Chapter 6 Communication

Chapter contents

Body language

Monitoring of Przewalski horses has shown that a band’s behavior can be synchronized between 50% and 98% of the time.1 Communication between members of a social group of horses facilitates this synchrony. Horses most often communicate without using their voices. This is because they are social prey animals that must organize themselves as a group but without attracting predators. Used to scan for responses after vocalization, the ears are the most important body part in equine non-vocal communication. When flattened, they generally qualify all concurrent interactions as agonistic, and the extent to which they are pinned back correlates with the gravity of a threat.2 An important feature of bite threats, ear pinning may have evolved simply as a means of avoiding ear injury during fighting, but it has taken on an additional signaling function. Rather than being pinned back, ears are simply turned to point backwards during avoidance responses as horses retreat as a display of submission.3

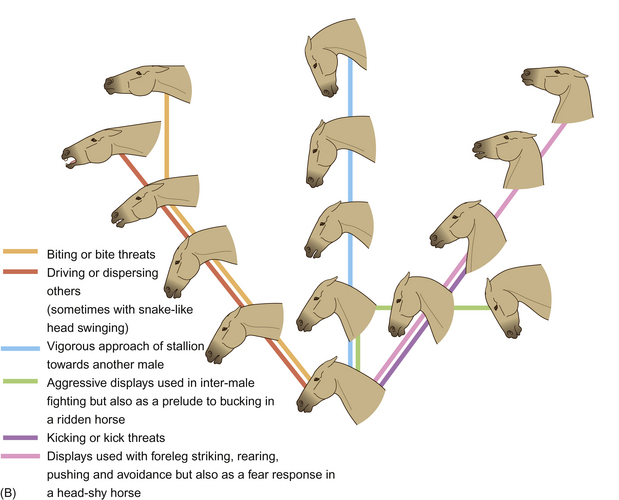

Ears are not central to expressions of threatened aggression alone. Indeed they are focal to a series of expressions elegantly described by Waring & Dark.4 Neck posture changes significantly during agonistic encounters between horses, being flexed during approach responses and often arched in response to threats, especially by stallions.3 It is important to note that such arching is extremely transient and therefore cannot plausibly be cited as a natural analogue of the prolonged hyperflexion seen in Rollkur or so-called long-deep-and-round training.5 Head bowing that involves rhythmic exaggerated flexing of the neck to the extent that the muzzle may touch the pectoral region is seen as a synchronous display by two stallions as they approach one another head to head.3

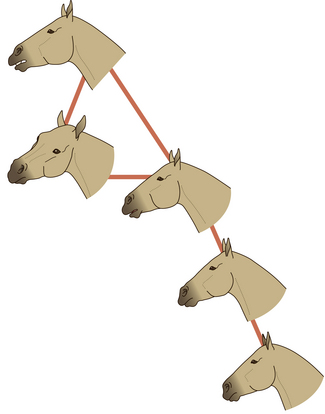

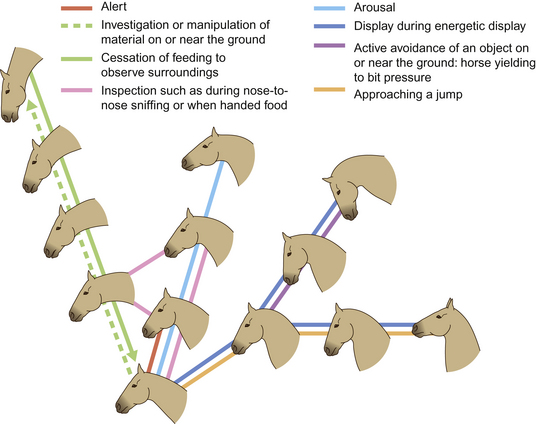

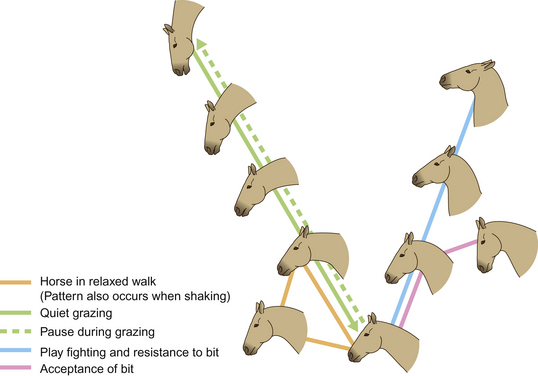

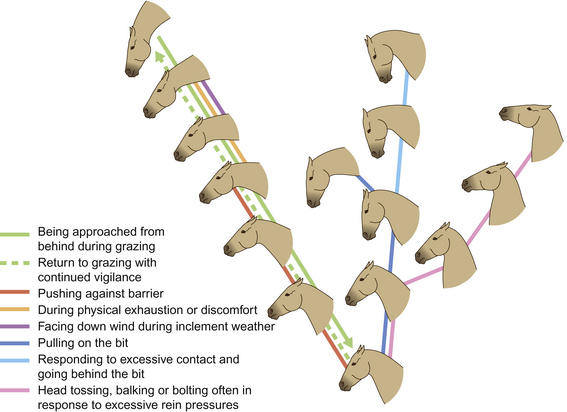

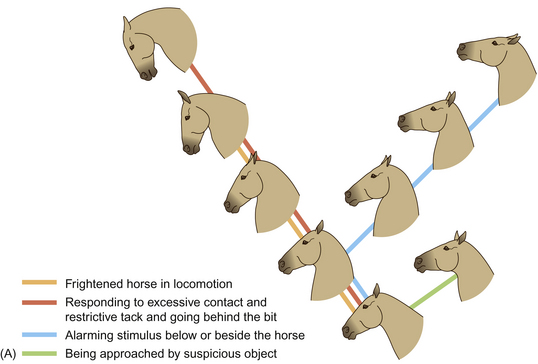

The series of illustrations in this chapter demonstrates the importance in communication of various features of the equine head, including the nostrils or nares. The nares dilate and constrict with changes in mood. For example, during forward attention, as a horse sniffs the ground, they are moderately dilated whereas during aggression they become drawn back to form wrinkles on their aboral edge. In combination with head position, the ears and nares contribute to expressions of forward attention (Fig. 6.1), lateral attention (Fig. 6.2), backward attention, alarm, aggression, submission and pleasure.

Figure 6.1 Expressions of forward attention.

(Redrawn from Waring2, after Waring & Dark4, with permission.)

Figure 6.2 Expressions of lateral attention.

(Redrawn from Waring2, after Waring & Dark4, with permission.)

When ears are pointing forward the horse is, as one might expect, attending to a stimulus in front of it. Horses are sometimes seen pointing their ears in two directions (see, for example, Fig. 2.14 on p. 48). Swiveling of the ears is associated with pain; e.g. a horse with colic may swivel its ears back in the direction of its abdomen before it gets to the stage of kicking at its belly.

The positions of horses’ ears in a moving band seems to be predicated on the spatial positions of those horses in the group. Horses at the front of a moving group tend to have their ears forward while those to the rear orient their ears backwards. This suggests that, in this instance, ears are used chiefly for surveillance rather than for signaling. To that extent, horses that are not leading may have the rear under surveillance (Fig. 6.3). This strategy makes sense for the safety of the group since it allows the leaders to concentrate on hazards ahead of the group. Some racehorse trainers use blinkers to reduce the influence of other horses (Fig. 6.4).

Figure 6.3 Expressions of backward attention.

(Redrawn from Waring2, after Waring & Dark4, with permission.)

Figure 6.4 A racehorse wearing blinkers to modify its flight response and reduce distraction from other horses.

(Photo courtesy of Sandra Jorgensen.)

When horses are frightened by or simply suspicious of a stimulus, their alarm is often indicated by switching the direction of the ears and by a tense mouth and dilated nostrils. Alarmed horses tend to withdraw from such stimuli with rather jerky movements that alert conspecifics and contribute as a survival strategy because they confound a predator’s ability to predict the horse’s intended route of escape. The same unpredictable responses can make frightened horses dangerous to lead and ride and thus alarm conspecific companions (see Ch. 15).

Aggressive horses look similar to alarmed horses (Fig. 6.5). Indeed, one expression can give rise to the other, except that aggressive horses tend to pin their ears back and wrinkle the aboral edge of their nares, sometimes to the extent that their teeth are exposed. When driving his mares (see Ch. 11), a stallion feigns snapping2 and drops his head below the horizontal with additional nodding and swinging movements. These embellishments to the posturing of regular aggression represent expressive movements that qualify the signal as a driving cue rather than direct aggression.

Figure 6.5 Expressions of (A) alarm and (B) aggression.

(Redrawn from Waring2, after Waring & Dark4, with permission.)

The reasons for horses to signal submission have been dealt with in the previous chapter but it is worth emphasizing that, in the midst of a conflict between horses, it is often the appeasement signals that determine the outcome. These may be very subtle. Mindful of the example offered by Clever Hans (see Ch. 4), we would do well to remember that, with their excellent vision, horses are able to detect minute cues in animals around them. When submitting, a horse will look away from the threat and try to shuffle away, often with its croup and tail lowered. If trapped in a melée, submissive horses raise their heads and often show the whites of their eyes.

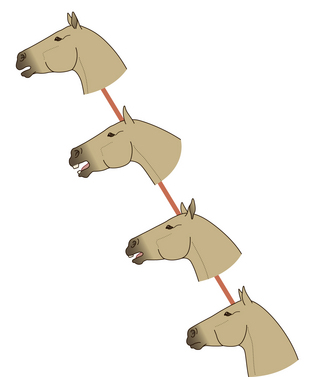

Although still the source of some controversy, the snapping action of youngsters is regarded as an attempt to communicate (Fig. 6.6). The extent to which it is successful remains unclear. Since prevalence is inversely correlated with the age of the performer, it may be that its relevance wanes as its refinement peaks. It is not offered exclusively to horses, having been observed being offered to cows, humans and horse-rider pairs. Although sometimes accompanied by sucking and tongue clicking sounds, it is chiefly a visual signal that is marked by the assumption of a characteristically extended neck, head lowering and exposure of the teeth.2 The performer often lolls its ears laterally but maintains visual focus on its target.

Figure 6.6 Juvenile greeting used on adults.

(Redrawn from Waring2, after Waring & Dark4, with permission.)

While the lips are usually drawn back to expose the incisors during snapping displays, they are often pursed as part of a head threat display.3 The teeth and masseter muscles may be clenched during pain even though the lips may appear loose. The same loose-lipped appearance has been noted in some sexually receptive mares and many older animals.

During mutual grooming, horses often extend the upper lip (Fig. 6.7) and move it from side to side and sometimes tilt their head and swivel their eyes laterally. With the panoramic quality of equine vision, it is possible that a grooming partner is able to detect this response as a signal that it has located a seat of irritation. This response, also seen when a solitary horse uses a scratching post, is sometimes accompanied by deep respiratory excursions and some luxuriant groaning.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree