Chapter 8 Respiratory system

Respiration is the gaseous exchange between an organism and its environment. All animals require oxygen to carry out the chemical processes that are essential for life: oxygen is needed by the cells to obtain energy from raw materials derived from food. This process involves the oxidation of glucose to yield energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (see Ch. 1). Water and carbon dioxide are produced as byproducts of this reaction. Respiration can be considered to occur in two stages:

The respiratory system consists of:

Structure and function

Nose

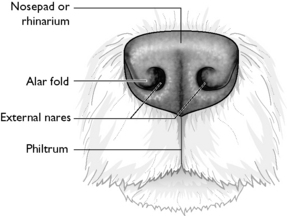

Inspired air enters the respiratory system through the nostrils or external nares leading into the nasal cavity, which is divided by a cartilaginous septum into the right and left nasal chambers. The entrance to the nasal cavity is protected by a hairless pad of epidermis consisting of a thick layer of stratified squamous epithelium, which is heavily pigmented and well supplied with mucous and sweat glands – this is known as the rhinarium and it is penetrated by the two curved nares (Fig. 8.1). The epidermis on a dog’s nose has a unique patterning that is much like a human ‘fingerprint’.

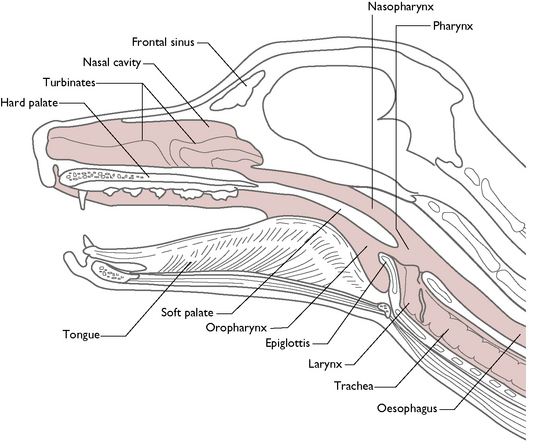

The right and left nasal chambers are filled with fine scrolls of bone called turbinates or conchae (Fig. 8.2). The chambers and the turbinates are covered by a ciliated mucous epithelium, which is well supplied with blood capillaries. The turbinates arising from the ventral part of the nasal cavity end rostrally in a small bulbous swelling visible through the nostril – the alar fold.

Fig. 8.2 Longitudinal section to illustrate the upper respiratory tract of the dog.

(With permission from Colville T, Bassett JM 2001 Clinical anatomy and physiology for veterinary technicians. Mosby, St Louis, MO, p 222.)

Towards the back of the nasal chambers, the mucous epithelium covering the turbinates has a rich supply of sensory nerve endings that are responsive to smell – this is the olfactory region. These nerve fibres pass through the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone to reach the olfactory bulbs of the forebrain (see Ch. 5). The remainder of the mucous membrane is the respiratory region.

Paranasal sinuses

A sinus is an air-filled cavity within a bone. Within the respiratory system, they are referred to as the paranasal sinuses and lie within the facial bones of the skull (Fig. 8.2). They are lined with ciliated mucous epithelium and communicate with the nasal cavity through narrow openings.

It is thought that the function of the paranasal sinuses is to lighten the weight of the skull, allowing the areas of the skull used for muscle attachment to be larger. This is evident in those species that have large, heavy skulls, such as the horse, which has numerous large paranasal sinuses. The paranasal sinuses also act as areas for heat exchange and as sites for mucus secretion.

Pharynx

From the nasal cavity, the inspired air passes into the pharynx, a region at the back of the mouth that is shared by the respiratory and digestive systems. The pharynx is divided into the dorsal nasopharynx and the ventral oropharynx by a musculomembranous partition called the soft palate (Fig. 8.2). The soft palate extends caudally from the hard palate and prevents food from entering the nasal chambers when an animal swallows (see Ch. 9). The oropharynx conducts food from the oral cavity to the oesophagus; the nasopharynx conducts inspired air from the nasal cavity to the larynx, but air can also reach the respiratory passages from the mouth, e.g. during ‘mouth breathing’.

A pair of Eustachian or auditory tubes also opens into the pharynx and connects the pharynx to each of the middle ears (see Ch. 5). The function of the Eustachian tubes is to equalise the air pressure on either side of the ear drum.

Larynx

The inspired air enters the larynx, which lies caudal to the pharynx in the space between the two halves of the mandible (Fig. 8.2). The function of the larynx is to regulate the flow of gases into the respiratory tract and to prevent anything other than gases from entering the respiratory tract.

The larynx is suspended from the skull by the hyoid apparatus (see Ch. 3), which allows it to swing backwards and forwards (Fig. 8.3). The hyoid apparatus is a hollow, box-like structure consisting of a number of cartilages connected by muscle and connective tissue. The most rostral of these cartilages, the epiglottis, is composed of elastic cartilage and is responsible for sealing off the entrance to the larynx or glottis when an animal swallows. This prevents saliva or food from entering the respiratory tract, causing the animal to choke. When the larynx returns to its resting position after swallowing the epiglottis falls forward, opening the glottis and thus allowing the passage of air to resume.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree