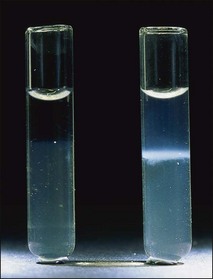

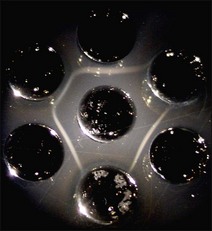

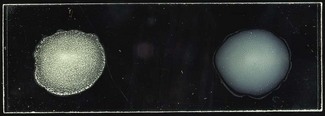

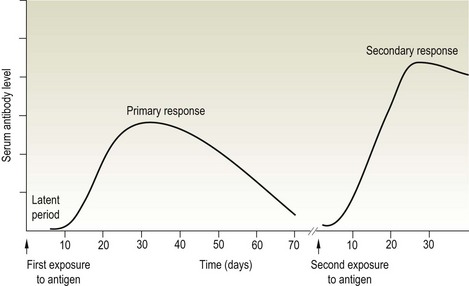

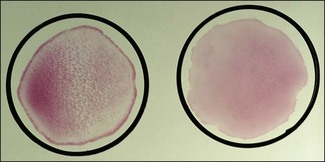

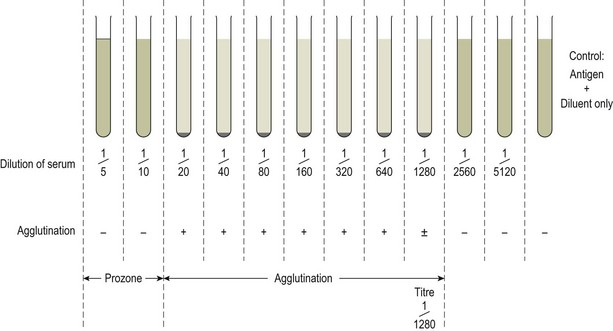

Chapter 3 Serological testing is generally less expensive and easier to perform than the isolation or detection of an infectious agent, particularly virus. Clinicians often request serological screening as the first step in a disease investigation. Serology testing only requires clotted blood samples which are relatively easy to collect from large numbers of animals. Many of the classic serology techniques have been employed for decades and have a proven track record in the field. They are very reliable and the results are accepted internationally. Traditional serological diagnosis of infection is based upon identification of specific antibody. When an animal encounters an infectious agent or foreign substance for the first time, antibody to that agent or substance is usually (but not always) detectable in the serum within 10–14 days. The time required for antibody production is influenced by the nature, amount and route of exposure to the agent, the age and immune status of the animal and the sensitivity of the assay used to demonstrate circulating antibody. For some infectious organisms the production of detectable antibody may take considerably longer than 14 days, for example, antibodies to equine infectious anaemia virus may not be detected for more than 60 days post exposure. The first antibody response to antigen is referred to as the primary response. The interval between exposure and production of antibody is referred to as the latent period (or lag period). If exposure to the same antigen occurs again some time later, the animal responds with a stronger and more sustained response and the latent period is shorter due to the presence of memory B cells. This is termed the secondary response (Fig. 3.1). The memory response of an animal for an agent it has previously been exposed to is called the anamnestic response. Figure 3.1 A comparison of specific antibody production during primary and secondary responses to infectious agents or to vaccination. Natural infection usually results in higher levels of antibody for a longer time period. Many of the immunological techniques described below can be used to detect antibody or antigen (see also Chapter 5). When soluble antigen is added to homologous antibody at the correct ratio insoluble antigen–antibody complexes are formed. If the immune complexes are of sufficient size they precipitate out of solution. This form of immunological precipitation is termed the precipitin reaction. When diluted antigen is layered carefully over homologous antibody a band of precipitate forms where the ratio of the reagents is at optimal proportions. This method is termed the ring precipitin test (Fig. 3.2) and has found application in identifying streptococci and assigning them to their appropriate Lancefield groups. A limitation of this method is the requirement for high levels of antibody in the antiserum employed. Precipitation reactions can take place in semisolid media such as agar gels. When soluble antigen and antibodies are placed in wells cut in a gel, they diffuse towards each other and where they meet at or near optimal proportions, a precipitin line forms in the gel. Immunodiffusion in agar (Fig. 3.3) is applied in diagnostic tests for infectious diseases particularly in virology and the Coggins test for equine infectious anaemia is based on this method. The agar gel immunodiffusion test for caprine arthritis/encephalitis and for maedi-visna or ovine progressive pneumonia is a cost-effective method of identifying persistently infected carriers and is the prescribed test for international trade. It is also the traditional test for the detection of antibody to virus-infection-associated antigen (VIAA) of foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) virus and has been used extensively in FMD eradication in South America. An agglutination reaction occurs when antibody reacts with particulate antigen and cross-links surface antigenic determinants. Bacteria, fungi, protozoa and red cells can be directly agglutinated by specific antibody. One drop of test serum is added to a standardized suspension of bacteria on a slide. After gentle rocking the result is read inside three minutes. In the presence of antibodies, the antigens are agglutinated (Fig. 3.4). Occasionally bacteria or other antigens may be deliberately coloured to facilitate interpretation of the result and, in addition, in the Rose Bengal agglutination test for Brucella abortus, the pH of the suspending fluid is dropped to a low level to eliminate nonspecific agglutination and improve the reliability of the test (Fig. 3.5). The slide agglutination test is also used to demonstrate the presence of antibody in serum. Figure 3.5 Rose Bengal plate agglutination test for Brucella abortus (coloured antigen): positive reaction (left) and negative reaction (right). Quantitative agglutination can be performed in test tubes or microtitre plates by serially titrating the serum under test, usually in twofold dilutions. An equal volume of standardized antigen, such as bacteria, is added to each tube and a control tube with diluent. Following careful mixing the tubes are incubated, usually at 37°C. Results are recorded after a few hours and the highest dilution of the serum giving agglutination is called the antibody titre (Figs 3.6 and 3.7). For diagnostic purposes, two blood samples taken several weeks apart should be used to demonstrate a rising titre in infected animals. Figure 3.6 Interpretation of the tube agglutination test. Tubes with high levels of antibody, where agglutination does not occur, represent a prozone effect.

Serological diagnosis

Precipitation

Agglutination

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Serological diagnosis

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue