disorders is confusing for several reasons. The terms used to describe these conditions have often been used indiscriminately rather than adhering to precise diagnostic criteria. For example, in the past, the term spondylosis deformans was sometimes used to also refer to what is more properly called DISH. Another example is that clinicians may interchange the terms “spondylitis,” which indicates an inflammatory condition, and “spondylosis,” which is not inflammatory. Finally, it is not certain that the canine diseases are always identical to those in human patients. Another point of confusion relates to the tendency to erroneously attribute a patient’s clinical signs to one of these conditions when in fact the patient is suffering from an unrelated spinal lesion. This arises because the new bone formation is often so obvious and sometimes even dramatic on radiographs. On the other hand, more clinically significant lesions such as intervertebral disc herniations result in subtle changes on plain radiographs and may not even be apparent without more advanced imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Spondylosis deformans is a noninflammatory condition characterized by the formation of bony projections at the location where the annulus fibrosus is attached to the cortical surface of adjacent vertebral bodies (Sharpey fibers). Although these bony growths are often referred to as osteophytes, true osteophytes occur at the osteochondral junction of synovial joints. The correct term for the bony proliferation in spondylosis deformans is enthesophyte [1]. These enthesophytes are located several millimeters away from the junction between the disc and the vertebra (Figure 8.1). They typically expand ventrally and laterally but not dorsally. Enthesophytes vary from small spurs to bony bridges across the disc space leaving at least part of the ventral surface of the vertebral body unaffected. Spondylosis deformans can be classified as follows (Figure 8.2) [2, 3]: Figure 8.1 Spondylosis deformans. Enthesophytes are located on the ventral aspect of the vertebral body, several millimeters away from the junction between the disc and the vertebra. Figure 8.2 Grades of spondylosis deformans. Grade 0: no enthesophytes. Grade 1: small enthesophyte at the edge of the epiphysis that does not extend past the end plate. Grade 2: enthesophyte extends beyond the end plate but does not connect to enthesophyte on the adjacent vertebra. Grade 3: enthesophytes on adjacent vertebrae connected to each other forming radiographic bony bridges between vertebrae. While the exact pathogenesis of spondylosis deformans is unclear, changes in the peripheral fibers of the annulus appear to be the most important inciting cause. In most cases, age-related breakdown of the peripheral annular fibers (Sharpey fibers) lead to discontinuity and weakening of the attachment of the disc to the vertebra. This leads to stress on the ventral longitudinal ligament where it attaches to the vertebral body. Enthesophytes develop at the stressed area and grow by a process of endochondral ossification. Bone growth extends ventrally and then laterally but rarely dorsally, probably because of the differences in the attachments of the ventral and dorsal longitudinal ligaments and the ventral and dorsal attachments of the annulus and vertebral bodies [4]. Spondylosis deformans can also develop subsequent to other causes of disc injury, such as spinal trauma, ventral slot surgery, or discospondylitis. With regard to the latter, this is often a point of confusion for clinicians, with occasional misinterpretation of noninflammatory spondylosis with the inflammatory (usually infectious) lesions in the disc space seen with discospondylitis. This is addressed further in Chapter 20. This confusion is sometimes compounded by the fact as noted previously that discospondylitis, because of its degradative effect on the disc and end plates, usually induces spondylosis (i.e., enthesophytes on the involved adjacent vertebrae). Hence, radiographic interpretation requires the clinician to distinguish between benign spondylosis from that which has resulted from inflammatory destruction of the intervertebral disc. Spondylosis deformans is common in dogs, with the reported incidence varying depending on the age and breed distribution of the studied population and the method of diagnosis [4]. It is uncommon in dogs less than 2 years of age and after that the prevalence and the grade of spondylosis increase with age. By the age of 9 years, approximately 25–70% of dogs are affected [5, 6]. Large-breed dogs are at increased risk but any size dog can be affected [3, 5, 7]. The prevalence of spondylosis deformans is especially high in boxers (approximately 40–85%, depending on age), and a genetic predisposition has been identified in this breed [2, 3, 7]. The L7–S1 disc space is most commonly affected with the thoracolumbar region (T12–L3) being the next most commonly affected level. Affected patients often have multiple sites of involvement [5, 7, 8]. Spondylosis in the cervical region is less common. Spondylosis deformans is also common in cats, and as with dogs, the prevalence increases with age [6, 9]. Spondylosis deformans is usually an incidental finding, and there is no clear correlation between the presence of spondylosis and clinical signs of spinal disease [5, 8]. In two studies, there was no significant difference in pain, lameness, or neurologic deficits in dogs with spondylosis compared to dogs without spondylosis [10, 11]. This is similar to lumbar spondylosis in people, where the frequency of signs or symptoms among individuals with enthesophytes is no greater than among those individuals without enthesophytes [12]. Bony spurs typically do not expand into the vertebral canal and therefore do not compress the spinal cord to cause neurologic deficits (Figure 8.3

Spondylosis Deformans

Spondylosis deformans

Pathophysiology

Clinical features

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree