CHAPTER 18 Seizure Disorders

Narcolepsy

DEFINITION

The terms seizure, convulsion, epilepsy, and fit are synonyms for a brain disorder expressed as a paroxysmal transitory disturbance of brain function that has a sudden onset, ceases spontaneously, has a tendency to recur, and originates in the prosencephalon. The term epilepsy is usually used for seizures that are recurrent. Those of unknown cause are called idiopathic epilepsy. The initial seizure focus may involve only a small number of highly unstable neurons that spontaneously discharge. This first episode may induce surrounding neurons to discharge, resulting in a progressive spread, or generalization, of the seizure. The pathogenesis of seizures has been and still is currently the subject of extensive investigation.*

TERMINOLOGY

Postictal depression refers to the period of recovery after a seizure when the patient may wander around in a state of confusion, may propulsively walk in circles or bump into objects because of its central blindness, or may sleep for a prolonged period or exhibit hyperphagia. This phase has the appearance of a patient whose neurons are exhausted from the excessive activity of the seizure. The length and form of postictal depression are variable. No correlation exists between the severity and length of the seizure and the severity, duration, or nature of the postictal phase. A short partial seizure may be followed by a longer, more complex postictus than a generalized seizure. As a rule, the postictal phase lasts less than an hour, but much longer periods of up to 1 to 2 days are possible. In horses, the postictal phase may last for 3 to 4 days.

An isolated seizure is a seizure that occurs only once in a 24-hour period. Cluster seizures are when two or more seizures occur in 24 hours separated by normal interictal periods. Status epilepticus is when the seizure state is continual for more than 5 minutes or when a series of seizures occur without full recovery of consciousness between the seizures for 30 minutes.5,93 The seizure is continually repeated with no interictal period. Cluster seizures and status epilepticus are medical emergencies.

CLASSIFICATION

PATHOGENESIS

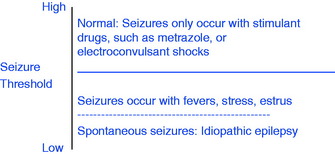

To understand the basis for seizures, consider that neurons have what we call a seizure threshold. This neuronal threshold is determined by their environment, which is genetically determined. Seizures result when this neuronal environment is disturbed and the threshold is lowered. Most commonly, the seizure originates in disturbed prosencephalic neurons. Consider this neuronal threshold in the following simple graph diagram.

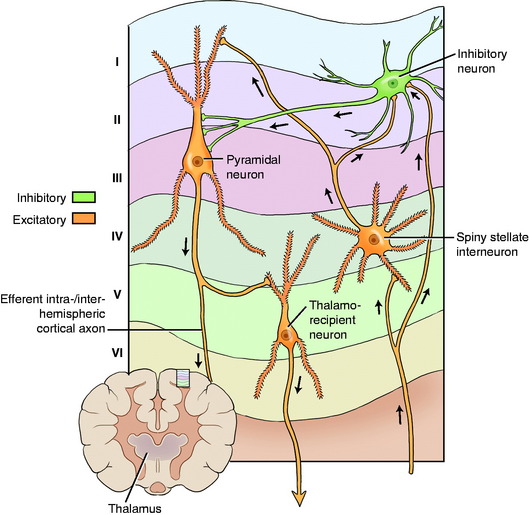

What comprises this neuronal environment? This concept is obviously very complex, but at the least it includes (1) the structure of the dendritic zones and all their synapses, as well as those on the neuronal cell body; (2) the neuronal lipoprotein cell membrane, including the plethora of ion channels that are influenced by the neurotransmitters and the enzymes involved with their activity, such as sodium-potassium-adenosine triphosphatase; (3) the ionic environment of the neurons that includes the availability of sodium, chloride, calcium, and potassium; and (4) the concentration of neurotransmitters that includes those concerned with excitation—glutamate, aspartate, and acetylcholine—and those concerned with inhibition—gamma aminobutyric acid, glycine, taurine, and norepinephrine. In addition, this neuronal environment includes the adjacent neurons and the astrocytes, which also have synapses with neurons and other astrocytes. Astrocytes regulate the transfer of metabolites and ions through the blood vessel walls and have a role in metabolizing many of the neurotransmitters.73Fig. 18-1 will help you appreciate the anatomic background of this neuronal environment. Alteration of any one or more of these components may lower the neuronal threshold enough to precipitate a seizure. These alterations comprise the differential diagnosis for seizures.

Figure 18-1 Neocortex showing some of the cellular components of the neuronal environment where seizures are initiated.

From: March PA: Seizures: Classification, etiologies, and pathophysiology, Clin Tech Sm Anim Pract 13:119–131, 1998.

Intracranial Disorders

Intracranial in this discussion refers to structural disorders.101 A thorough neurologic examination will often reveal one or more neurologic deficits in the interictal examination, which indicates a structural lesion.

Extracranial Disorders

Idiopathic Epilepsy

Idiopathic epilepsy, the most common cause of seizures in dogs,* is a syndrome characterized by repeated episodes of seizures for which no known demonstrable clinical or pathologic cause has been found. It is a diagnosis based on exclusion of all known causes of seizures. The interictal physical and neurologic examinations are normal, as are the blood studies, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) evaluation, and imaging studies that rule out the intracranial and extracranial disorders that can cause seizures. Some of these patients may show an abnormality in their EEG readings during the interictal period, but this does not have diagnostic value. Much to the dismay of the owner of a patient with seizures, no conclusive diagnostic test is available for this disorder. In patients with idiopathic epilepsy, the alteration of the neuronal environment in the prosencephalon that lowers their threshold for seizures cannot be recognized by any laboratory procedure or microscopic examination of the brain. The development of this seizure threshold is likely genetically determined. The assumption is that dogs with idiopathic epilepsy have a lowered threshold as a result of a genetic alteration that may be inherited. Pedigree analysis and breeding studies have determined an inherited epilepsy in a large number of breeds that include the following: German shepherd (Alsatian),39 Belgian Turvuren,126 keeshond, beagle,35 English springer spaniel,107 dachshund, vizsla,108 Bernese mountain dog,66 Irish wolf hound,24 Finnish spitz,127 golden retriever,122 standard poodle,75 and Labrador retriever.15 The incidence is high in many other breeds that may yet be proven to be inherited, and idiopathic epilepsy also occurs in mixed-breed dogs. Where data is sufficient, it supports an autosomal recessive or polygenic recessive inheritance.

In idiopathic epilepsy, the seizures are usually generalized, but a variety of partial forms do occur. The onset of seizures is usually between 6 months and 6 years of age, but both younger and older onsets have been recognized. Owners may recognize a prodrome that is some subtle change in the behavior of their dog just before the seizure. The seizure usually lasts from 30 seconds to 3 minutes. If the seizure is a partial seizure, the form it takes is consistent and does not usually vary in an individual dog. Large breeds such as the German shepherd, Saint Bernard, and Irish setter often have very severe generalized seizures that may occur in clusters. Miniature and toy poodles may exhibit a mild form of generalized seizure but without loss of consciousness. They act disoriented and exhibit some loss of balance as they develop spasticity of their neck, trunk, and limbs and uncontrolled diffuse trembling but still try to move close to their owners. Their seizure may last for up to 30 minutes. We often see simple partial seizures in Labrador retrievers that we diagnose as idiopathic epilepsy. Idiopathic partial seizures are recognized in Finnish spitz dogs with normal magnetic resonance (MR) imaging127 and are documented in the standard poodle as an autosomal recessive inherited disorder.75 Most dogs with idiopathic epilepsy are depressed and occasionally blind in the immediate postictal period, which usually lasts for less than an hour. The interval between seizures varies from one or a few weeks to months. The frequency of the seizures may increase as the dog ages, and the dog may occasionally develop status epilepticus during which death can occur. In many of these dogs, the seizures can be controlled to an acceptable level for the owner with the use of anticonvulsant therapy.

Idiopathic epilepsy is a diagnosis of exclusion in which MR imaging plays a significant role in demonstrating the lack of structural lesions in the prosencephalon. However, dogs with presumptive idiopathic epilepsy occasionally have lesions on MR imaging that are likely the effect rather than the cause of the repetitive seizures. These dogs may have bilaterally symmetric to asymmetric lesions in the piriform lobe, the adjacent hippocampal portion of the temporal lobe, or both.3,40,83 Similar lesions have been reported in the frontal and parietal lobes and less commonly in the cingulate gyrus and the thalamus. The lesions are typically hypointense on T1-weighted images, hyperintense on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery (FLAIR) images, and may or may not have scant contrast enhancement. The margins are not well demarcated, and they lack any mass effect. These lesions are usually transient and not visible on repeat imaging once seizure control is achieved. On microscopic examination, these lesions consist of edema, vascular proliferation, neuronal loss, reactive astrogliosis, and occasionally necrosis. Similar findings are reported in humans and are presumed to be related to the excitotoxic effect of accumulated glutamic acid.

Idiopathic epilepsy occurs in cats but is much less common.12,67,70 It is uncommon in farm animals2 and the horse, except for the Arabian foals; an idiopathic seizure disorder occurs in Arabian foals.1 The onset is 3 to 9 months of age, and after a period of weeks the seizures may spontaneously cease. A familial basis is suspected. A form of idiopathic epilepsy has been observed in horses that may be related to the estrus period when the estrogen levels are increased. The horse in the introductory Video 18-1 for this chapter had seizures that occurred only in the first few weeks after foaling. A postpartum hormonal irregularity was presumed to be responsible, given that no lesions were found in the brain after euthanasia and necropsy when the horse was 10 years old. Occasionally, one or more seizures may occur in a patient over a few days with no identifiable cause and then cease spontaneously, which can occur at any age in dogs but more commonly occurs in puppies.

EXAMINATION

Signalment

Age

Breed

Hypoglycemia of toy-breed puppies, hydrocephalus in toy and brachycephalic breeds, portosystemic shunt in Yorkshire terriers, neoplasm in boxers, idiopathic epilepsy in German shepherds and other breeds at risk (see earlier discussion), leukodystrophy in cairn and West Highland white terriers, neuronal storage disease in specific breeds (see Table 14-2), lissencephaly in the Lhasa apso, hyperlipidemia in miniature schnauzers, necrotizing meningoencephalitis in pug dogs, necrotizing leukoencephalitis in Yorkshire terriers

History

Onset and Course

An explosive onset of cluster seizures or status epilepticus can occur with neoplasms, intoxications, or occasionally idiopathic epilepsy. A progressive course with increasing frequency and duration of seizures occurs with inflammations or neoplasms. Regular intervals are more common in idiopathic epilepsy. Hypoglycemic seizures often occur just before or shortly after feeding. Seizures often follow a high-protein meal in hepatic encephalopathy.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Neurologic Examination

To be reliable, the examination must be performed in the interictal period. Abnormalities in the interictal neurologic examination suggest intracranial structural brain disease. Focal clinical signs suggest a neoplasm, vascular compromise, previous injury, or focal infection (granuloma, abscess). See Chapter 14 for the discussion of prosencephalic disorders and the three clinical signs that can be recognized in your neurologic examination indicating a prosencephalic dysfunction. Recognition of any one of these in an otherwise normal patient is critical for the diagnosis of a structural lesion that is the cause of the seizures. See Video 14-6 and Video 14-7 that follow Case Example 14-5 in Chapter 14, in which seizures were the chief complaint. Patients with frontal lobe lesions may circle toward the side of the structural lesion (the adversive syndrome). This is a common clinical sign that helps locate the side of a prosencephalic disorder. Multifocal clinical signs suggest an inflammation or multiple neoplasms. Clinical signs of diffuse prosencephalic or brain dysfunction may occur with inflammations, degenerative diseases, or a metabolic disorder that is neuronal or extracranial in origin.

Further study to determine the cause of the seizure requires ancillary examinations.

Ancillary Examination

Blood Chemistry

The blood urea nitrogen (BUN) may be increased in chronic renal disease or decreased with portosystemic shunts. Most animals with hepatic encephalopathy will be hyperammonemic and show variable evidence of liver dysfunction on serum studies. Hypoglycemia or abnormal glucose-to-insulin ratios may be diagnostic for a pancreatic beta-cell neoplasm or other disease process. Electrolyte abnormalities may be recognized. Bile acid evaluation will be abnormal with diffuse liver disorders such as the portosystemic shunt. Hyperlipidemia may relate to seizure genesis.

Signalment: 6-year-old female Boston terrier

Anatomic Diagnosis: Diffuse brain but primarily the prosencephalon bilaterally

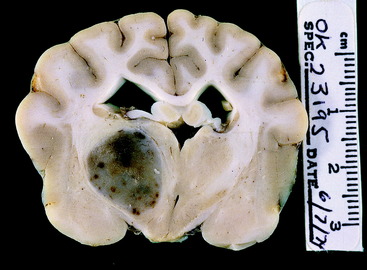

The patient was euthanized, and necropsy revealed a well-defined astrocytoma in the left side of the diencephalon at its junction with the telencephalon (Fig. 18-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree