Chapter 16 Respiratory Disease and Pasteurellosis

Respiratory disease is common in pet rabbits and, as in other species, is caused by a number of primary and secondary etiologies. Although the anatomy of the respiratory tract is discussed in more detail in Chapter 12, it should be kept in mind that rabbits are obligate nasal breathers because of the position of the elongated epiglottis engaged over the caudal margin of the soft palate. For this reason, mouth breathing is an indication of a severe abnormality. In general, disease of the upper respiratory tract is more severe and stressful in rabbits than in other species. Respiratory disease can be classified as affecting the upper or lower respiratory tract or both.

Anatomy of the Respiratory Tract

The nasal cavities contain the conchae; these structures create the ventral, middle, dorsal, and common meatus. The ventral meatus continues to the rhinopharynx. Two blind cavities inside the conchae are commonly termed sinuses and are often reported as the conchal and maxillary sinuses. As these cavities are blind, the more correct term may be recesses. There is a single opening of each sinus into the nasal cavity. Each lung is divided into cranial, middle, and caudal lobes, with the right lung also possessing an accessory lobe. The volume of the thoracic cavity of the rabbit is small, especially in comparison with the volume of the abdominal cavity.17

Diseases of the Upper Respiratory Tract

Infectious

Numerous infectious diseases are associated with disease of the upper respiratory tract; they are due mainly to bacterial agents, but in rare cases, viral, fungal, or parasitic pathogens may be involved as well. The rabbit is a common research model for rhinitis and sinusitis. Sinusitis is established after mechanical blockage of the ostium connecting the nasal and sinus cavities, resulting in impaired mucociliary function and clearance of organisms from the sinus cavity.2 Ostial dysfunction appears to be an important requirement for the establishment of infection in laboratory models, especially for organisms not considered primary pathogens, and may have significance for naturally infected animals as well.

Otitis media is associated with respiratory disease in rabbits, as infection can spread via the eustachian tube to the tympanic bulla and middle and possibly inner ear.11,17

Bacterial Pathogens

While Pasteurella multocida is often implicated as a cause of respiratory disease, other pathogens must be considered. A recent epidemiologic study of 121 rabbits with symptoms of upper respiratory tract disease (nasal discharge and sneezing) indicated that the most common bacterial isolates (deep nasal samples) were P. multocida (54.8%), Bordetella bronchiseptica (52.2%), Pseudomonas species (27.9%), and Staphylococcus species (17.4%). Mixed infections were also seen.30

Pasteurellosis is associated with many disease processes in rabbits including rhinitis, sinusitis, conjunctivitis, nasolacrimal duct infection, otitis, tracheitis, pneumonia, and abscesses (dental, skin, other). While not identified as a pathogen in wild rabbit populations, Pasteurella is a significant pathogen in laboratory animals, leading to the development of “Pasteurella-free” animals for research use. Because of its ubiquitous nature, many pet rabbits are already infected with Pasteurella multocida. Many exhibit symptoms in response to stress, such as stress of weaning, transport, and purchase from the pet store as well as poor sanitation and ventilation and concurrent illnesses.11

Strains of Pasteurella vary in pathogenicity,27 with some being more likely to spread via the hematogenous route and causing acute septicemia, generalized disease, and death. P. multocida gains entry to the host primarily through the nares or wounds via aerosolization or direct contact with infected rabbits or fomites. Does with venereal infections may pass the organism to their young, who may remain apparently uninfected for several weeks until signs of infection develop. Infected rabbits can resist infection or become subclinical carriers, thus complicating determination of an incubation period. In experimental studies, rhinitis occurred 1 to 2 weeks after intranasal inoculation.24 After infection, the organism spreads to the sinuses, nasolacrimal duct, eustachian tube and middle ear, trachea, and lungs. Factors facilitating disease expression include exposure to ammonia through improperly cleaned enclosures, administration of corticosteroids, and the psychologic stress or stress of concurrent disease.10 Recent studies have indicated promise for the development of vaccines as an aid to management of this disease.33

B. bronchiseptica is a common inhabitant of the rabbit respiratory tract, and disease prevalence may increase with age.11 Experimental inoculation of organisms may or may not produce disease. This organism is pathogenic in guinea pigs, dogs, cats, and pigs. B. bronchiseptica is suspected to be a copathogen or predisposer to infection with P. multocida. However, Deeb has reported severe infection in the absence of P. multocida in a colony of inbred laboratory rabbits, suggesting that more pathogenic strains may exist (BJ Deeb and RF DiGiacomo, unpublished data).

Pseudomonas species infections in rabbits are common. Rabbits are used as a laboratory model for human Pseudomonas infections in multiple body systems, including the cardiovascular system.21

Staphylococcus species is commonly isolated from the nares of rabbits and is thought to be a secondary invader. Pathogenicity depends on host susceptibility and bacterial virulence. Disseminated staphylococcosis has been linked with fibrinous pneumonia or abscesses in the lung or heart.10

A number of other pathogens can produce upper respiratory disease in rabbits. Pasteurella species other than P. multocida can be cultured from rabbits but may be nonpathogenic. However, pure cultures associated with clinical disease should be treated as true pathogens. Other potential pathogens include Moraxella species, Yersinia pestis, and Escherichia coli. Mycoplasma pulmonis was isolated by Deeb in the rhinopharynx of rabbits with evidence of upper respiratory disease. Infected rabbits were housed in close proximity to rats, which may have been the source of the infection.10 S. Kelleher (personal communication) reported a case of nasal granuloma produced by Mycobacterium species.

Viral Pathogens

Viral pathogens other than myxoma virus producing primary upper respiratory disease are uncommon. Myxoma virus can produce nasal and ocular disease as well as dyspnea as a feature of the disease; it has also been associated with acute hemorrhagic pneumonia.23,25 An outbreak of a herpesvirus was reported in a commercial rabbitry in Alaska in 2008. Respiratory signs and symptoms were a prominent feature.22

Fungal Pathogens

Fungal granulomas of the sinuses have been described in pet rabbits and, as in other species, appear to require primary injury. Techniques used in rabbits to produce experimental models of fungal sinusitis include mucosal injury and blockage of the ostium.13 Simple introduction of pathogenic fungi into the nasal cavity usually does not produce disease.

Noninfectious

Trauma

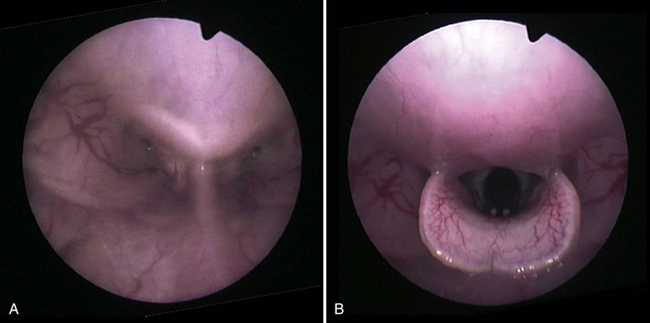

Traumatic injury to the upper respiratory tract includes blunt force trauma, predator injury, and damage to the glottis and trachea after endotracheal intubation. There are numerous reports of inflammation of the glottis and stenosis of the trachea in the laboratory literature.15,29 In one report of three cases of tracheal stenosis secondary to intubation, evidence of respiratory disease appeared within 17 to 21 days postintubation. Risk factors could not be identified.29 The author has regularly performed blind endotracheal intubation in rabbits and taught the technique to students and support staff for over 10 years. The most severe complications have been rare cases of mild respiratory stridor that did not persist beyond 24 hours postprocedure. In normal position, the epiglottis is above the soft palate in the rabbit and other obligate nasal-breathing species, preventing both mouth breathing and access to the trachea via the oral cavity. Hyperextension of the head causes the epiglottis to disengage and reposition below the soft palate, allowing access to the trachea (Fig. 16-1). Other keys to successful intubation appear to be correct tube size (2-3 mm) and gentle technique without the use of pressure during placement.

All mammalian species are susceptible to airway irritation due to chemical exposure, and mucosal damage may predispose to infection. Numerous studies have demonstrated upper airway and lung damage secondary to irritants such as tobacco and dried dung smoke.14 Other potential sources of respiratory irritants include household chemicals and ammonia from poorly cleaned enclosures.

Foreign materials in the nares, pharynx, or trachea have been reported. In one rabbit with chronic sneezing, its clinical signs ceased following removal of hay from the nares.32

Dental Disease

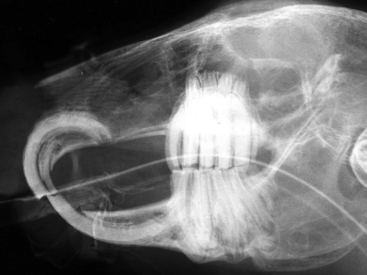

Certain expressions of dental disease can produce symptoms of respiratory disease, including epiphora and nasal discharge.6 The nasolacrimal duct in the rabbit courses close to the apex of first maxillary incisor tooth and the first maxillary cheek tooth (Fig. 16-2). Therefore abnormalities or infections of the apices and reserve crowns of these teeth can affect the natural course of the duct, resulting in epiphora. More severe disease can produce infection or abscess of the duct and subsequent purulent nasal discharge. Elongation, deformation, and infection of the roots of maxillary cheek teeth (in particular the first two cheek teeth) can affect the nasal cavity, resulting in chronic nasal discharge and sinusitis.6

Miscellaneous Conditions

An apparent congenital abnormality characterized by incomplete tracheal rings has been diagnosed in a rabbit with dyspnea and an appreciable honking noise upon inspiration. Collapsing trachea was identified upon tracheoscopy; incomplete rings were confirmed at histopathology.9

Diseases of the Lower Respiratory Tract

Infectious

Infectious agents, as described previously, also produce lower respiratory disease, with classic clinical signs and presentation of pneumonia. P. multocida and sometimes other organisms can also produce pleuritis and pericarditis. A study of 66 rabbits with pulmonary lesions isolated the following pathogenic bacteria in this order of frequency: Pasteurella species including multocida, E. coli, B. bronchiseptica, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.25

Chlamydia species have been isolated from the lungs of domestic rabbits with pneumonia. A mild interstitial pneumonia occurred when the agent was inoculated into the trachea of laboratory rabbits.10

Pneumocystis oryctolagi has been isolated from the lungs of newly weaned rabbits.12 Myxomavirus has been associated with acute hemorrhagic pneumonia.25

Neoplastic

A number of neoplasms produce metastasis to the lungs or, in the case of thymoma or thymic lymphoma, indirectly affect the lower respiratory tract. Neoplasms producing metastasis to the lungs include uterine adenocarcinoma, osteosarcoma, lymphoma, and mammary carcinoma.36 Primary carcinoma of the lungs of a 7-year-old rabbit has also been reported.19

Thymoma is a primary tumor of lymphoid or epithelial origin and is increasingly reported in the literature.26 Common clinical features include decreased activity, increased respiratory rate and effort, and bilateral exophthalmos, which can be intermittent and often increases in severity over time. Exophthalmos is thought to occur secondary to vascular compression and reduction of vascular return to the heart caused by the growing mass.26

Diseases Producing Secondary Respiratory Symptoms

Cardiovascular disease can produce signs that suggest respiratory disease, including increased respiratory rate and effort. As the life span of pet rabbits increases, it can be expected that the incidence of cardiac disease will increase as well.17 Cardiomyopathy, endocardiosis, and congestive heart failure have been reported in rabbits.28

Diaphragmatic herniation with entrapment of the stomach, parts of the intestinal tract, and kidney has been identified, as well as pneumothorax secondary to trauma.7

Diagnosis and Differentiation

Physical Examination

Symptoms of respiratory disease can be similar to those noted in other traditional pet species; they include nasal and/or ocular discharge and increased respiratory effort and rate, often worsening with exertion. Ocular and nasal discharge frequently produces wet or matted fur beneath the eyes and nares. Rabbits with ocular or nasal discharge often attempt to remove the material with the forefeet, resulting in an accumulation of debris in the fur of the medial aspect of the feet.17 In addition, rabbits with tracheitis will often cough when the trachea is gently palpated. Because rabbits are obligate nasal breathers, diseases producing nasal discharge or other occlusion of the nares can lead to severe respiratory distress.17 Other nonspecific symptoms that should arouse suspicion of respiratory disease include weight loss, decreased appetite, lethargy, and exercise intolerance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree