Chapter 21 Soft Tissue Surgery

Equipment

Little specialized equipment is required for surgery in rabbits. Appropriately sized Cole-style endotracheal tubes and a short, narrow laryngoscope or an open-style otoscope and a rigid plastic catheter are helpful for intubating the rabbit (see Chapter 31 for other intubation techniques). Equipment to monitor heart rate should be capable of measuring rates of 250 to 300 beats per minute. A heated surgery table or circulating water blanket, a source of radiant heat at locations where the patient is anesthetized, and a device to accurately monitor body temperature are necessary during long procedures on small patients.

Small (human infant) Balfour retractors, flexible hook retractors (Lone Star Retractor, Lone Star Medical Products, Stafford, TX), or chess piece retractors (CHESS Surgical System, Canica, Ontario, Canada) enhance abdominal exposure, and malleable retractors serve well to hold viscera out of the way without removing them from the abdomen. An assortment of sterilized stainless steel spoons of various sizes is helpful in removing the stomach contents during gastric exploratory surgery; vascular clamps, hair clips (hair-control clips), or bobby pins substitute for Doyen forceps, and mechanical suction is helpful for removing pus from dental abscesses and for surgery of the gastrointestinal tract. Skin staples work well for skin closure and cannot be removed by most rabbits.

Presurgical Treatment

The author provides food (grass hay) and water to rabbits up until the time of surgery, although some authors have suggested that a large volume of food in the rabbit’s stomach can cause variations in anesthetic doses.12 Begin antibiotic therapy in rabbits with systemic or localized bacterial infections, such as those with upper respiratory tract infections caused by Pasteurella species (“snuffles”) or with dental abscesses or infected wounds. Prophylactic antibiotics may be given if there is a significant chance of bacterial contamination during surgery. Quinolones, azithromycin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfa combinations, and sulfa drugs generally do not negatively affect the normal cecal-colic microflora of rabbits. Use caution with beta-lactams, other macrolides, and other antibiotics that target gram-positive or anaerobic bacteria.

Rabbits are considered steroid-sensitive species,4 and steroids are administered only if indicated by the underlying disease process; they usually are not given for routine or elective surgery. Give atropine when indicated (0.1-0.2 mg/kg SC, IM; see Chapter 31) or glycopyrrolate (0.01-0.02 mg/kg SC) to control bradycardia, salivation, or respiratory secretions. These problems are rare when isoflurane anesthesia is used. Some rabbits produce atropine esterase; in such cases the dose of atropine may have to be repeated if signs recur.

Postsurgical Monitoring

Blood Loss

The blood volume of the rabbit is reported to be approximately 57 mL/kg body weight.16,18 Most mammalian species experience a drop in arterial pressure and cardiac output with moderate blood loss. Loss of 15% to 20% of the total blood volume causes massive cholinergic release, with tachycardia and intense arterial constriction; thus blood is redistributed away from the gut and skin. In a 4-kg rabbit, this amounts to 34 to 45 mL of blood. An acute blood loss of 20% to 30% of total blood volume, or 45 to 68 mL in a 4-kg rabbit, is critical.

Pain and Analgesics

The very nature of rabbits is the foremost argument for the use of analgesics. A rabbit in pain is inactive, anorectic, and poorly responsive, and it may grind its teeth. Pain is assumed based on anthropomorphic evaluation of the injury or surgery the animal has experienced. See Chapters 31 and 41 for suggested dosages of analgesics.

Surgical Techniques

Adhesion Formation

Problems resulting from adhesions are regularly found in rabbits; these are most often reflected in postoperative problems involving the cecum, colon and bladder and result from adhesions to the uterine stump, broad ligament, or ovarian pedicle. Adhesions associated with gastrotomy, enterotomy, and a variety of other types of gastrointestinal surgery may also occur. Symptoms include recurrent cystitis, cystic calculi, and microurinary calculi.14

Prevention of adhesions has been the subject of much study, often involving rabbits as animal models of human disease.6,7 A large number of substances have been used to combat adhesion formation, but the majority of these have proven to either be too toxic for use, to possess a high a complication rate, to be too difficult in application, or simply not to work. Promising substances include hyaluronic acid solutions10 and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose.5 Chondroitin sulfate20 has also been reported to be effective. These agents act by mechanical separation of surfaces as well as adding a protective “finish” to the viscera. Both mechanisms being a feature of their inert nature.

Thrombolytics, such as streptokinase,13 have been reported to be effective in adhesion prevention, but they present difficulties with local and systemic administration and the risk of hypersensitivity. There have been several studies using recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) in rabbits.3,19 In a rabbit adhesion model, rt-PA was found to reduce the primary and recurrent adhesion rates by 80%.3 Use of rt-PA was shown to be safe in the presence of colonic anastomoses and did not alter abdominal wound strength or increase postoperative hemorrhage.

Other studies have evaluated the use of endoscopy to correct adhesions as compared with traditional laparotomy.23 These have shown that laparoscopic adhesiolysis is associated with a significantly reduced formation of new postoperative adhesions as compared with laparotomy.

Choice of Suture Material

The biologic and physical characteristics of suture material influence wound healing. New suture material made from polymers that are removed by hydrolytic degradation are much less reactive and cause fewer and weaker adhesions. For example, monofilament polyglyconate (Maxon, Davis & Geck, Manati, PR) or other similar monofilament synthetic suture for closure of gastrotomy, enterotomy, or colotomy sites, cesarean sections, or other major abdominal surgery are excellent choices. Stainless steel or tantalum clips (Hemoclip, Weck, Research Triangle Park, NC) are excellent for vessel and small pedicle ligation with minimal tissue reaction. A study of laser anastomosis for sutureless closure of the colon of rabbits has been published,15 and this technique holds potential for the future.

Skin Closures

Rabbits commonly remove skin sutures. All but the smallest rabbits will chew sutures of nylon or even stainless steel monofilament. Intradermal closures work very well but are time-consuming to place because of the tenuity of rabbit skin. Cyanoacrylate tissue cement (Vet-Bond, 3M Medical-Surgical Division, St. Paul, MN) works well to hold rabbit skin but is often removed by the rabbit. Skin staples are both reliable and well accepted by rabbits and their owners.

Common Procedures

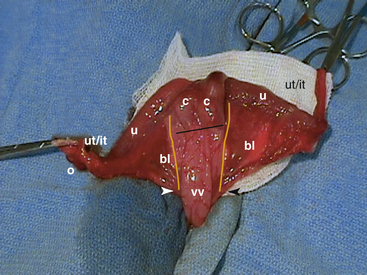

Ovariohysterectomy

The reproductive tract of the female rabbit is unusual compared with that of the dog or cat (Fig. 21-1). The uterus is bicornate. Each uterine cornua possesses a cervix (there is no uterine body). At maturity it is coiled in the caudal abdomen, cranial and just dorsal to the urinary bladder. Long uterine (tuba uterina) and infundibular tubes (infundibulum tubae) extend between the cornua and the ovary.21 The uterus is easily exteriorized but is more fragile than that of other species. In a healthy doe, the caudal portion of the broad uterine ligament (ligamentum latum uteri), the mesometrium, is a principal fat-storage site that makes identifying and ligating uterine vessels difficult. The urethra of the female rabbit empties into the proximal end of a deep vaginal vestibule. Expression of the bladder with the animal in dorsal recumbency often leads to retrofilling of the vaginal vault. This can be a source of contamination of the peritoneal cavity during uterine surgery. It is also important not to confuse the vaginal vault with the bladder.

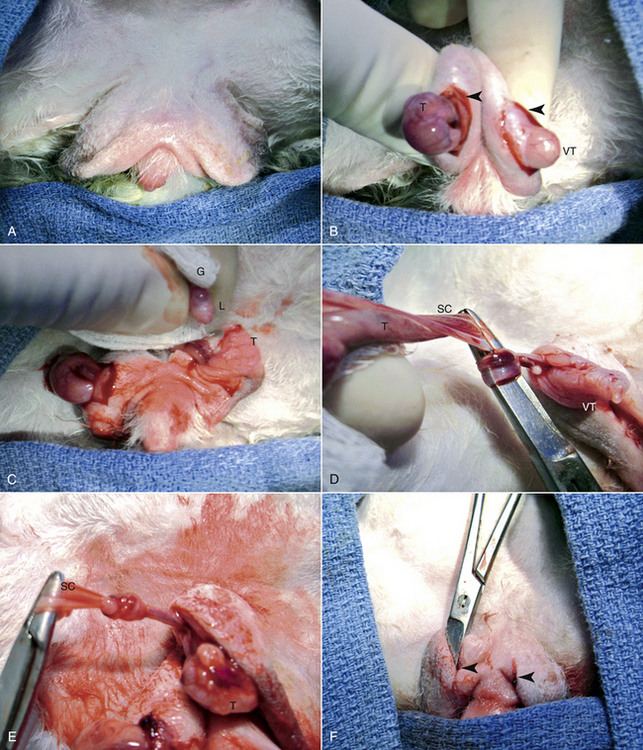

Orchidectomy (Castration)

For castration, anesthetize and restrain the buck in dorsal recumbency. Carefully shave the hair from the scrotum and surrounding area and surgically prepare and drape the area to minimize contamination. Make a 1- to 1.5-cm incision with a No. 15 scalpel blade through the skin and vaginal tunic on the ventral surface of both sides of the scrotum (Fig. 21-2). Remove the testis from the tunic and carefully tear the ligament of the testicle from the tunic with a dry gauze sponge. Pull the testis caudally to expose a section of the vas deferens and the vascular structures of the spermatic cord, then tie them in an overhand knot with a small Mayo needle holder or mosquito forceps. Alternatively, ligate the duct and vasculature with 2-0 to 3-0 synthetic absorbable suture. Cut the duct and vessels distal to the knot or ligature and return the spermatic cord to the inguinal canal in such a way that it can be recovered if bleeding occurs. Return the tunic to the scrotum and repeat the process for the remaining testis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree