Chapter 5 Social behavior

Chapter contents

Social organization

Social interactions between horses have been the focus of several recent studies. This is good news for domestic horses because by understanding the relationships between horses, humans can learn to build a better understanding with their equine companions. That said, there are limitations on the extent to which horses use elements of their social repertoire to communicate with humans.1 Fundamentally, we do well to remind ourselves of this, especially when riding since, clearly, horses never mount one another to take a ride.

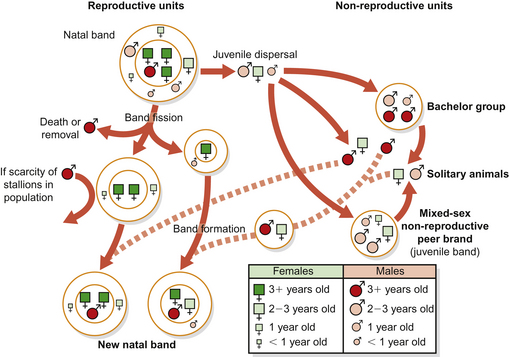

As the nature of social hierarchies in free-ranging horses, the effects of domestication and the significance of behavioral and social needs are better understood, our ability to comment on equine welfare issues is necessarily enhanced. For example, studies of groups of free-ranging horses have provided information on the roles of stallions, mares and juveniles within their natal groups (Fig. 5.1). This may provide the rationale for single-sex grouping of horses in some domestic contexts, especially where social flux is constant and agonistic interactions must be modulated for the sake of horse safety. Thoughtful planning of social groups can help to ensure normal social development, reduce some of the undesirable effects of pair-bonding on ridden work and minimize injuries from conspecifics in the paddock. It is usually better to find the optimal social milieu for horses than take the ‘safe’ option of isolation in a paddock or, worse still, a stable.2

Domestic horses are not the only beneficiaries of studies of free-ranging equids, since the humane control of feral horses is also facilitated with this sort of information. For example, given the importance of a stable social group, the relocation and confinement of feral horses, while sounding reasonably simple, is likely to modify current social structure and range use, ultimately leading to fights and injuries in the short term and the need for more intensive management in the longer term.3

Groups of horses

Other than occasional solitary individuals (which are more often than not transiently drifting between groups), two main groupings of horses occur within herds: the natal band (or birth band or family group) and the bachelor group (Fig. 5.2).4 Traditionally, horse herds are thought of as harems, comprising one stallion, his mares and foals and juveniles. This simplistic view fails to embrace the leadership role of mares and the context-specificity of the stallion’s place in the social order.

In a group of horses, the lead animal shows the way to resources, such as water, saltlicks and rolling sites, as well as initiating activities such as grazing or resting. This individual is often an older experienced mare but, depending on the context, the stallion may also direct its herd by herding and snaking, for example when he detects predators or competitors. Increasingly, the importance of mares as the functional core of the group is being recognized, with 25% of them staying permanently in their original natal band4 and with matrilineal dynasties spanning generations. Mares and their filly foals often share strong bonds and this affiliation may facilitate vertical transmission of information about optimal use of a home range. Those mares that disperse into a fresh band often remain within it for life. It is important to note that the stallion may not always be the highest ranking member of the natal band.5–7 Similarly, sex has been demonstrated to be a poor predictor of rank in foals.8

Bands with more than one stallion are not uncommon. Subject to the above, stallions within these groups establish a dominance hierarchy that helps to define roles. If there are several stallions associated with the family band, the dominant stallion copulates more than subordinate stallions.4 Band cohesion is a task shared by stallions in multi-stallion bands but the subordinate males tend to herd and occasionally mate with the lower-ranking females. One study noted that mares are more likely to leave single-stallion harems and that therefore harems with several stallions are generally more stable.9

Linklater10 defines a natal band as a stable association of mares, their pre-dispersal offspring and one or more stallions who defend and maintain the mare group, and their mating opportunities, from other males year round. For example, in New Zealand’s Kaimanawa ranges, the horse population has a social structure like that of other feral horse populations, with an even adult sex ratio, year-round breeding groups (bands) with stable adult membership consisting of 1–11 mares, 1–4 stallions, and their predispersal offspring, and bachelor groups with unstable membership.3 Changes in the adult composition of natal bands are rare (e.g. Miller11 suggests 0.75 adult changes per year). However, harems may split into smaller groups based on social attachment, when fodder becomes scarce.12

Found in all free-ranging horse populations, the bachelor group comprises males that have dispersed from natal bands. Although most colts leave the natal band at around the birth of a sibling, or when there is a shortage of playmates or food, some remain.13 However, as they mature and begin to represent a threat to a resident stallion’s mating rights, pubescent males may occasionally be ostracized from their natal band. More generally, colts gravitate to bachelor groups because that is where they find many potential play partners. Bachelor groups also provide sanctuary to older stallions, including some that have been unsuccessful in defending their bands from other stallions.14 Bachelors live in their groups adjacent to natal bands, waiting for opportunities to capture dispersing mares, perform sneak matings, herd away mares and to challenge natal band leaders. For this reason, membership of the bachelor band is subject to the greatest flux during the breeding season. Despite the companionship it offers, bachelor groups are literally full of competitors that engage in agonistic encounters that may persist over several months and may end in dispersal.15 It is therefore perhaps predictable that young stallions usually spend some time alone before forming their own harems.13 The bachelor group provides valuable physical and social learning opportunities for its transient members. In juveniles there is a relationship between time spent in the bachelor group and latency to form a harem.13

Role of stallions in natal band cohesion

The main roles of a resident stallion involve monitoring and maintaining the integrity of his band and protecting it from predators and other stallions that may attempt to steal or perform sneak matings with mares and fillies. The reproductive success of a harem stallion is limited not least by his ability to prevent such matings.16 Harem stability is not affected by the size of the harem nor by the age of the stallion, but is thought to be enhanced by the presence of subordinate stallions attached to the harem.9 Depending on the terrain, the stallion will protect his band by patrolling a radius of 10–15 m around the group as they move through the home range.6 For this reason natal band stallions are less likely than mares, juveniles or bachelors to form pair bonds. The relationships they form tend to be heterosexual (usually with all adult females in the natal band) or paternal.17

Being less timid than mares and fillies,18 stallions and colts usually take the initiative when the band encounters a potential threat. That said, the stallion’s response to a challenge depends on whether the cause of the threat is a predator or another stallion. If a predator threatens, the stallion will herd his group together and lead or drive them away from the threat using snaking gestures (Fig. 5.3). Feist19 noted that in 77% of band movements, the stallion was either driving or leading the group. Stallions sometimes herd wandering foals back to the band and protect them from danger.20

Figure 5.3 Snaking behavior used by a stallion to move other horses, especially members of his natal band.

By placing himself between the band and a predator the stallion can reduce the fragmenting effects such stimuli can have on the group. The role of the stallion in responding to potential predators is illustrated by the report that Camargue foals born into bands in which two stallions have an alliance are 20% more likely to survive than those in single-stallion bands because of reduced predation.21

If the threat is from another stallion, the initial response by the band’s stallion will be to attempt to chase the challenger away. Agonistic behaviors are discussed later, but the resident stallion’s motivation to fight depends on a number of variables summarized in a notional equation that forms the central tenet of game theory (Fig. 5.4).22 Whenever two horses dispute access to any resource, both must weigh up the value of the resource, the cost of defending it and their ability to retain it (also known as their resource-holding potential). Without performing any calculations as such, the would-be protagonists (a and b) compare

where: V is the value of the resource to that individual; RHP is the resource-holding potential of that individual; C is the cost of a fight to that individual. Factors on which these variables depend are given in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Game theory variables predicting conflict between horses, and factors on which the variables depend

| Variable | Factors include |

|---|---|

| Value | Experience of the resource, investment in the resource, short-term and long-term future needs |

| Resource-holding potential | Size, physical fitness (as evidenced by display used when the challenge is detected), ability to deceive observers, fighting experience and number of individuals involved in the dispute |

| Cost | Risks of being injured (with consequent risk of infection at the site), killed or displaced from natal band |

Snaking and herding are most likely to be seen in domestic contexts when the stallion is introduced to a group or when an existing family group is moved to a new pasture.23 After either of these interventions the stallion’s response generally returns to baseline levels by the third day.23 The addition of new mares to an established natal band does not induce herding of the original mares. However, primarily because they are chased by the stallion for up to 3 days, the introduced mares are kept at a distance (of approximately 8–12 mare lengths) from the original mares.23 Band integrity is further enhanced by a harem stallion when he facilitates bonding between mares and their neonatal foals by keeping other conspecifics away from them. Again, snaking and herding may be used for this purpose.

Despite the benefits of having the company of a stallion, band members lose some of their freedom. In the absence of a stallion, mares mutually groom more, form more stable pair bonds and have a better-developed social order.24

Role of mares in natal band cohesion

The chances of inbreeding between stallions and their daughters is reduced by the experience of having lived together before the filly’s maturity, a factor thought to prompt migration of fillies from their natal band.25 While 75% of the fillies disperse to other bands, the females that remain are the most fixed and stable members of most natal bands, often taking leadership roles in governing the band’s daily activities. Although regarded as the resident core of the equine family group, mares will disperse from natal bands notably when resources are scarce: e.g. up to 30% of adult females have been observed changing harems during the winter.9

Affiliative behavior between females is important because mares of an established band remain together even in the absence of a stallion.26 We should never underestimate the strength of social bonds among mares. Indeed there are anecdotal reports of mares abandoning their own foals to reach the comfort of their herd mates. These affiliations may have their origins in foal associations since fillies tend to spend more time with other fillies than with colts.27 Daughters also tend to remain closely associated with their dams.17,28

As discussed in detail later in this chapter, the concept of hierarchy is controversial since some commentators fear that it legitimizes human domination of and violence toward horses. However, as we use clearer terminology that provides the most parsimonious explanation of effective and safe human–horse and horse–human interactions and thus advances the welfare of horses, we must not deny the importance of social order, since it is highly adaptive in reducing intraspecific aggression. The rank of a mare has a predictive effect on her role in band cohesion. For example, as a reflection of the investment they have made in the group, dominant mares are more likely to defend the area around the group. Although territorial behavior is an irregular feature of the equine ethogram,29 in some free-ranging populations, such as those in Shackleford Banks on the eastern coast of the USA, which show defense of a territory rather than simply maintenance of the integrity of the band,30 higher-ranking mares within the natal band are more often involved in mutual grooming with the resident stallion, while lower-ranking mares are the chief recipients of his snaking and herding attention when he rounds up the band. Most adult mares in a natal band will contribute to band cohesion by responding to the sound of the resident stallion’s call.31

Role of juveniles in natal band cohesion

In a natal band, the juveniles issue the least amount of aggressive behavior and conduct the most non-agonistic behavior.7 One of the main behaviors of foals is play: it is very important that they learn how to interact with one another and to establish pair bonds (see Ch. 10). Play in foals is unrelated to rank. So, the play-rank order of foals, as measured by the number of times a foal left a bout of play, is not significantly correlated with social rank order determined by agonistic interactions.32 Yearlings and two- and three-year-olds continue to be involved in play activity but are also seen nipping and wrestling each other as they consolidate their social order and as they practice herding or fighting for adulthood.

Group size and home ranges

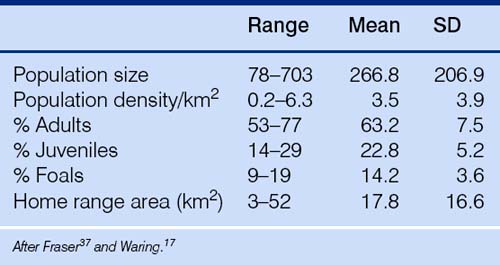

Herds of horses may be as large as 600 (Machteld van Dierendonck, personal communication 2002). Bands within herds form relatively stable nuclei33–35 that are often at their most discrete when resting but may graze in close proximity to one another and usually unite when fleeing from a predatory threat. Band size tends to vary with population density. For example it can range from 12.3 in Shackleford Banks,30 with a population density of 11 individuals/km2 to 3.3 in Wassuk Ridge, in the Nevada Desert, with a population density of 0.1.36 Because of the terrain and its resources, horse density in a given ecological sector can vary: e.g. while the population density in the Auahitotara of New Zealand averaged 3.6 horses/km2, it ranged from 0.9–5.2 horses/km2 within different zones.3 Group size therefore is dependent on the density and pattern of distribution of resources, and this is why, when external resources are provided, groups can become larger than those observed in the free-ranging state. For example, in working ponies that are seasonally managed on a free-living basis, groups of 30 or more can exist.37 Island populations, such as those on Sable Islands and Shackleford Banks, have higher population densities than those with fewer limitations on their ability to spread.30,38 Demographic data on feral horse groups in North America are given in Table 5.2.

Home ranges incorporate grazing sites, waterholes, rolling sites, shade, windbreaks and refuges from insects and can vary in area from 0.9–52 km2.39 Exploitation of the home range depends on numerous variables including the climate, the season, predation risk and the prevalence of biting insects. For example, Auahitotara horses generally avoid high altitudes, southern aspects, steeper slopes, bare ground and forest remnants.3 Instead they tend to occupy north-facing slopes (because they have warmer aspects) with short vegetation and zones with well-nourished swards. In spring and summer when subsistence is less of a challenge and there is less need to forage in hostile terrain, they tend to be found on gentler slopes.3

Horse populations do not use all parts of their home range equally since the grazing is rarely of uniform value and the emergence of latrine areas is normal (see Chs 8 and 9). Thus bands tend to spend much of their time in relatively small focal areas within the home range.17 Natal bands often shift with the season such that in spring they gravitate to river basin and stream valley floors for the beginning of foaling and mating and, when there is a chance of frost, to higher altitudes in autumn and winter.3 The appeal of certain areas changes with the season. For example, whereas during the winter months they may avoid standing in water, during the summer months horses may be driven into surf or shallow bays by biting insects. Equally, the cooling effect of rolling and standing in water should not be underestimated. That said, in some groups of horses no pattern of cyclical use of areas has emerged.17 Since the use of terrain seems to be initiated by leading members of the group and since a change of leader may bring a change in a band’s use of resources, this finding may have arisen because behavioral observations were coincidentally made at a time of flux in the band’s composition or social order.

Social behavior in feral horse populations is more common than territorial behavior, in that if one band of horses encounters another, any defensiveness shown usually appears to be an attempt to maintain the integrity of the band rather than to defend a site.17 Although the home range of one natal band often overlaps entirely with the home ranges of others, natal bands and bachelor groups are loyal to undefended home ranges with central core use areas.3

In cases where home ranges overlap, a social order among groups can be observed that allows the predictable displacement of subordinate (usually smaller) bands and individuals from shared resources such as watering-holes. Although linked to the size of the group, its relative rank compared with others is not a function of the number of males it contains.34 This is illustrated by the deference exhibited by bachelor groups to natal bands and by the way in which the rank of a bachelor is enhanced once he has acquired a mare.34 Disputes between bands are generally resolved by interaction between one or occasionally two high-ranking representatives from each. The remainder of both bands typically look on and await the outcome before accessing resources in an order determined by their representatives.34

Social order

The establishment of defined social status within any group of equids promotes stability within the band. A stable social order within the band decreases the accumulative amount of injury by allowing threats of kicks and, perhaps more importantly, bites to replace the aggressive responses themselves.7

Each horse’s position within the band is held through a blend of aggression and appeasement behavior. Aggressive behavior can be biting, kicking, circling and displacement, but the most common response to a competitor is a threat to kick or bite. Rank is determined not only by threats issued but also deference to threats received. Such submission may involve lowering the head and averting the gaze. Unfortunately, the intraspecific harmony seen in stable horse groups (facilitated largely by deference) is sometimes hijacked by humans seeking to justify the use of force to render horses submissive.1

Houpt et al40 found that although individual rank order is unidirectional it may not be linear throughout the group. Thus A may dominate B who may dominate C, but C may dominate A.40 This facilitates the formation of so-called social triangles. While rank orders are generally linear in the top and bottom of a band’s organization, most triangles occur in the middle.41

If a social order were not developed and maintained, each horse would need to affirm its rank by increasing levels of aggression during every dispute with a conspecific over a resource. Without a hierarchy, injury and distress associated with social flux may have reproductive costs, e.g. the rate of conception might be decreased and there could be an increase in the rate of fetal and foal mortality.42 In general, a social structure is important for organization, especially during times of emergency such as when a predator approaches (Fig. 5.5). A defined social structure based on affiliative relationships allows the band to mount an appropriate response, be it fight or flight, as the lead animal rises to the defense of the group or herds it together to escape. Social order per se is highly adaptive. However, the concept of hierarchy unsettles some applied ethologists because, being resource-dependent, it is complex and therefore the outcomes of agonistic interactions between two or more individuals are sometimes difficult to predict but also because it has been used to justify fear-eliciting activities within the human–horse dyad.

Figure 5.5 A mare moves forward to defend her group by attacking an approaching dog.

(Photographs courtesy of Michael Jervis-Chaston.)

The empirical determination of rank is complex and not easily predicted. Height or weight or both have been found to correlate with rank in many studies43–45 but not all.5,41 Age more usually shows a correlation with rank in studies of feral E. caballus6,43,46 and E. przewalski47 but again this is not always the case.42 It is appropriate that age should contribute to social status since it is likely to reflect experience in dealing with local challenges and a wealth of knowledge about how best to exploit the resources in the home range.7 That said, in their dotage the oldest mares may relinquish leadership but occupy a beta position, much more elevated than their body condition would suggest. Perhaps this reflects some sort of respect earned earlier in life (Machteld van Dierendonck, personal communication 2002). In managed herds, the length of residency within a band also contributes to the determination of rank.41,48 In geldings, rank seems strongly influenced by an individual’s position in the social hierarchy at the time of castration (see Ch. 11).

Either sex can out-rank the other because there is little sexual dimorphism in the sizes of hooves and teeth, which are a horse’s main weapons.6 Stallions’ ranks are very much context-dependent. They may rarely dominate, as they have less contact with the band than female peers because of their need to patrol around rather than within the band. Furthermore they do not participate in many aggressive encounters if they enter the band chiefly during sexual situations.6 Therefore when a youthful stallion secures mating rights in a band containing mares older than himself, the oldest yet healthiest mare will tend to prevail in a leadership role. Although over 80% of threats are directed down the dominance hierarchy,32 the use of the term ‘dominance’ is somewhat controversial since some authors highlight avoidance behavior on the part of subordinates as being the main activity necessary to maintain the order. In view of this, it has been argued37 that avoidance order is a better measure of the social system than the ‘aggression order’.

In the process of learning to recognize their place in the hierarchy, yearlings receive the largest number of attacks (46% according to Keiper & Receveur7). Significant positive correlations have been found between rank of mares and foals and the rate at which they directed aggression to other herd members.8

As suckling foals play away from their dams, they establish a hierarchy based largely on birth order such that there is a linear relationship between age and social position.7,8 Although weaning tends to have a disruptive effect on the ranks of foals (so that birth order no longer correlates with rank), significant correlations have been found between mare rank and the rank of foals both before and after weaning.8,32 This would suggest that the influence of the dam is relatively constant over time.8

Since the adult offspring of a high-ranking mother does not necessarily become high-ranking, it cannot be said that resource-holding potential is purely genetic.6 Status is a learned relationship between two individuals, and learning plays a role in the development of effective displacing strategies, which can include deceptive responses such as bluffing. Additionally there may be heritable behavioral predispositions in the high-ranking dynasties within a herd. Although offspring may learn aggressive behavior from their mothers this is challenged in part by evidence of inverse correlations between aggression rates and rank in foals.32 Perhaps they have only to learn how to impose their rank rather than doing so frequently. One alternative is that status is bestowed upon the foals of high-ranking mares simply by association with their dams, since mares may assist their foals in agonistic encounters with other foals.8 It is acknowledged that foals share their mother’s rank while she is in close proximity17 but that they are more likely to show displays thought to be deferential such as snapping (tooth-clapping, yawing, champing, yamming; Fig. 5.6) to adults when beyond her protection.43 Furthermore the rates of aggression towards foals rise with weaning as the mare’s support is withdrawn.8 The relative contribution of environmental and genetic factors will be better understood when the influence of non-biological mothers can be measured from studies of foals that have been transferred as embryos or cross-fostered after birth.

Figure 5.6 Youngster showing snapping response to an older horse.

(Photograph courtesy of Francis Burton.)

Although mares may undergo significant changes in social behavior at the time of foaling,49 no coincident changes in social status have been reported with foaling,43 so mares with foals at foot do not necessarily rank higher than a mare without a foal.

The effect of rank on behavior

By definition, with higher rank comes priority access to most resources. In every dispute the rank of protagonists correlates with their resource-holding potential and contributes to the prediction of the outcome. However, rank alone is not a simple, absolute predictor, since game theory applies, too. Therefore the outcome must also remain a function of the value of the resource (i.e. the motivation to acquire the resource) and the cost of any fight to possess it. For these reasons rank is also context-dependent, especially in stallions.

Rank has been correlated with the priority bestowed on those horses that gain first access to maintenance resources such as resting sites and watering holes,34 unless they have been distracted by having to repel another band. Conversely, rank dictates the order in which bachelors eliminate on one another’s excrement,24 and all bands use rolling sites50 (Fig. 5.7). Rank influences social dynamics within a band, including the selection of nearest neighbors and mutual grooming partners.46

The rank of an individual horse does not influence its sociability rate in any group.8 However, the debate continues about the role of the higher-ranking partner in mutual grooming pairs, with evidence that high status animals may be both more likely46 and less likely43 to start a bout when grooming started asynchronously.

Despite the relationship between age and rank, difference in the ages of band members influences social networks. Bonded pairs with less difference in age that demonstrate frequent grooming, usually remain in close proximity to one another, beyond the effects of rank and kinship.51 Additionally, middle-ranking horses tend to be more frequently in the close vicinity of another horse than high-ranking or low-ranking horses.41 Again, the mid-ranks are also characterized by social triangles.41

There are a number of ways in which social rank affects reproductive behavior. Just as stallions can reject maiden mares, they have been reported to select high-ranking estrous mares for mating when offered a choice.52 Males outside the natal band and low-ranking (juvenile) males within it are seldom able to mate with mature mares unless by sneak matings, because the resident stallion consorts with these mares when they are in estrus. The peripheral and subordinate stallions can therefore usually mate only with lower-ranking mares with reduced biological fitness. The trade-off for these males is that they have not invested time in protecting these females. For mares, elevated rank means they are less likely to be harassed by these males seeking sneak matings. As they solicit the attentions of the senior stallion they may also be seen chasing away subordinate females that would otherwise divert his attention.50

The benefits of high rank in terms of biological fitness are clear. For example, since the foals of high-ranking mares may grow bigger and faster than other foals in the natal band, they may breed earlier and the colts among them may be more likely to gain a harem.8,53 Other, less favorable associations with high rank are becoming better understood, with studies in wild dogs indicating that rank is positively correlated with cortisol concentrations.54 In horses, one might predict this to be the case in herd leaders because of the associated burden of having to maintain band integrity and investigate potentially dangerous stimuli. Similarly, recent data demonstrate that the foals of higher-ranking mares are more likely to develop oral stereotypies than foals of middle- or low-ranking dams.55 It is speculated that this may reflect the influence of mares’ behavior towards foals prior to weaning or may relate to the nature of the mare–foal bond and effects of severance at weaning. Low-ranking mares and those in poor condition are more likely to have female foals, which are better able to reproduce than colts from dams on marginal nutrition.56

Measuring rank

The factors that influence rank are complex, as is determining rank within a group of horses. The absence of an established protocol for measuring social hierarchies in horses accounts for the lack of consensus among studies. Perhaps because there are fewer complexities such as social triangles and because of the complete absence of mare–foal dyads, measuring rank is easier in all-male groups than in natal bands.24 The importance of deference displays by subordinate horses when withdrawing from disputes over resources is now being recognized, so instead of establishing hierarchy solely on the basis of threats given,7 the trend is towards including submissive gestures32,45 and calculating rank only from submission data.8

It is generally true that one can best see the dominance relations between individuals at the site of limited resources: water holes, saltlicks, sandy places to roll, shelter, etc. It is natural for horses to attempt to displace each other as they compete for affiliates, mates, food, salt or water. For this reason, some studies of hierarchy tend to record all occurrences of agonistic behavior between pairs of subjects during feeding of supplemental grain.8 However, the desire to acquire or defend food pellets in competitive situations is not necessarily the same for all individuals involved. Additionally, rank in an isolated dyad is not necessarily a true reflection of what applies in an unmanipulated group that may feature coalitions, social triangles, leadership and defense.

Because simply recording the outcome of a bout is an inelegant measure of rank, submissive and aggressive behaviors should be analyzed in detail. This approach has shown that agonistic responses involving the head are related to offensive behaviors, while the hindquarters are used both offensively and defensively.41 So, when scoring a dispute between two horses to determine rank, it is advisable to summate bites and bite threats separately from kicks and threats to kick because the latter may be less useful for determining hierarchy.41

Affiliations

Under free-range conditions, even where the territory is extensive, group bonding is important to the extent that horses maintain continual visual and, to some extent olfactory, contact with each other.37 A central mechanism of band cohesion is the establishment of affiliations, notably pair bonds and mare–foal bonds.57 Pair bonds in bachelor groups are generally weaker than those observed in natal bands and become more tenuous as bachelors mature and are driven to establish reproductive relationships.17

While domestic horses generally group together according to certain sex or sex–age classes – adult mares, adult geldings, foals, juveniles – mares sometimes socialize according to their reproductive state: pregnant, postpartum and barren (Machteld van Dierendock, personal communication 2002). Most horses have one or more preferred associates with whom they maintain closer proximity than with other herd members.46 The resilient bonds between such paired affiliates are of particular importance among equids and are demonstrated by reciprocal following, mutual grooming and standing together (Table 5.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree