Chapter 1

Sample Collection and Preparation

Collection and preparation of cytologic specimens is definitely a skill gained only through experience and refinement of technique based on the results obtained. Many clinicians (and owners) are understandably frustrated when a sample submitted is determined to be nondiagnostic. Fortunately, an understanding of some basic principles of sample collection and familiarity with some of the more common pitfalls related to cytologic sample preparation can increase the odds of a diagnostic result.1–5

Methods of Sample Collection

Several methods of collecting samples for cytologic analysis exist. The indications for each are outlined in Table 1-1.

TABLE 1-1

Indications for Various Methods of Sample Collection

| Collection Method | Indications for Uses | Comments |

| Fine-needle biopsy (aspiration or nonaspiration method) | Masses (surface or internal) | Best method for cutaneous or subcutaneous masses because it avoids surface contamination |

| Lymph nodes | ||

| Internal organs | Best method for minimally invasive sampling of internal organs or masses | |

| Fluid collection | ||

| Impression smear | Exudative cutaneous lesions | Most useful for identification of infectious organisms |

| May yield only surface cells and contamination (problem with ulcerated tumors) | ||

| Preparation of cytology samples from biopsy specimens | With biopsy specimens, it is imperative to blot excess blood from sample | |

| Impression smears of biopsy specimens must be made before exposure of biopsy sample to formalin | ||

| Scraping | Used with flat cutaneous lesions that are not amenable to fine-needle biopsy | With dry cutaneous lesions (e.g., ringworm), it is important to scrape sufficiently to obtain some blood or serum to help cells stick to slide |

| Preparation of cytology samples from poorly exfoliative biopsy specimens | ||

| Swab | Generally used only when anatomic location not amenable to collection by other means | |

| Vaginal smears | ||

| Fistulous tracts | With fistulous tracts, most useful in classifying type of inflammatory response and identifying infectious organisms |

Fine-Needle Biopsy

Fine-needle biopsy (FNB) can be performed using a standard syringe and needle with or without aspiration (as described later). This is the best overall method for sampling any cutaneous mass or proliferative lesion.1 FNB allows collection of cells from deep within the lesion, avoiding surface contamination with inflammatory cells and organisms that often plague impression smears, swabs, or scrapings. Surface cells are often poorly preserved and may show artifacts related to cellular aging and exposure to secondary inflammation responses, especially with ulcerated masses. These changes can make evaluation of the significance of cellular atypia more difficult. A classic example of this is masses of the urinary bladder. Samples collected by traumatic catheterization often contain cells that show significant degeneration and artifact from aging and prolonged exposure to urine (Figure 1-1). Conversely, samples collected via FNB from deep within the lesion are typically well preserved and easier to evaluate (see Figure 1-1, A). FNB is also the only practical technique for sampling of subcutaneous or internal organs or masses.

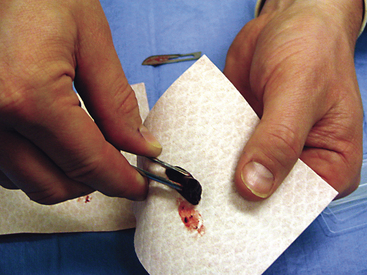

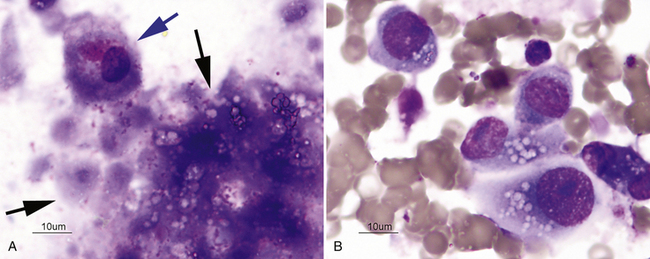

Figure 1-1 Photomicrograph of samples collected from transitional cell carcinoma.

A, Sample collected by fine-needle biopsy of the mass. The cells are well preserved allowing for examination of nuclear and cytoplasmic detail. B, Sample collected by traumatic catheterization. These samples typically collect superficial cells that show marked changes resulting from cellular aging and exposure to urine. Nuclear degeneration is noted as a homogenous light pink-purple color as well as fragmentation with numerous clear spaces evident (arrows). (Courtesy Oklahoma State University Teaching Files)

Selection of Syringe and Needle

The size of syringe used is influenced by the consistency of the tissue being aspirated. Softer tissues such as lymph nodes often can be aspirated with a 3-mL syringe. Firm tissues such as fibromas and squamous-cell carcinomas require a larger syringe to maintain adequate negative pressure (suction) for collection of a sufficient number of cells. A 12-mL syringe is a good choice if the texture of the tissue is unknown. The size of the syringe is not as critical when the samples are collected using the nonaspiration technique.

Aspiration Procedure

With the standard aspiration method of FNB, the mass is stabilized with one hand while the needle, with syringe attached, is introduced into the center of the mass (Figure 1-2). Strong negative pressure is applied by withdrawing the plunger to about three fourths the volume of the syringe (Figure 1-3). If the mass is sufficiently large and the patient sufficiently restrained, negative pressure can be maintained while the needle is moved back and forth repeatedly, passing through about two thirds of the diameter of the mass. With large masses, the needle can be redirected to several areas within the mass to increase the amount of tissue sampled. Alternatively, several different areas of the mass can be sampled with separate collection attempts. Care should be taken to not allow the needle to exit the mass while negative pressure is being applied because this can result in either aspiration of the sample into the barrel of the syringe (where it may not be retrievable) or contamination of the sample with tissue surrounding the mass.

Figure 1-2 Aspiration technique of fine-needle biopsy.

The mass is stabilized with one hand while the needle is introduced into the center of the mass. The hand holding the syringe is used to pull back on the plunger, creating negative pressure. (Courtesy Oklahoma State University teaching files.)

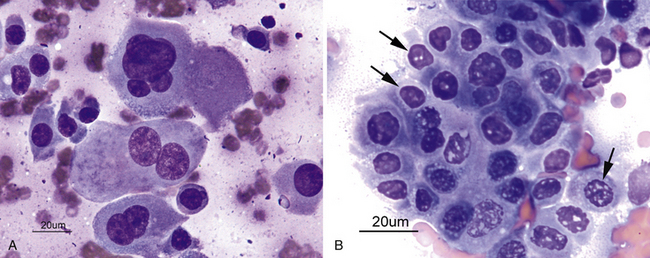

Figure 1-3 Fine-needle aspiration from a solid mass.

After the needle is within the mass (A), negative pressure is placed on the syringe by rapidly withdrawing the plunger (B), usually one half to three fourths the volume of the syringe barrel. The needle is redirected several times while negative pressure is maintained, if this can be accomplished without the needle’s point leaving the mass. Before the needle is removed from the mass, the plunger is released, relieving negative pressure on the syringe (C).

Nonaspiration Procedure (Capillary Technique, Stab Technique)

Many people prefer to collect FNB without the application of negative pressure, and this technique can yield samples of equal or better quality than those obtained with the standard aspiration technique.4–6 The nonaspiration technique works well for most masses, especially those that are highly vascular.1 This technique is similar to the standard FNB aspiration technique, except no negative pressure is applied during collection. The procedure is performed using a small-gauge needle on a 5- to 12-mL syringe. The barrel of the syringe is filled with air prior to the collection attempt to allow rapid expulsion of material onto a glass slide. The syringe is grasped at or near the needle hub with the thumb and forefinger (much like holding a dart) to allow for maximal control (Figure 1-4). The mass to be aspirated is stabilized with a free hand, and the needle is inserted into the mass. The needle is rapidly moved back and forth in a stabbing motion in an attempt to stay along the same tract, similar to the action of a sewing machine. This allows cells to be collected by cutting and tissue pressure. Care must be taken to keep the needle tip within the mass to prevent contamination with surrounding tissue. The needle is then withdrawn and the material in the needle is rapidly expelled onto a clean glass slide, and a smear is made using one of the techniques listed later in this chapter (see “Preparation of Slides”). Having the syringe prefilled with air allows the sample to be expelled onto a slide more quickly, thereby helping to avoid desiccation (drying out) of the collected cells and coagulation of the sample.6

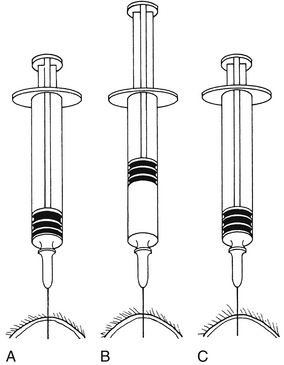

Figure 1-4 Nonaspiration technique of fine-needle biopsy.

The syringe is held at or near the needle hub with the thumb and forefinger. Note that the syringe is prefilled with air. The free hand is used to stabilize the mass. This technique allows greater control over movement of the needle. (Courtesy Oklahoma State University teaching files.)

Some perform the nonaspiration technique with a needle only with no attached syringe. This may allow for even greater control of the placement and movement of the needle, although the syringe must then be attached after sample collection to expel the material from the needle. Another variation which has been recommended for ultrasound-guided collection is to have an intravenous fluid extension set placed in between the needle and the syringe.6 This allows freedom of movement of the needle with one hand during the collection procedure. The syringe can be hung over the shoulder during collection, and then the other hand can be used to quickly expel the material onto the slide.

Collection Tips

Make and Submit Multiple Slides

There are many possible reasons for any one slide being nondiagnostic. The slide may not have any diagnostic cells because the needle missed the lesion during collection (geographic miss) (Figure 1-5) or may have been in a nonrepresentative portion of the lesion (e.g., an area of inflammation or necrosis within a neoplasm (Figure 1-6). In addition, some lesions simply do not exfoliate cells well. Even if adequate cells were collected, many times, the cells do not spread out well and the slides are too thick to be evaluated (especially common in the case of lymph node aspirates), or all of the cells are ruptured during smear preparation (Figure 1-7). Even in the hands of clinicians who are highly experienced in sample collection, it is not unusual to evaluate multiple slides from a single lesion and have all but one of the slides be nondiagnostic for one reason or another.

Figure 1-5 Geographic miss.

Sometimes, the needle is not in the area containing representative tissue of the lesion during sample collection. This is common in obese animals where the lesion may be surrounded by abundant subcutaneous fat. (Courtesy Oklahoma State University teaching files.)

Figure 1-6 Samples collected from a prostatic carcinoma with areas of necrosis.

A, Most slides were from aspirates of necrotic areas and contain predominantly necrotic cellular debris (black arrows). A single partially intact cell is present (blue arrow). These slides would be nondiagnostic. B, One of the aspiration attempts sampled a nonnecrotic area and the resulting slides contained numerous intact cells allowing a diagnosis to be made. This demonstrates the importance of sampling multiple sites of a mass. (Courtesy Oklahoma State University teaching files.)

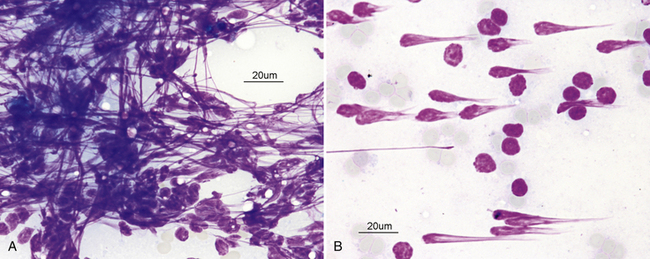

Figure 1-7 Images from an aspirate of a reactive lymph node.

This sample was nondiagnostic because all of the cells have been ruptured due to excessive downward pressure being applied during sample preparation. A, The linear streaks of material represent nuclear chromatin of ruptured cells. B, Ruptured cells often appear to have “comet tails” all going the same direction. (Courtesy Oklahoma State University teaching files.)

If multiple masses are sampled, always a new needle and syringe should be used with each mass. If this is not done, slides from one mass may be contaminated with cells left in the needle from previous collection attempts. Each slide should be clearly labeled as to the anatomic site sampled.

Impression Smears

Impression smears can be made from ulcerated or exudative superficial lesions (Figure 1-8) or tissue samples collected at surgery or necropsy (Figure 1-9). Impression smears from superficial lesions often yield only inflammatory cells even if the inflammation is a secondary process; neoplastic cells may not exfoliate in exudates or impression smears of ulcerated masses. If possible, FNB of tissue under the ulcerated or exudative area should be collected in addition to the impression smears. Inserting the needle at a nonulcerated area will help reduce contamination during collection. Impression smears of exudates or ulcers are most beneficial for determining if bacterial or fungal organisms are present. Keep in mind that bacteria may reflect only a secondary bacterial infection.

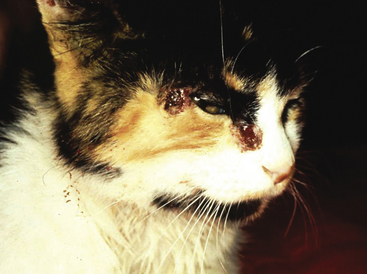

Figure 1-8 Ulcerative, exudative lesions on the face of a cat.

This lesion is well suited for impression smears. Slides from these lesions revealed inflammatory cells and many Sporothrix organisms. (Courtesy Oklahoma State University teaching files.)

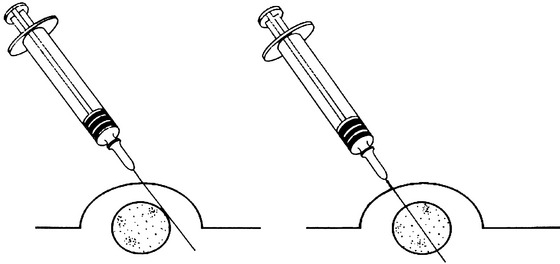

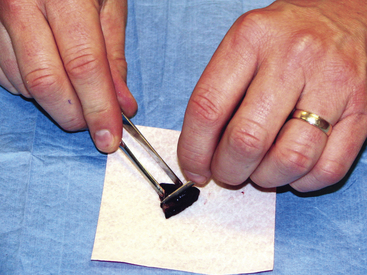

Figure 1-9 Impression smear of tissue removed at surgery.

The tissue is trimmed so that a fresh surface is created for making the impression smear. If normal tissue surrounding a mass has been excised, it is important to be sure that the tissue is cut through the area of interest. (Courtesy Oklahoma State University teaching files.)

To collect impression smears from tissues collected during surgery or necropsy, the tissue should first be cut so that a fresh surface for imprinting is created (see Figure 1-9). Next, the excess blood and tissue fluid should be removed from the surface of the lesion being imprinted by blotting with a clean absorbent material (Figure 1-10). Excessive blood and tissue fluids inhibit tissue cells from adhering to the glass slide, producing a poorly cellular preparation. Also, excessive fluid inhibits cells from spreading and assuming the size and shape they usually have in air-dried smears. After excess blood and tissue fluids have been blotted from the surface of the lesion, the surface of the lesion is touched (pressed) against the middle of a clean glass microscope slide and lifted directly up (Figure 1-11). This should be repeated several times so that several tissue imprints are present on the slide. If the excess blood has been adequately removed, the tissue will stick somewhat to the slide and will appear to peel off the slide, if removed slowly. Properly made slides will have slightly opaque areas at the areas of the impressions but should not have excessively thick areas of blood (Figure 1-12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree