Chapter 28 Soft Tissue Surgery

As members of the Myomorph group of rodents, hamsters, gerbils, rats, and mice share similar anatomy. Rats and mice are murid rodents, whereas gerbils and hamsters are cricetid rodents. All are monogastric, have a bicornuate uterus and uterine body, and have testicles that are large relative to their body size and usually descended into a large, well-developed scrotum, which, however, can easily be retracted into the abdomen through relatively large inguinal canals. The spermatic cords can be palpated cranial to the penis on each side as they exit the inguinal canal. Caudally, within the scrotum, the testicles are separated by the median raphe. The female reproductive tract is more like that of dogs and cats than rabbits and hystricomorph rodents. The mesovarium is short, making it difficult to exteriorize the ovaries for removal. The uterine body is relatively short, with a single cervical os. The oviducts encircle the ovaries, as they do in other rodents. This group of rodents is sexually mature at 40 to 60 days of age.23 Rats and mice have a long, hairless tail; gerbils have a long, haired tail; and hamsters have a short, lightly haired tail. Hamsters have large cheek pouches in which they store food.

Presurgical Considerations

Patient Support

A preoperative database should include a complete blood count (CBC), plasma biochemical analysis, urinalysis, and whole-body radiographs, especially to evaluate the lungs, because they are especially prone to asymptomatic respiratory disease as well as to renal disease. Rats and mice frequently have subclinical mycoplasmal pneumonia. Although renal disease is common in older rodents, it can be difficult to obtain urine in a small rodent. Because they urinate frequently, however, one can put the rodent in a clean, dry, plastic or glass container, and a few drops of urine can then be collected from the container within a few minutes. This is all that is required to evaluate the urine by dipstick and determine the specific gravity. Proteinuria and dilute urine suggest underlying renal disease. At the very least, a preoperative database should include a packed cell volume, total protein, urine specific gravity, and a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) estimate by an azotemia test strip. These tests require only a few drops of blood and one drop of urine.

Rodents are physiologically unable to vomit, so a prolonged fast is not necessary.35 They also have relatively low hepatic glycogen stores and are prone to developing hypoglycemia during a prolonged fast.16,35 A short fast of 1 hour will allow the animal to clear food material from its mouth for oral procedures or to minimize the risk of an endotracheal tube carrying food into the trachea if intubation is anticipated. Administration of fluids containing dextrose (SC, IV, or IO) will help combat loss of energy stores. A prolonged fast has not been shown to decrease the volume of abdominal contents in these hindgut cellulose-fermenting species.

Rodents have a large body surface area/volume ratio predisposing to the development of hypothermia during long anesthetic and surgical procedures. A temperature monitoring probe is ideal for continuous evaluation of core body temperature. The body temperature of a rat can drop 18°F (10°C) after 20 minutes of anesthesia.17 Hypothermia decreases the metabolism and excretion of many anesthetic drugs. A short operative time—accomplished by having all the necessary equipment ready and accessible—will help to minimize the development of hypothermia. Alcohol should be avoided for skin preparation because the evaporative cooling will potentiate the development of hypothermia. Warm, sterile saline is as effective as alcohol in patient preparation. Alcohol is also flammable and can ignite if electrosurgery or laser is used. A circulating warm-water blanket under the patient should be set at 104°F (40°C), because these patients have a higher resting body temperature than dogs and cats. Forced warm air blankets (Bair Hugger, Arizant, Eden Prairie, MN) are also useful in combating hypothermia. The Thermally Controlled Surgery Pad (RICA Surgical Products, Inc., Schiller Park, IL) is a safe plastic pad placed under the patient that does not overheat and turns on automatically when a patient is placed on it and turns off automatically when not in use. Also, the Hot Dog Warming System (Augustine Biomedical & Design, Eden Prairie, MN) is a safe and effective conductive-fabric warming unit. Other sources of supplemental heat, including hot water bottles or examination gloves filled with warm water and radiant heat lamps, can cause thermal burns and must be used with caution. Placing a towel between the heat source and the patient does not ensure safety. Closely monitor all heat supplement devices to avoid accidentally burning the patient. The patient should be draped as quickly as possible because the drape will help hold in heat.

Seemingly small amounts of hemorrhage can be disastrous in such small patients. Although it may not be practical, ideally it is best to have blood from a conspecific available for transfusion when significant blood loss is anticipated. Strict attention to hemostasis is vital. The average cotton-tipped applicator holds approximately 0.1 mL of blood when completely soaked. Loss of 10% to 15% of the total blood volume (approximately 1% of body weight) is usually safe. Loss of more than five cotton-tipped applicators full of blood (0.5 mL, or 10 drops) in a 50-g mouse is equivalent to more than 20% of the blood volume and is potentially dangerous.16 Approximately 1.2, 1.4, and 4.0 mL of blood is equivalent to more than 20% of the blood volume (a potentially dangerous amount to lose) in the average-sized gerbil, hamster, and rat, respectively.16 Intravascular fluid volume may also be supported with the aid of crystalloid fluids such as lactated Ringer’s solution with or without dextrose. Intraosseous cannulas such as spinal needles are commonly inserted in a normograde fashion into the proximal femur or proximal tibia of pet rodents in a manner analogous to normograde insertion of an intramedullary pin for fracture management. This provides access to the vascular system for fluid support and emergency drug therapy if needed. Fluids may also be administered subcutaneously or intraperitoneally with slower absorption. These routes are not acceptable for treating animals that are seriously ill, severely dehydrated, or in shock. The standard recommendation for IV fluid support during anesthesia and surgery is 10 mL/kg per hour; however, a single dose of 10 mL/kg SC of 4% dextrose has been recommended for short procedures in rodents.35

The thoracic cavity of many small rodents is small relative to their body size. Placing the patient in dorsal recumbency can compromise respiration because of the pressure of the abdominal viscera on the diaphragm. Tilting the patient so that the viscera are displaced caudally may be beneficial for the respiratory system of the anesthetized patient.35 Securing the patient to a restraint board such as the Thermally Controlled Surgery Pad (Fig. 28-1) rather than the surgical table allows the patient to be tipped in any direction and to be easily repositioned intraoperatively.

Instrumentation

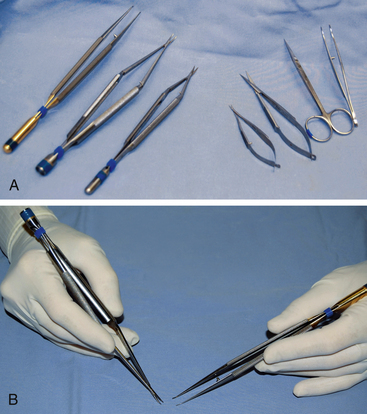

In general, ophthalmic instruments are not suited to surgery in small mammals (Fig. 28-2). The short length of the instruments makes them difficult to control and manipulate the tissues within the body cavity. Microsurgical instruments are constructed so that only the tips are miniaturized, which is different from ophthalmic instruments, where the whole instrument is miniaturized.4 The handles should be of normal length (5.5 to 7 in.) to help provide stability to the tips, thus diminishing the effects of tremors. The tips of the instruments should extend beyond the fingers far enough to use within the patient’s body cavity, while ophthalmic instruments may be used for surface work. The handles should be round to facilitate the required rolling action between the thumb and first two fingers. Round handles are most important for the needle holders, where a curved needle must be rolled through the tissue. Many prefer needle holders without a clasp or box lock because the motion that occurs when the lock is set and released may cause the needle to tear tissues. Hold a microsurgical instrument as if you were holding a pen. An across-the-palm grip is inappropriate and limits the function of these precision instruments (see Fig. 28-2).

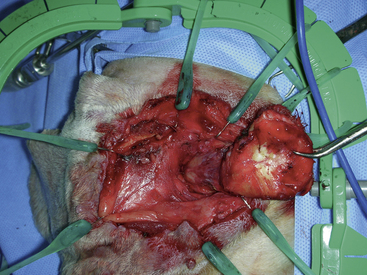

A microsurgical pack should consist minimally of a microsurgical needle holder (Micro Surgery Needle Holder, straight, T/C without lock, 8 in.; Micro Surgery Needle Holder, curved, without lock, 7.125 in., pencil-style grip), microsurgical scissors (Tew-Barraquer Scissors, curved, 7 in.), and microsurgical thumb forceps (Micro Surgical Forceps, curved, 7 in., pencil-style grip) (all from RICA Surgical Products, Inc., Schiller Park, IL). Many microsurgeons use jeweler’s forceps as microsurgical forceps (Long Jeweler’s Forceps No. 3, RICA Surgical Products, Inc.). These are significantly less expensive and serve their purpose adequately, but they are not ideal. They have sharp tips, are short, and do not have round handles. I prefer curved ring-tipped microsurgical forceps (Ring Tip Forceps, Cat. No. 843025, RICA Surgical Products, Inc.) and Counterweight Round Handle Ring Tip Tissue Forceps (Cat. No. 2200-260, Sontec Instruments, Centennial, CO) because they are of a standard length, counterbalanced, and delicate, but the tips have rings that distribute the pressure over a wider surface, making them less traumatic for tissue handling while one can still hold the fine strand of suture for knot tying (Fig. 28-3). Eyelid retractors do not work well in small rodents because the tension cannot be adjusted to fit the individual patient. Heiss and Alm Self Retaining Retractors (RICA Surgical Products, Inc.), analogous to Bennett and Doolan retractors (Sontec Instruments), respectively, work well as abdominal and tissue retractors in small rodents. The Lone Star Retractor (Veterinary Specialty Products, Inc., Mission, KS) consists of Silastic bands with tissue hooks on the ends and a plastic frame (Fig. 28-4). All components are fully autoclavable and quite durable. The stay hooks are placed in the tissue and the Silastic bands inserted into the notches of the frame to maintain tissue retraction. Use the least amount of tension necessary to maintain exposure. Hemostatic clips (Hemoclips and Samuels Hemoclip Applier, 6.25 in., RICA Surgical Products, Inc.) are also very useful and available in five sizes, with small and medium being most applicable for pet rodent surgery. A microsurgical pack can be put together for $1,500 to $2,000. After experience has been gained, other microsurgical instruments such as micro mosquito hemostats may be added to the pack.

Magnification

SurgiTel (General Scientific Corp., Ann Arbor, MI) eliminates most of the problems associated with the hobby loupes (Fig. 28-5). It is ergonomically engineered to be used with a proper neck posture, the lenses do not cover the entire visual field so the surgeon is not committed to looking through the lenses, it has a focal LED light source, and the lenses also have a focal range, rather than a set focal distance, which generally allows the entire patient to be in focus during surgery.

Focal Light

General Scientific Corp. also offers SurgiCam, a digital video camera with 3× magnification that mounts over the lenses. This system allows the procedure to be viewed on a monitor. It makes still photos or video recordings that can be edited—a useful client education tool.

Hemostatic Aids

The Surgitron Dual Frequency 120 (Ellman International, Inc., Hewlett, NY) radiowave energy is emitted at 4.0 MHz, providing control of absorption depth in tissue and resulting in minimal cellular damage and heat conduction (Fig. 28-6). This unit features a unique isolated circuitry system that maintains a constant frequency of 4.0 MHz. With this constant frequency, there is only 15 μm of lateral heat damage compared with 90 μm from the older Surgitron units and more than 100 μm with a carbon dioxide laser. Standard electrosurgical units generally produce more than 750 μm of lateral heat damage.

Patient Preparation

Standard aseptic technique is essential with pet rodent patients. Rodents are susceptible to infections and their cages often require them to be in close proximity to their urine and feces. Be careful to avoid damaging the skin during preparation for surgery. The area clipped should be minimized to help control heat loss. A No. 50 clipper blade (Oster Professional Products, McMinnville, TN) is ideal for fine, thin hair in patients with thin skin, such as small rodents. The teeth are closer together than those of the No. 40 blade, making it less likely that the patient’s skin will get caught between the teeth and be cut accidentally. Clear plastic drapes allow respiration to be monitored during the procedure. A plastic drape with a 3.5- × 5-in. adhesive center and an overall size of 40 × 54 in. is commercially available (Veterinary Transparent Surgical Drape, Veterinary Specialty Products, Inc.). This allows the surgeon to maintain a sterile field over the entire table and still monitor the patient. A smaller drape (24 × 24 in.) is also available for minor procedures but is not large enough to create a sterile field on a surgical table. These drapes may also hold heat better than cloth or paper drapes. Place the four quarter drapes around the patient rather than the proposed incision, then place the plastic drape over the patient to cover the entire table and create a sterile field.

Orchidectomy

The primary indication for orchidectomy in rodents is to prevent breeding, as it is easier to castrate males than to spay females. Urethral plugs have been described in male rats, gerbils, golden hamsters, mice, and guinea pigs as a normal finding, although they have caused urethral obstruction in rats and mice.27 They are present in all healthy adult male rats, but their size decreases by 99% following orchidectomy. Urethral plugs are composed of proteins I-V from the seminal vesicles mixed with vesiculase, from the coagulating glands; these congeal to form the plug.6 Because orchidectomy virtually eliminates the risk of a urethral plug causing obstruction in rodents, some recommend routine orchidectomy at a young age for rats.

Whether it has an effect to suppress aggressive behavior is a subject of debate and there is no scientific evidence that orchidectomy will ameliorate aggression. In most species, orchidectomy is recommended prior to puberty because often, once sexual behaviors manifest, they become learned behaviors not necessarily affected by the loss of hormones. Testicular tumors, such as Leydig cell tumors, occur in rodents, especially rats, and orchidectomy is indicated for treatment. The incidence of testicular tumors varies with strain of rat and increases with age. Although testicular tumors are usually bilateral and multilobulated, unilateral tumors are generally very large, with the unaffected testis becoming atrophied. Leydig cell tumors are benign but can get quite large.41 Prostatic and testicular tumors are also reported in gerbils.41 Orchidectomy is indicated to prevent or treat these conditions.

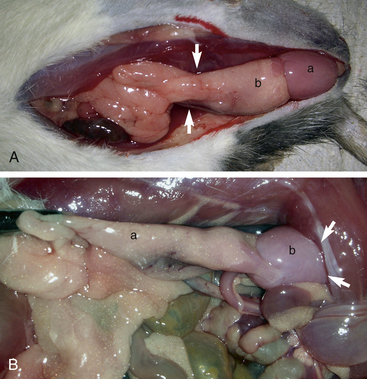

The procedure for orchidectomy in rats, mice, hamsters, and gerbils is similar. The testicles are located caudoventrally in the inguinal area and are readily retracted into the abdomen (Fig. 28-7). They can easily be pushed back into the scrotum with gentle rolling pressure on the caudal abdomen in a caudal direction just cranial to the pubis. The testicles are relatively large and contained in a well-defined scrotal sac caudal to the penis. The epididymal (testicular) fat is responsible for preventing intestinal herniation.23 This fat extends into the abdominal cavity near the kidneys bilaterally (Fig. 28-8). The fat, along with the testicular artery and vein, passes through the inguinal canal into the scrotum. It can be challenging to remove the testicle without removing or damaging the epididymal fat at the proximal end of the testicle and attached to the head of the epididymis. In performing a closed orchidectomy, removal of the entire testicle but leaving as much of the epididymal fat as possible avoids the risk of herniation or evisceration; however, the risk of this has not been clearly documented. Alternatively, the vaginal tunic can be ligated closed proximally after an open orchidectomy is performed with minimal trauma to the epididymal fat. Preservation of this fat appears to be important for preventing visceral herniation following open or closed orchidectomy in small rodents.

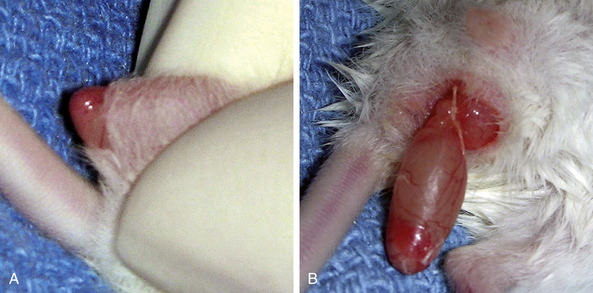

In small rodents there is little hair on the scrotum itself; however, adjacent to the penis on each side and cranially into the inguinal region, clip the fur with a No. 50 blade and perform a standard surgical preparation of the scrotum. Isolate the penis and scrotum and make a single transverse 0.5- to 1.0-cm incision at the distal (caudal) tip of the scrotum. Alternatively, two incisions oriented dorsal to ventral can be made, one in each side of the scrotum at the tail of the epididymis. Place the incision as far dorsally as possible to minimize postoperative incisional contamination by the cage substrate (Fig. 28-9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree