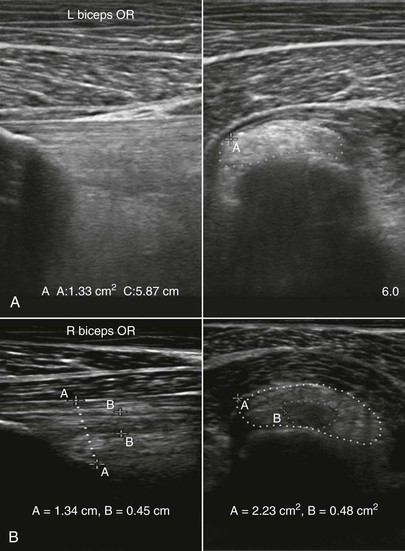

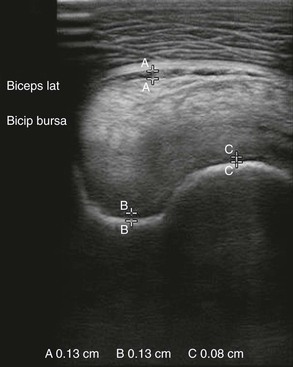

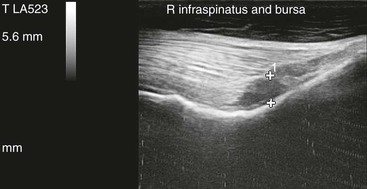

Carol L. Gillis Because of its prominent location on the point of the shoulder, the biceps brachii tendon is the most commonly injured structure of the shoulder soft tissues. Unlike most tendons and ligaments, the biceps tendon is often injured as a result of direct trauma rather than cumulative overload. The medical history often includes the horse being kicked while breeding or being ridden, or hitting a fence or other solid object with the affected shoulder. Athletic use overload also occurs. Rarely, the biceps tendon is injured, or bicipital synovitis develops secondarily to developmental orthopedic disease of the humeral tubercles. Synovitis of the bicipital bursa may occur alone or in conjunction with damage to the biceps tendon. Horses with bicipital bursitis or biceps tendonitis resent palpation of the tendon and pressure applied to the front of the shoulder. If the horse is asked to walk and then halt, it often prefers to stand with the affected limb placed slightly caudal to the unaffected one. The supraspinatus muscle is also prominently placed on the humeral tubercles, and injury of this muscle also should be suspected with the previously described injury history. Clinical signs are similar to those seen with biceps tendon injury. The infraspinatus muscle and its bursa are often injured when the lower limb is abruptly or excessively adducted, such as when a Western event horse or a polo pony suddenly changes direction while traveling at high speed. Pain on palpation of the muscle and on limb adduction or abduction are the usual clinical signs. The primary imaging modality for diagnosis of muscle, tendon, and bursa injuries is ultrasonography. A high-frequency linear transducer (7 to 12 MHz) is ideal for the examination. The shoulder area should be clipped (except for very short-haired horses) and washed with mild soap and water, after which ultrasound gel is applied. The tendinous origin of the bicipital muscle is located on the craniodistal aspect of the distal part of the scapula, and it is important to begin the exam at this location (Figure 188-1). The tendon is evaluated in long- and short-axis planes as it traverses the humeral tubercles and joins the muscle distally. At the level of the humeral tubercles, the most common site of injury, the tendon is bilobed; each lobe may need to be evaluated separately because of size. The usual ultrasonographic parameters of size, echogenicity, and fiber pattern should be used to determine whether injury has occurred. The deep edge of the tendon is normally hypoechoic as it undergoes compression by the humeral tubercle, which results in it having a fibrocartilaginous component. This creates two diagnostic challenges. The first is to determine whether the hypoechoic region is normal, either through practice in the use of ultrasound or by comparison with the opposite tendon. The second is to differentiate the hypoechoic tendon from the fluid contents of the bicipital bursa. This can best be achieved by changing the transducer angle slightly until the bursa sheath can be detected. The bursa normally contains less than 3 mm depth of hypoechoic to anechoic fluid (Figure 188-2). With inflammation, the bursa initially distends with effusion, with first synovial proliferation and finally adhesions developing over time in the absence of treatment. The bursa may be injected under ultrasound guidance, with a The supraspinatus muscle is examined in short- and long-axis views from its origin in the supraspinous fossa to its tendinous portion, which bifurcates to insert on the humeral tubercles medial and lateral to the biceps tendon. The infraspinatus muscle is examined from its origin in the infraspinous fossa to its tendinous portion, which splits into deep (short) and shallow (long) insertions on the lateral aspect of the humerus. The infraspinous bursa is evaluated for volume and character of fluid (Figure 188-3).

Shoulder Injuries

Soft Tissue Injuries of the Shoulder

History and Clinical Signs

Diagnosis

-inch, 19-gauge needle used to access either the shallow part of the sheath lateral to midline or the lateral part of the bursa between the lateral lobe of the biceps tendon and the axial border of the cranial greater humeral tubercle. A volume of 15 to 20 mL of local anesthetic should be injected to sufficiently anesthetize the structure and confirm that it is the source of pain. In less than 20% of horses, the bursa communicates with the shoulder joint, so the response to anesthesia must be interpreted in conjunction with ultrasonographic findings. Distal to the humeral tubercles, the muscular portion of the biceps tendon is examined in both planes to the point of its short tendinous insertion.

-inch, 19-gauge needle used to access either the shallow part of the sheath lateral to midline or the lateral part of the bursa between the lateral lobe of the biceps tendon and the axial border of the cranial greater humeral tubercle. A volume of 15 to 20 mL of local anesthetic should be injected to sufficiently anesthetize the structure and confirm that it is the source of pain. In less than 20% of horses, the bursa communicates with the shoulder joint, so the response to anesthesia must be interpreted in conjunction with ultrasonographic findings. Distal to the humeral tubercles, the muscular portion of the biceps tendon is examined in both planes to the point of its short tendinous insertion.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Shoulder Injuries

Chapter 188

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue