Warren Beard

Scrotal Hernia in Stallions

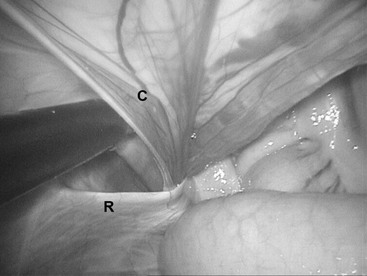

The inguinal canal is an oblique passage through the abdominal wall through which all testicular structures pass. The superficial opening of the inguinal canal is a slit in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle termed the superficial inguinal ring. The deep inguinal ring is formed by the internal abdominal oblique muscle, the rectus abdominis muscle, and the inguinal ligament. Entrance into the inguinal canal is through the vaginal ring, a slitlike opening formed as the parietal peritoneum everts through the deep inguinal ring to become the parietal vaginal tunic. Scrotal herniation occurs when the vaginal ring is large enough to permit entry of abdominal viscera, usually small intestine, into the vaginal tunic. The terms scrotal hernia and inguinal hernia are often used interchangeably. The vaginal ring normally fits snugly around the testicular structures that traverse the inguinal canal (Figure 154-1). On palpation per rectum, the slitlike opening of the vaginal ring should be no more than two fingers wide, and the examiner should not be able to fully insert two fingers into the inguinal canal. A vaginal ring that freely permits the passage of two fingers should be considered enlarged and the horse at risk for developing a scrotal hernia. There is a general consensus that draft breeds and Standardbred horses are predisposed, although regional prevalence is likely to reflect the local horse population. A discussion with the owners on the heritability of the condition should take place before surgery to determine whether the owners wish to perform a unilateral or bilateral castration or to keep the horse intact. Some owners may elect to castrate affected horses, whereas others will insist the horse remain intact. A scrotal hernia may be either strangulating or nonstrangulating, and strangulating scrotal hernias may be manually reducible or not. The combination of these factors creates a variety of clinical presentations that affect the decision-making process, treatment options, and prognosis.

Nonstrangulating Scrotal Hernia

A nonstrangulating scrotal hernia is generally the result of a congenital inguinal hernia that did not spontaneously resolve and was left untreated. Such cases are relatively uncommon, but they do exist. Palpation of the scrotum in the standing horse before general anesthesia for castration is essential to identify such horses because the herniated small intestine will spontaneously reduce when the horse is anesthetized, and many of these horses will eviscerate after standing. The risk for evisceration is greatly diminished by use of a closed castration technique, with a ligature placed around the parietal vaginal tunic (Figure 154-2). It would be unusual for a congenital inguinal hernia to be left untreated in a horse that the owners intended to keep as a stallion. Should that scenario arise, laparoscopic imbrication of the vaginal ring would likely be the treatment of choice.

Evisceration Following Castration

Evisceration occurs when the jejunum passes through the vaginal ring and the open scrotum is unable to contain the jejunum. It is an infrequent complication following castration in most breeds and typically occurs in the first few hours following castration. Standardbreds and draft horses appear to be predisposed, given the higher incidence of congenital inguinal hernias in these breeds; one report cites the incidence as 4.8% of castrations in draft colts. Horses may panic and kick at the eviscerated bowel, and the mesenteric attachments may be avulsed because of trauma and the sheer weight of the eviscerated jejunum. Evisceration is a life-threatening emergency, and immediate and appropriate intervention is necessary for the horse’s survival.

The horse should be quickly moved to a clean environment and reanesthetized. Ideally, definitive repair should happen at this time. In reality, this seldom occurs because horses are usually castrated in a field setting without the facilities, equipment, or persons with the technical expertise necessary to perform a laparotomy and possibly a resection and anastomosis. The jejunum should be copiously washed and the presence of an intact mesenteric blood supply confirmed before the bowel is replaced in the scrotum. The scrotal incision can be sutured or towel-clamped closed before anesthetic recovery and transport to a surgical facility (Figure 154-3). Broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy should be initiated at this time. Prompt surgery is still required because the bowel, although contained within the scrotum, is still strangulated at the vaginal ring.

If the bowel and vascular supply are intact, definitive therapy consists of copiously lavaging the bowel and replacing it into the abdomen through the parietal vaginal tunic. This is most easily accomplished through a separate approach immediately overlying the superficial inguinal ring. The vaginal tunic must be identified and held by stay sutures or tissue forceps, and the bowel replaced into the abdomen through the vaginal tunic. This can be facilitated by digital enlargement of the vaginal ring. It is important that the bowel is replaced through the vaginal ring and that care is taken to avoid grasping loops of bowel and replacing them in the abdomen through a separate portal. The latter method results in bowel leaving the abdomen through the vaginal ring and entering the abdomen through a separate peritoneal perforation and still strangulated around a band of inguinal fascia. The inguinal canal may be packed with gauze for 24 hours, by which time inguinal edema will prevent recurrence. Alternatively, the superficial inguinal ring may be sutured.

If the bowel or the mesenteric blood supply is damaged, or the bowel cannot be replaced by the previously described method, a ventral midline laparotomy must be performed. The bowel is replaced by combined gentle manual traction at the vaginal ring with help from an assistant pushing the bowel from the inguinal approach. A small intestine resection and anastomosis are performed, if necessary. The inguinal approach is closed by one of the methods described previously, and the laparotomy is closed in routine fashion.

Individual circumstances are more important in formulating a prognosis than reliance on published reports. The duration of evisceration, appropriate first aid, proximity of surgical facilities, technical expertise, length of affected bowel, and presence of self-trauma all influence the prognosis. Horses receiving prompt, appropriate treatment can have a good prognosis. Horses in which scrotal herniation was unobserved initially may be trailing intestine on the ground at the time of discovery and be candidates for immediate euthanasia. Reported long-term survival rates range from 44% to 87% under widely varying circumstances.

Strangulating Scrotal Hernias

A strangulating scrotal hernia develops when small intestine enters the vaginal tunic and occludes blood flow to both the intestine and the testicle. Signs of colic are immediate and severe. Clinical signs are typical of a strangulating small intestine lesion and include tachycardia, dry mucous membranes, high hematocrit and plasma protein concentrations, progressive fluid distension of the small intestine, and ultimately nasogastric reflux. Progressive metabolic deterioration ensues because of loss of fluid from the vascular space into the small intestine. Scrotal herniation should be a differential diagnosis in any stallion with colic. In contrast to most other strangulating small intestine lesions, it can be diagnosed with certainty by palpation of the vaginal ring per rectum. The examiner will find a loop of bowel entering the vaginal ring by sweeping a hand across the caudal abdominal wall ventral to the pelvic brim. Additionally, the enlarged spermatic cord can be palpated externally on the affected side (Figure 154-4). The spermatic cord in a normal testicle can be clearly palpated from the cranial pole of the testicle to the superficial inguinal ring. In affected testicles, the spermatic cord is turgid, enlarged enough to obscure the demarcation between spermatic cord and testicle, and painful and cold to the touch. These characteristic abnormalities are easily detected, but only if one specifically checks for them. They are often overlooked by casual examination and will always be missed by failure to check.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree