Chapter 7 Skin Diseases

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Papillomatosis (Fibropapillomas, “Warts”)

Etiology

Papillomas are the most common tumors in dairy cattle; fortunately most papillomas are benign and self-limiting. Animals between 6 and 24 months seem most at risk for warts, and previous incidence of the tumors gives an individual a degree of immunity. Papillomas are well documented to be caused by bovine papilloma virus (BPV) types 1 through 6. These viruses have some common antigenic components but do not have good immunologic cross-reactivity. BPV1 and especially BPV2 cause typical warts on the head, neck, trunk, and legs of young cattle (Figure 7-1). A “typical” wart means that a true fibropapilloma exists histopathologically. These masses usually are cauliflower-like, rough, or crusty-surfaced skin lesions that are colored white to gray. Some appear flatter, gray, and have a broad-based skin attachment. Others have a pedunculated base. The virus infects the basal cells of the epithelium, and as these cells eventually reach the surface, large quantities of virus are available to contaminate fomites and the environment. Therefore warts tend to become endemic rather than occur sporadically. Stanchions, feed bunks, neck straps, brushes, halters, pens, and back rubs all become coated with virus. Abrasion of the skin caused by mild trauma from sharp objects (e.g., nails, splintered wood, barbed wire, and bolt ends) allows inoculation of the virus into skin and will increase the incidence in a group of calves. Epidemic and endemic situations also have been associated with dehorning (Figure 7-2), ear tagging, and the use of tattooing devices or emasculatomes when disinfection of a common instrument has not been performed. This is especially true when laypeople perform the aforementioned procedures. Insects also have been suspected of spreading or inoculating the virus into skin, but this remains difficult to prove.

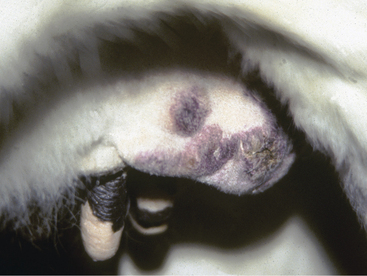

Cattle with large multiple warts that do not regress probably have concurrent deficient cell-mediated immunity (Figure 7-3) or some other immunodeficiency such as persistent infection with bovine virus diarrhea virus (BVDV) or bovine leukocyte adhesion deficiency (BLAD). Genital fibropapillomas caused by BPV1 are commonly found on the penis of young bulls, on the teats, and occasionally in the vagina of heifers.

BPV4, as well as BPV1 and BPV2, may contribute to urinary bladder tumors in cattle consuming bracken fern at pasture. This condition, known as enzootic hematuria, can be life threatening to affected cattle.

BPV5 causes so-called “rice-grain” teat fibropapillomas, probably the most common form of teat wart seen in dairy cattle in the United States. (This virus is discussed further in Chapter 8). It is spread by milking procedures and machines that predispose to teat chapping or minor teat abrasions. Similarly BPV6 has been shown to cause papillomatous frondlike lesions on the skin of the udder.

Diagnosis

Clinical signs are sufficient for diagnosis in most instances. Atypical lesions may require biopsy and histopathologic study. Gross sectioning of surgically excised fibropapillomas also is suggestive because epidermal proliferation over dermal fibroplasia is obvious on cut sections.

Dermatophytosis (“Ringworm”)

Etiology

Dermatophytes affect the keratinized layers of skin thanks to toxins and allergens with resultant exudation, crusting, and alopecia. Fungal organisms themselves do not invade tissue and survive best when they provoke little host inflammatory reaction. Lesions tend to be oval or circular and are often multifocal. Incubation requires 1 to 4 weeks, and lesions persist for 1 to 3 months in most circumstances. Infection by contact is accelerated by mechanical irritation of the skin by contaminated objects. Stanchions, neck straps, halters, milking straps for old-fashioned bucket milking machines, brushes or curry combs, chutes, and other devices may spread infection through a group of cattle. Chronically ill, unthrifty, poorly nourished, or acutely ill cattle will show diffuse or rapidly progressive lesions compared with herdmates. This may imply either cellular or humoral factors that contribute toward worsening of dermatophytosis. Calves persistently infected with BVDV and calves with BLAD are examples of animals that frequently have severe ringworm lesions, whereas healthy herdmates remain either unaffected or have only mild lesions. Adult cows or heifers with typical ringworm lesions may progress to diffuse lesions when stressed by acute severe infections such as pneumonia or peritonitis. Exogenous corticosteroids will worsen existing ringworm lesions.

Signs

Round or oval areas of crusting and alopecia that range from 1.0 to 5.0 cm in diameter are typical for ringworm in calves. Early lesions may appear raised because of serum oozing or secondary bacterial pyoderma underlying the crust (Figure 7-4). In calves, the periocular region, ears, muzzle, neck, and trunk are most usually affected, but lesions may occur anywhere (Figures 7-5 and 7-6). Head and neck lesions are common because lock-ins, stanchions, or neck straps become contaminated and help spread the disease. Posts or beams that are used for scratching may provide an area that infects the trunk in a group of heifers. The escutcheon is another area that frequently is affected with one or more lesions. Skin lesions may be painful but are rarely pruritic.

Figure 7-4 Raised, crusted lesions of ringworm involving the facial and periocular region of a Holstein calf.

During ringworm outbreaks in adult cattle, individual cows that experience unassociated systemic illness may show dramatic worsening of their ringworm lesions. Ketotic cattle treated with corticosteroids also will show worsening of the ringworm condition. Adult cattle also may have lesions on the udder, skin of the flank, or hind limbs that increase the risk of zoonotic disease because these lesions occur where milkers come into contact with the animals. Lesions of ringworm in milkers or handlers of infected cattle are a common occurrence. Ringworm is the most common example of a zoonosis in cattle practice.

Treatment

Topical treatments that probably are efficacious are:

Numbers 1 through 3 are applied as a spray or dip daily for 5 days, then once weekly until cured.

Systemic treatment that probably is efficacious:

Systemic treatments that may be efficacious:

Dermatophilosis (“Rain Scald”)

Etiology

D. congolensis probably is part of the normal skin flora in some cattle and is known to proliferate in a moist environment. Cattle that are highly stressed by illness, transient or long-standing alterations of their immune status, or treated with corticosteroids may develop severe lesions.

Signs

In animals housed outdoors, a crusty dermatitis along the topline represents the classical distribution of dermatophilosis. Animals with short hair coats may have a folliculitis with mild raised crusts and tufts of hair, whereas more classical cases with long hair coats have thick tufts of matted hair and crusts that can be plucked off to expose a thick, yellow-green pus on the skin and attachment areas of crust. Pink areas of dermis may be apparent after removal of crusted tufts of hair (Figure 7-7).

Cattle that have access to farm ponds, deep mud, or lush wet pastures may develop lesions on the lower limbs and muzzle rather than the classical dorsal distribution. Bulls may develop the lesions on the skin of the scrotum, and occasionally cows develop lesions on the udder and/or teats (see Chapter 8).

Dermatophilosis that becomes widespread or covers more than 50% of the body surface may be fatal. Fortunately severe dermatophilosis is rare in the United States but remains a serious cause of cattle mortality in tropical climates, where greater heat and humidity coupled with more profound insect loads exist (Figure 7-8). Death may occur in severe cases as a result of debility, discomfort, protein loss, and septicemia.

Treatment

Treatment is difficult and time consuming. In wet or damp, cold environments, the thought of bathing large numbers of cows to treat the condition is dismissed quickly by most owners. Infections often resolve spontaneously over several weeks if affected animals can be kept dry. In addition to keeping the animals dry, it is helpful to remove tufts of crusted hair or to clip matted hair to reduce the numbers of organisms present. Whenever possible, combining grooming with an iodine or chlorhexidine shampoo is an excellent treatment. Unlike ringworm, dermatophilosis lesions seldom are focal enough to be treated individually. Therefore overall grooming or clipping usually is necessary. Clippers, combs, and other grooming equipment must be thoroughly disinfected before reuse with chlorhexidine, iodophors, or bleach to prevent cross-contamination. The rational treatment of the disease also is complicated by the fact that in the winter animals may need as much hair as possible to survive outdoors. Unless there is an opportunity for indoor housing, owners are reluctant to clip hair. Systemic therapy with penicillin or oxytetracycline is highly efficacious and can be life saving for animals with diffuse disease. Therefore standard treatment recommendations include:

Grooming to remove crusts is very helpful

Clipping long hair, if possible

Other Cutaneous Diseases Caused by Infectious Agents

Numerous bacterial, fungal, viral, and protozoal infections may produce dermatologic lesions. An in-depth discussion of these diseases—especially their noncutaneous manifestations—is beyond the scope of this chapter, but a listing of these disorders is provided in Table 7-1.

TABLE 7-1 Miscellaneous Bacterial, Fungal, Viral, and Protozoal Disorders of the Skin

| Disorders | Signs |

|---|---|

| Bacterial disorders | |

| Abscess | Any age; anywhere on body; fluctuant, subcutaneous, often painful; especially Arcanobacterium pyogenes |

| Actinobacillosis (“wooden tongue”) | Adult; single or multiple nodules and abscesses; especially face, head, and neck; Actinobacillus lignieresii |

| Actinomycosis (“lumpy jaw”) | Adult; firm, variably painful, immovable swellings with nodules, abscesses, and draining tracts; especially mandible and maxilla; Actinomyces bovis and A. israelii |

| Bacterial pseudomycetoma (“botryomycosis”) | Adult; single or multiple crusted nodules and ulcers on udder; Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| Cellulitis | Adult; marked swelling and pain with variable exudation and draining tracts; especially leg (Staphylococcus aureus or A. pyogenes) or face, neck, and brisket (Fusobacterium necrophorum, Bacteroides spp., Pasteurella septica) |

| Clostridial cellulitis | Any age; acute onset and rapidly fatal; poorly circumscribed, painful, warm, pitting, deep swellings progressing to necrosis and slough with variable crepitus; especially leg (Clostridium chauvoei; “black leg”) or head, neck, shoulder, abdomen, groin, and following tail docking (C. septicum, C. sordelli, C. perfringens; “malignant edema”) |

| Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis granuloma | Adult; single or multiple subcutaneous abscesses and ulcerated nodules; anywhere on body (especially head, neck, shoulder, flank, and thigh) |

| Farcy | Adult; firm, painless subcutaneous nodules with enlarged and palpable lymphatics; anywhere on body (especially head, neck, shoulder, legs); Mycobacterium senegalense |

| Impetigo | Adult; pustules, erosions, and crusts on udder, teats, ventral abdomen, medial thighs, vulva, perineum, and ventral tail; nonpruritic and nonpainful; S. aureus |

| Necrobacillosis | Adult; moist, necrotic, ulcerative, and foul-smelling lesions anywhere on body (especially axillae, groin, udder, between digits); F. necrophorum |

| Nodular thelitis | Adult; painful papules, plaques, nodules, and ulcers on teats and udder; Mycobacterium terrae and M. gordonae |

| Opportunistic mycobacterial granuloma | Adult; single or multiple nodules, often in chains with enlarged and palpable lymphatics; especially distal leg; Mycobacterium kansasii |

| Staphylococcal folliculitis and furunculosis | Adult; tufted papules, crusts, and alopecia; anywhere on body (especially rump, tail, perineum, distal legs, neck, face); nonpruritic; S. aureus, occasionally S. hyicus |

| Ulcerative lymphangitis | Adult; firm to fluctuant nodules, often with enlarged and palpable lymphatics, usually unilateral on distal leg, shoulder, neck, or flank; especially A. pyogenes, C. pseudotuberculosis, and S. aureus |

| Fungal disorders | |

| Phaeohyphomycosis | Multiple ulcerated, oozing nodules over rump and thighs (Dreschlera rostrata) or pinnae, tail, vulva, and thighs (D. spicifera) |

| Malassezia otitis externa | Ceruminous to suppurative otitis externa; predominantly Malassezia sympodialis in summer and M. globosa in winter; organism may also cause udder dermatitis |

| Viral disorders | |

| Cowpox (orthopoxvirus) | Typical pox lesions and thick, red crusts; usually confined to teats and udder, but occasionally medial thighs, perineum, vulva, and scrotum |

| Pseudocowpox (parapox virus) | Edema, pain, orange papules, dark red crusts (especially in “ring” or “horseshoe” shape); usually teats and udder, but occasionally medial thighs, perineum, and scrotum |

| Bovine popular stomatitis (parapoxvirus) | Typical pox lesions on muzzle, nostrils, and lips, especially on calves; occasionally flanks, abdomen, hind legs, scrotum, prepuce, and teats |

| Bovine lumpy skin disease (capripox virus) | Acute onset of papules and nodules, progressing to necrosis, slough, ulcer, and scar; especially tail, head, neck, legs, perineum, udder, and scrotum |

| Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (bovine herpesvirus 1) | Erythema, pustules, necrosis, and ulceration of muzzle, vulva, and rarely perineum and scrotum |

| Herpes mammillitis (bovine herpesvirus 2) | Acute swollen, tender teats, and udder skin progressing to vesicles, sloughing, and ulceration and crusting |

| Pseudolumpy skin disease (bovine herpesvirus 3) | Similar in appearance and distribution to true lumpy skin disease but more superficial |

| Herpes mammary pustular dermatitis (bovine herpesvirus 4) | Vesicle and pustules on lateral and ventral aspects of udder |

| Malignant catarrhal fever (alcelaphine herpes virus 1, wildebeest; ovine herpesvirus 2, sheep) | Erythema, scaling, necrosis, ulceration, and crusting of muzzle and face, and occasionally udder, teats, vulva, and scrotum; variable coronitis |

| Pseudorabies (porcine herpesvirus 1) | Intense, localized, unilateral pruritus; especially head, neck, thorax, flank, and perineum |

| Bovine virus diarrhea (pestivirus) | Erosions of muzzle, lips, and nostrils, and occasionally vulva, prepuce, coronet, and interdigital space; rarely crusts, scales, and alopecia on perineum, medial thighs, and neck |

| Foot-and-mouth disease (aphthovirus) | Vesicles and bullae, painful erosions and ulcers in mouth and on muzzle, nostrils, coronet, interdigital space, udder, and teats |

| Vesicular stomatitis (vesiculovirus) | Vesicles, painful erosions and ulcers in mouth and on lips, muzzle, feet, and occasionally prepuce, udder, and teats |

| Rinderpest (morbillivirus) | Erythema, papules, oozing, crusts, and alopecia over perineum, flanks, medial thighs, neck, scrotum, udder, and teats |

| Bluetongue (orbivirus) | Edema, dryness, cracking, and peeling of muzzle and lips; ulcers and crusts may be seen on udder and teats |

| Protozoal disorders | |

| Sarcocystosis | Loss of tail switch; variable alopecia of pinnae and distal legs |

| Besnoitiosis | Warm, painful swellings on distal legs and ventrum, skin then becomes thickened, lichenified, alopecic, and may fissure, ooze, scale, and crust |

NEOPLASTIC DISEASES

Lymphosarcoma (Lymphoma)

Signs

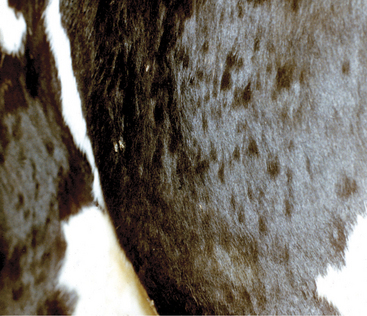

Diffuse nodular skin masses (1.0 to 10.0 cm in diameter) develop over the neck and trunk of young cattle with the skin form of lymphosarcoma. Lesions are initially dermal or subcutaneous, and the overlying skin appears normal. However, alopecia, crusting, hyperkeratosis, and ulceration develop with time. The tumors may become numerous enough to obliterate any normal skin spaces between them (Figure 7-9). Tumors may occur on the skin over any portion of the body. Peripheral lymph nodes are usually enlarged. The heifer or young cow seems otherwise healthy at the onset. However, over a period of 6 to 12 months, affected animals become uncomfortable because of the tumor burden, and visceral masses may develop. Fly and other insect irritation can be intense during warm weather, causing bleeding from the enlarging nodular tumors, which may have become alopecic (Figure 7-10). Most cases are BLV negative.

Fine needle aspirates or skin biopsies are the best means of definitive diagnosis for lymphosarcoma. Although advanced cases of the skin form are unlikely to require diagnostics, early cases with fewer lesions may require differentiation from other neoplasms and diseases such as urticaria and infectious or sterile granulomas.

Angiomatosis

Angiomatosis, although uncommon, is a cause for concern to owners of affected cattle because of the friable nature of the skin masses that predisposes to repeated bouts of hemorrhage that are dramatic given the small size (1.0 to 2.5 cm) of the tumors. Affected cattle tend to be mature with the average age reported to be 5.5 years.

Lipomatosis (Infiltrative Lipoma)

A rare condition in dairy cattle that may represent a hamartoma involving fat, lipomatosis appears as enlarging masses in the facial area or heavy muscles of the hind limbs (Figure 7-11). The masses may be so large as to interfere with function (e.g., mastication or respiration). They are fluctuant and soft on palpation, but attempts at fluid aspiration yield nothing. Fine needle aspirates or biopsy provides the diagnosis. No treatment exists because surgical removal is impossible as a result of infiltration of the fatty mass into musculature.

Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Signs

Clinical signs of a pink, cobblestone, raised or ulcerated mass arising from a depigmented area of skin are pathognomonic for squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 7-12). Frequently a white or yellow “cake frosting” of necrotic material covers the pink, highly vascular tumor surface, and an anaerobic or necrotic odor is detectable. Heavy purulent discharges make the tumors greatly attractive to flies and maggots. Biopsies are preferable to cytology for definitive diagnosis.

Treatment

Small squamous cell carcinomas are amenable to many treatment modes such as cryosurgery, radiofrequency hyperthermia, radiation, immunotherapy, or even sharp surgery. Each tumor must be evaluated by anatomic location, how much tissue may be destroyed without loss of tissue function (e.g., an eyelid), and expense of treatment. Treatment is addressed in detail in Chapter 13. In general, cryosurgery, radiofrequency hyperthermia, and radiation are the best treatments for small tumors and allow preservation of critical normal structures. Immunotherapy, especially with intratumor injections of Bacillus Calmette Guérin (BCG) or other mycobacterial cell wall products, will risk future tuberculosis tests being positive but may be helpful in large tumors. Other topical or intralesional treatments that are used in horses for sarcoids could be beneficial but no reports are available. Regional lymph nodes should be palpated and biopsied if they appear enlarged or firm, thus possibly indicating metastasis. Metastases have been reported to occur in about 10% of squamous cell carcinomas, but clinically, obviously neglected or large tumors are more likely to metastasize than early or small lesions.

Other Cutaneous Neoplasms and Nonneoplastic Growths

A number of neoplastic and nonneoplastic growths occur in the skin of cattle. A listing of these uncommon to very rare disorders is provided in Table 7-2.

TABLE 7-2 Miscellaneous Neoplastic and Nonneoplastic Growths

| Basal cell tumor | Adult to aged; solitary firm to fluctuant nodule; often alopecic and ulcerated; anywhere on body; benign |

|---|---|

| Trichoepithelioma | Adult to aged; solitary firm to fluctuant nodule; often alopecic and ulcerated; anywhere on body; benign |

| Sebaceous adenoma | Adult to aged; solitary nodule; anywhere on body (especially eyelid); benign |

| Sebaceous adenocarcinoma | Adult to aged; solitary nodule; anywhere on body (especially jaw); malignant |

| Epitrichial (apocrine) adenoma | Adult to aged; solitary nodule; tail; benign |

| Fibroma | Adult to aged; solitary, firm or soft, dermal or subcutaneous nodule; anywhere on body (especially head, neck, shoulder); benign |

| Fibrosarcoma | Adult to aged; solitary, firm or soft, dermal or subcutaneous nodule; anywhere on body (especially head, neck); malignant |

| Hemangioma | Adult to aged animals develop solitary, firm to soft, red to blue to black dermal nodules; anywhere on body (especially head, legs); benign; multiple lesions occur congenitally or in animals less than 1-year-old; may be accompanied by widespread internal lesions |

| Hemangiosarcoma | Adult to aged; solitary nodule, often necrotic, ulcerated, and bleeding; anywhere on body (especially leg); malignant |

| Hemangiopericytoma | Adult to aged; solitary nodule, anywhere on body (especially jaw); benign |

| Lymphangioma | Congenital or animals less than 1-year-old; solitary soft nodule; anywhere on body (especially leg, brisket); benign |

| Myxoma | Congenital to aged; solitary soft nodule; anywhere on body (especially pinna, leg); benign |

| Myxosarcoma | Adult to aged; solitary nodule; anywhere on body; malignant |

| Neurofibroma (Schwannoma; neurofibromatosis) | Congenital to adult; usually multiple firm papules and nodules; unilateral or bilateral; anywhere on body (especially muzzle, face, eyelids, neck, brisket); benign |

| Lipoma | Adult to aged; solitary subcutaneous nodule; anywhere on body (especially trunk); benign |

| Mast cell tumor | Adult to aged animals develop solitary or multiple papules and nodules that are often alopecic, erythematous, and ulcerated; anywhere on body; multiple lesions can be present congenitally on calves; 60% of animals with widespread lesions have metastases |

| Melanocytic neoplasms | All ages (>50% of cases in cattle <18 months old); about 80% of lesions are benign (melanocytoma), and 20% are malignant (melanoma); usually solitary dermal to subcutaneous nodules, gray-to-black in color, firm to fluctuant; anywhere on body (especially leg) |

| Dermoid cyst | Congenital; solitary nodule; especially dorsal midline of neck, eyelid, and periocular area; benign |

| Branchial cyst | Congenital; solitary firm to fluctuant swelling in ventral neck area; benign |

| Cutaneous horn | Adult to aged; hornlike hyperkeratosis, usually overlies squamous cell carcinoma or papilloma |

ALLERGIC OR IMMUNE-MEDIATED DISEASES

Urticaria, Angioedema, and Anaphylaxis

Etiology

Urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis are the most obvious clinical consequences of hypersensitivity reactions or “allergic” reactions. Urticaria (hives) appears as skin wheals or mucous membrane swellings as a result of dermal edema (Figure 7-13). Angioedema tends to imply larger swelling or plaques of edema that involve subcutaneous tissue. Anaphylaxis is the life-threatening extreme manifestation of these hypersensitivity reactions, and its rapid onset causes severe respiratory and cardiovascular signs resulting from smooth muscle contraction and vascular alteration. Anaphylaxis usually is fatal unless attended immediately and may or may not have urticaria and angioedema associated with it. A plethora of drugs, feeds, and other stimuli may evoke hypersensitivity reactions in calves and adult cattle. The exact immunologic phenomenon or type of hypersensitivity reaction (types I through IV) is sometimes difficult to determine, but most probably represent type I and type III hypersensitivity reactions. Type I hypersensitivities are IgE mediated, whereas type III are associated with immune complexes. Type I hypersensitivities cause mast cell and basophil degranulation with subsequent release of histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other mediators. Type I reactions probably provoke most ruminant causes of urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis. Type III reactions may include some drug-induced causes, but this conclusion is largely speculative.

Vaccines are the most common cause of anaphylaxis. Although serum origin products are used less frequently, many “antisera” are still available on the market, and these are especially dangerous as causes of both immediate and delayed hypersensitivity reactions. Polyvaccines have gained favor in the cattle industry, and it is not unusual to give a single shot that contains antigens of four viruses, five serotypes of leptospirosis, and a vehicle. Reactions to such polyvaccines make determining the causative antigen difficult. Strain 19 Brucella vaccine occasionally has caused either immediate or delayed hypersensitivity reactions. A rare reaction involves the larynx, causing severe laryngeal edema within 24 hours of strain 19 vaccine. Although some vaccines are more notorious than others as causes of anaphylaxis, any vaccine may cause occasional reaction. Various gram-negative bacterins containing slight amounts of bacterial-origin endotoxin can induce reactions that mimic anaphylaxis through a genetic sensitivity—especially in Holsteins. This theory may explain why reactions are seen in some herds but not in others.

Hypoderma larvae that are killed in situ have caused anaphylactic reactions or reactions to toxins that mimic anaphylactic reactions. Feeds certainly may cause hypersensitivity reactions in individual cattle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree