22 Regurgitation

Regurgitation is the passive expulsion of oesophageal or gastric contents from the oral cavity, and is most commonly the result of oesophageal disease. Regurgitation is the most common sign of, but not pathognomonic for, oesophageal disease, and other differential diagnoses, in particular pharyngeal disorders, must be considered. There are a large number of possible causes of regurgitation; some of the more common are listed in Box 22.1. In the author’s experience, megaoesophagus and oesophageal foreign bodies are the most common reasons for regurgitation in emergency patients.

BOX 22.1 Causes of regurgitation related to the oesophagus

Idiopathic (primary) megaoesophagus, congenital or acquired

Clinical Tip

Table 22.1 Comparison of regurgitation and vomiting

| Regurgitation | Vomiting |

|---|---|

| No prodromal signs; signs associated with pain may mimic nausea | Prodromal signs of nausea (e.g. hypersalivation, restlessness) |

| Passive (no abdominal contractions); postural changes associated with pain possible (e.g. stretching neck) | Active with abdominal contractions |

| No consistent relationship with feeding | No consistent relationship with feeding |

| Undigested (or digested) food, or liquid; undigested food often tubular in shape | Digested food |

| No bile but may contain frothy saliva | Bile may be present |

Approach to Regurgitation

History

It is important to question the owner carefully for a good description of the animal’s behaviour in order to differentiate regurgitation from vomiting and even retching or gagging (see Table 22.1). Other signs consistent with oesophageal disease may also be present and include hypersalivation, pain on eating and dysphagia. A history of coughing or respiratory abnormalities may suggest aspiration pneumonia.

Emergency database

The emergency database may well be unremarkable in a number of animals with regurgitation. Manual packed cell volume and serum total solids may be consistent with dehydration in some cases. Peripheral blood smear examination may demonstrate leucocytosis consistent with inflammatory disease, including moderate to severe oesophagitis, and neutrophils may show toxic changes and band forms with aspiration pneumonia (see Ch. 3). Megaoesophagus is occasionally identified in animals with hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease, see Ch. 34) and consistent abnormalities may be identified (hyponatraemia, hyperkalaemia, hypoglycaemia, azotaemia; lack of stress leucogram).

Diagnostic imaging

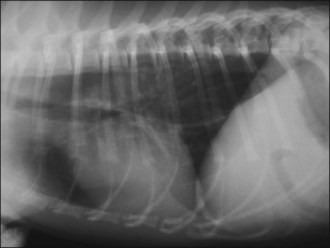

Plain thoracic radiographs (typically right lateral and dorsoventral (or left lateral) views) are useful in animals with regurgitation and may help to identify megaoesophagus, radiopaque oesophageal foreign bodies, aspiration pneumonia and mediastinal masses (Figures 22.1–22.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree