Chapter 83Skeletal Muscle and Lameness

Diagnosis of Specific Muscle Disorders in the Horse

Physical Examination

A detailed evaluation of the muscular system includes inspection of the horse for symmetry of muscle mass while standing with forelimbs and hindlimbs exactly square. Any evidence of fine tremors or fasciculations should be noted before palpating the horse. Horses originating in the southwestern United States that have muscle pain and fasciculations should have their ears examined with an otoscope for ear ticks (Otobius megnini).1 The entire muscle mass of the horse should be palpated for heat, pain, swelling, or atrophy comparing contralateral muscle groups. Firm, deep palpation of the lumbar, gluteal, and semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles may reveal pain, cramps, or fibrosis. The triceps, pectoral, gluteal, and semitendinosus muscles should be tapped with a fist or percussion hammer and observed for a prolonged contracture suggestive of myotonia. Running a blunt instrument such as artery forceps, a needle cap, or a pen over the lumbar and gluteal muscles should illicit extension (swayback), followed by flexion (hogback) in healthy horses. Guarding against movement may reflect abnormalities in the pelvic or thoracolumbar muscles, or pain associated with the thoracolumbar spine (see Chapter 52) or sacroiliac joints (see Chapter 51). The horse should be observed at the walk and the trot for any gait abnormalities, and some horses should be ridden.

Ancillary Diagnostic Tests

Muscle Enzymes

Nuclear Scintigraphy

Technetium-99m–methylene diphosphonate (MDP) is taken up in some damaged muscle in the horse and is best seen in the bone (delayed) phase images, that is, 3 hours after injection. Scintigraphy has been used most commonly in horses with a history of poor performance, with or without stiffness after exercise, to confirm a diagnosis of equine rhabdomyolysis.16 The mechanism of MDP binding is unknown, but the release of large amounts of calcium from damaged muscle or the exposure of calcium binding sites on protein macromolecules in the damaged muscle may be responsible. Diffuse linear areas of increased radiopharmaceutical uptake (IRU) are commonly seen in the caudal epaxial muscles and the muscles of the hindquarters and thigh in some but not all horses with ER (Figure 83-5). Less commonly there is IRU in the triceps and latissimus dorsi muscles.

Muscular Pain, Strain, and Tears

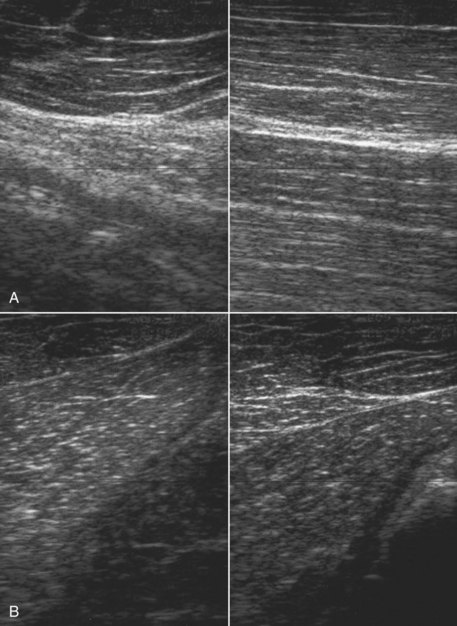

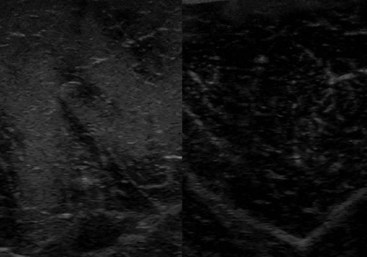

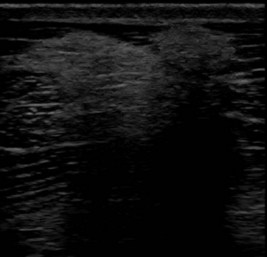

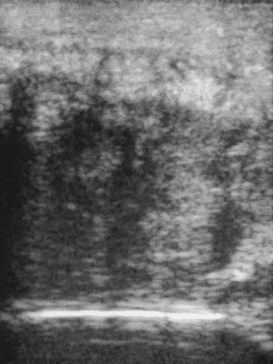

Muscle fibrosis and mineralization have been well documented in the horse following tearing of the semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles (see Fibrotic Myopathy section, page 558), but acute lesions here and elsewhere in the limbs have been poorly documented.27-29 The use of diagnostic ultrasonography17,18 has helped in the diagnosis of both acute and more chronic muscle lesions, but diagnosis often remains a challenge because of the deep location of some affected muscles and the lack of localizing clinical signs.

In one author’s (SJD) experience, the most commonly recognized muscle injury sites in the forelimb include biceps brachii, brachiocephalicus, the pectorals, and the musculotendonous junction of the superficial digital flexor (Figures 83-1 to 83-4). In the hindlimb, semimembranosus and semitendinosus, adductor, gracilis, gluteal, and gastrocnemius muscle injuries have been recognized most frequently. Acute muscle tearing and hemorrhage can result in severe pain and lameness and other clinical signs mimicking colic. Swelling around the damaged muscle, assuming it is superficial, may not appear until 24 to 48 hours later.

Muscle tension and spasm in the thoracolumbar region are well-documented sources of pain contributing to poor performance in association with primary hindlimb lameness, but primary muscle pain in this region has often tended to be overlooked by many veterinarians, although recognized by physiotherapists. Localized muscle soreness and the interpretation of abnormal sensitivity of acupuncture points are potentially confusing. Protective muscle spasm may also develop secondary to a primary lesion of either the thoracolumbar spine or the sacroiliac region (see Chapters 49 to 52).

Localized back muscle soreness is readily induced by a poorly fitting saddle. It may also be caused by a rider who either sits crookedly or is unable to ride completely in balance with the horse. This may be because of the ineptitude of the rider or the shape of the saddle and the way in which it sits on a particular horse and thus positions the rider. Such muscle pain is usually localized to the saddle area and may be associated with slight soft tissue swelling. Thermographic examination may be helpful to demonstrate to an owner the associated localized inflammation. Pressure measurements can also be used (see Figure 117-6), although there is some variability in the accuracy of different commercially available systems.

Diagnosis

History and Clinical Examination

The neck, limbs, and thoracolumbar region should be moved passively to detect any limitations in movement or pain induced by movement. The horse should be observed moving at both the walk and the trot to identify any characteristic gait abnormalities, such as an abnormal hind foot placement from fibrotic myopathy (see Chapter 48) or sinking of a front fetlock as a result of rupture at the musculotendonous junction of the superficial digital flexor (see Chapter 13)![]() . However, it must be borne in mind that muscle soreness resulting in compromise of performance may not result in overt lameness because pain may only be induced when the muscle contracts strongly or is stretched maximally. Pain associated with a brachiocephalicus muscle in a dressage horse may only be evident in particular movements such as half pass (see Figure 83-3). A show jumper with sore gluteal muscles may not push off as strongly with the affected limb, resulting in the hindquarters drifting toward the ipsilateral side as the horse jumps.

. However, it must be borne in mind that muscle soreness resulting in compromise of performance may not result in overt lameness because pain may only be induced when the muscle contracts strongly or is stretched maximally. Pain associated with a brachiocephalicus muscle in a dressage horse may only be evident in particular movements such as half pass (see Figure 83-3). A show jumper with sore gluteal muscles may not push off as strongly with the affected limb, resulting in the hindquarters drifting toward the ipsilateral side as the horse jumps.

Thermography, Nuclear Scintigraphy, and Ultrasonography

Thermography, nuclear scintigraphy, and ultrasonography are discussed on pages 819 and 820.

Treatment

The aims of treatment include repair of damaged muscle, relief of both muscle spasm and pain, restoration of normal circulation, minimization of fibrous scar formation, and remobilization of muscles. The precise mode of treatment will depend on the type of muscle injury and the stage of injury and repair. Treatment modalities include laser,31,32 therapeutic ultrasound,31 H wave, transcutaneous electrical stimulation, electromagnetic therapy,33 massage,26 passive stretching combined with box rest, and a graduated, controlled exercise program. Relief of acute muscle spasm may require chiropractic manipulation. During return to work, the exercise program must be carefully moderated according to the site of the injury and to avoid overstress in the early stages of repair while encouraging a progressive increase in strength. These subjects are discussed more fully elsewhere (see Chapters 92 through 96).

] is 108 min).4 A threefold to fivefold increase in serum CK from normal values is believed to represent necrosis of approximately 20 g of muscle tissue.5 Rhabdomyolysis results in a proportionately greater increase in the MM isoform than the MB isoform, although some investigators disagree with the tissue specificity of serum CK isoforms in the horse.6 Limited elevations in CK (<1000 U/L; high range of normal value = 380 U/L ) may accompany training or transport.7 Extreme fatiguing exercise (e.g., endurance rides or the cross-country phase of a Three Day Event) may result in CK activities being increased to more than 1000 U/L, but usually less than 5000 U/L. Under these circumstances, serum CK activities rapidly return to baseline (i.e., <350 U/L in 24 to 48 hours). Recumbent horses also may have slightly elevated CK activities that are usually less than 3000 U/L. In contrast, more substantial elevations (from several thousand to hundreds of thousands of units per liter) in the activity of this enzyme may occur with rhabdomyolysis.3

] is 108 min).4 A threefold to fivefold increase in serum CK from normal values is believed to represent necrosis of approximately 20 g of muscle tissue.5 Rhabdomyolysis results in a proportionately greater increase in the MM isoform than the MB isoform, although some investigators disagree with the tissue specificity of serum CK isoforms in the horse.6 Limited elevations in CK (<1000 U/L; high range of normal value = 380 U/L ) may accompany training or transport.7 Extreme fatiguing exercise (e.g., endurance rides or the cross-country phase of a Three Day Event) may result in CK activities being increased to more than 1000 U/L, but usually less than 5000 U/L. Under these circumstances, serum CK activities rapidly return to baseline (i.e., <350 U/L in 24 to 48 hours). Recumbent horses also may have slightly elevated CK activities that are usually less than 3000 U/L. In contrast, more substantial elevations (from several thousand to hundreds of thousands of units per liter) in the activity of this enzyme may occur with rhabdomyolysis.3 is 7 to 10 days).4,8

is 7 to 10 days).4,8