CHAPTER 42 Rhythm Disturbances

Recognition and Therapy

Arrhythmias are commonly associated with both primary cardiac and extracardiac disease in cats.1,2 Arrhythmias are associated most frequently with primary myocardial disease, by far the most common form of adult-onset feline heart disease, but also may complicate severe congenital cardiac malformations. The most common extracardiac diseases complicated by arrhythmias include hyperthyroidism, systemic hypertension, and severe electrolyte derangements, such as hyperkalemia (Figure 42-1), associated most frequently with urinary tract obstruction.3,4

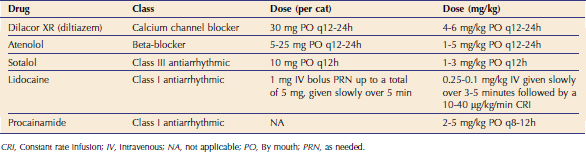

Although specific comparative studies of dogs and cats have not been reported, it is generally accepted that the frequency of clinically important arrhythmias is lower in cats.5 Nonetheless, arrhythmias are detected regularly during evaluation of cats with suspected heart disease. Despite the fact that some arrhythmias require no specific intervention, others cause important, potentially life-threatening hemodynamic compromise, making the ability to recognize and manage these rhythm disturbances imperative for optimal patient management. Goals of cardiac rhythm management should include abolishing and preventing recurrence of the rhythm derangement when possible, minimizing the hemodynamic impact of any arrhythmia that can not be terminated, and avoiding therapy-associated morbidity.6 Several antiarrhythmic drugs are used clinically in cats; however, specific studies comparing the utility of individual agents generally are lacking (Table 42-1).

IDENTIFICATION OF RHYTHM DISTURBANCES

Diagnostic ECGs by convention are recorded with the cat in right lateral recumbency. Chemical restraint rarely is necessary and may alter the diagnostic recording most notably by influencing heart rate and the proarrhythmic effects of some frequently employed agents such as ketamine and medetomidine. The improvement in the recording quality rarely outweighs the risk associated with chemical restraint and should be avoided. In patients who have respiratory embarrassment, recording the ECG in sternal recumbency or with the patient standing may provide a diagnostic recording while minimizing patient stress. When a rhythm disturbance is persistent, it may be characterized adequately with a short recording. With paroxysmal arrhythmias, longer duration recordings are required and 24-hour ambulatory (Holter) monitoring may be required to fully describe the arrhythmia. Optimal determination of response to antiarrhythmic drugs and characterization of arrhythmias ideally is accomplished with serial Holter examinations. Unfortunately, this is an underutilized technique in cats. Excellent review papers describe the technique for recording resting ECGs and Holter monitoring in cats.7–9

SINUS RHYTHM AND SINUS TACHYCARDIA

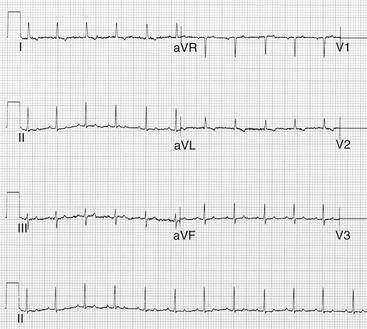

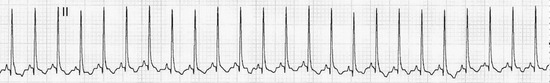

In normal healthy cats, normal sinus rhythm (NSR) is the most common underlying cardiac rhythm. NSR is defined electrocardiographically as having regularly spaced (<10 per cent P-P variation) P waves, and for every P wave there is an associated QRS complex followed by a T wave. The heart rate in cats with NSR typically is between 140 and 200 beats per minute (bpm) (Figure 42-2). Once these same morphological criteria are met, but the rate exceeds 200 bpm, a rhythm diagnosis of sinus tachycardia (arguably a normal rhythm in cats) is more appropriate (Figure 42-3).

SINUS BRADYCARDIA AND SINUS ARRHYTHMIA

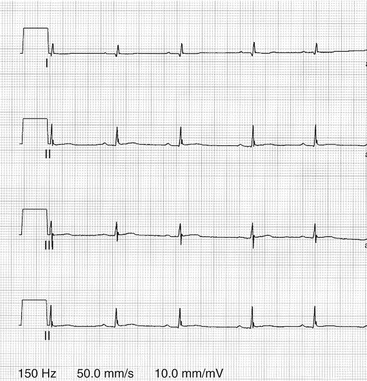

Heart rates less than 140 bpm in which the previously described P-QRS-T relationships are maintained is consistent with a diagnosis of sinus bradycardia (Figure 42-4). Sinus arrhythmia is an abnormal rhythm in cats. It is defined electrocardiographically by a gradual variation in P-P intervals that exceeds 10 per cent, which is often associated with respiration. The P-QRS-T relationships for sinus bradycardia are the same as described in the previous section. This rhythm abnormality is associated most commonly with disease that causes substantial increases in vagal tone, including intracranial disease, elevated intraocular pressure, and important primary respiratory diseases (Figure 42-5).

THERAPY

Sinus tachycardia should be viewed as an indicator of high sympathetic tone typically requiring no directed therapy. When associated with primary cardiac disease and heart failure, optimizing cardiac output and eliminating congestion usually are sufficient interventions. Sinus arrhythmia, and to a lesser extent sinus bradycardia, are caused most commonly by high vagal tone, the cause of which needs to be identified and eliminated if possible. Medications that are administered chronically to elevate heart rate, including the methylxanthine bronchodilators and propantheline, frequently are associated with unacceptable adverse side effects and are not used routinely.10

SUPRAVENTRICULAR TACHYARRHYTHMIAS

ATRIAL PREMATURE OR SUPRAVENTRICULAR PREMATURE COMPLEXES

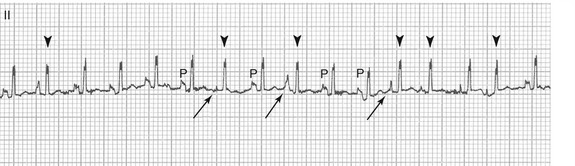

Atrial premature complexes are associated most commonly with atrial enlargement secondary to primary cardiac disease but may be caused by a variety of extracardiac diseases, including hyperthyroidism. Atrial premature complexes occur by definition earlier than the next anticipated sinus impulse, have demonstrable atrial activity (P), and the QRS complex is morphologically similar if not identical to that associated with a normal sinus origin impulse (Figure 42-6). Frequently, the more generic term of supraventricular premature complexes is used to encompass an atrial, nodal, or junctional origin. Although isolated commonly, atrial premature complexes also can occur in couplets and triplets. If four or more atrial premature complexes occur sequentially, they are classified as paroxysmal atrial or supraventricular tachycardia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree