M. Eilidh Wilson, N. Edward Robinson

Recurrent Airway Obstruction and Inflammatory Airway Disease

Recurrent airway obstruction (RAO) and inflammatory airway disease (IAD) are common inflammatory obstructive diseases of the equine tracheobronchial system. Recurrent airway obstruction, which is the most severe of the two conditions, is defined by periods of reversible airway obstruction that are induced by exposure to organic dusts. The relationship between RAO and the less severe IAD is being investigated, and the data suggest that some IAD-affected horses are in the early stages of RAO. However, many IAD-affected horses may never go on to develop the typical signs of RAO. Inflammatory airway disease in racehorses may be a different syndrome from that observed in older sport horses.

Recurrent Airway Obstruction

Horses with RAO are hypersensitive to dust in hay. Susceptibility is hereditary, yet the disease only manifests in mature adult horses, generally in those older than 5 years, despite horses being exposed to hay dust from a young age. The disease is characterized by two clinical phases: active disease and remission. Active disease develops after inhalation of hay dust, which acts as an immunologic trigger inciting a pulmonary response characterized by bronchoconstriction, mucus production, and bronchoalveolar neutrophilic inflammation. The severity of airway obstruction, inflammation, and consequent pulmonary dysfunction can vary tremendously, but it is a characteristic feature of the disease that inflammation and bronchoconstriction gradually resolve when hay or other inciting sources of dust are removed. During those times, horses are said to be in remission. Horses maintain lifelong susceptibility, and any reexposure to hay dust reinitiates active disease; horses thus tend to vacillate between active and remission states, and commonly are presented with chronic history of waxing and waning respiratory disease. Common owner complaints typically include coughing, nonpurulent nasal discharge, reduced performance, and difficulty breathing at rest.

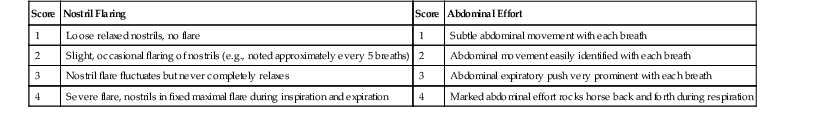

Clinical examination findings depend on the severity of disease at presentation, but during active disease, expiratory wheezes and early inspiratory crackles may be auscultated when the horse is at rest (or elicited with use of a rebreathing bag), and gurgling or rattling produced by mucus movement may be auscultated in the distal cervical portion of the trachea. A hallmark of active disease is an abnormal breathing pattern at rest; the rate and effort are increased (the abdominal effort is particularly visible), and the rhythm becomes more regular. A clinical scoring system can be used to classify disease severity (Table 59-1). Pulmonary function tests performed during active disease detect increased resistance, increased maximal change in pleural pressure, and reduced dynamic compliance, but these measurements are generally only performed in a research setting. Affected horses are otherwise healthy with no evidence of systemic disease.

Moderate to severe RAO is relatively easy to diagnose on the basis of clinical signs, signalment, and a history of recurrent bouts of coughing, increased respiratory effort, and exposure to hay or other inciting dust. Although not always required, a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) can be performed (see Chapter 48), and cytologic findings of nondegenerative neutrophilic inflammation (>20% neutrophils) support a diagnosis of RAO. Very high neutrophil percentages (e.g., 50% to 80%) may be observed in some horses.

An RAO-susceptible horse in remission has normal findings on physical examination, and normal clinical score, BAL cytology, and standard pulmonary function test results. If the horse has been in remission for some time, it may be indistinguishable from a healthy horse. However, even in remission, horses can have subclinical inflammation and bronchoconstriction that can affect performance in upper level athletic horses.

Treatment

Successful treatment of the disease can be challenging because effective therapy fundamentally requires permanent management modifications to reduce exposure to hay dust and improve air quality (see Chapter 56). Optimally, a susceptible horse would be maintained on 24-hour year-round pasture, with strict avoidance of hay, but this is rarely achievable. Alternatively, indoor air quality can be significantly improved by using low-dust bedding alternatives (e.g., wood shavings or paper bedding) or changes in routine (removing the horse from the stall during stall cleaning and when aisles are being swept). Adjacent stalls should be similarly treated because nearby hay or straw can still contribute to dust content of the airspace. For severely affected horses, hay should be completely eliminated from the diet and from the immediate environment and replaced with pasture and a complete pelleted feed; however, owners may be resistant to this change because of increased cost and labor. Alternatively, hay can be soaked, but this can be laborious, messy, difficult in winter, and ineffective if the interior of the hay flake is not adequately soaked. Steam processing hay appears to be a practical and effective method to reduce the antigenicity of hay, but the expense of hay steamers may limit their use. Feeding bagged silage is an effective method of controlling exacerbations of RAO in cool climates. In warmer climates, silage may deteriorate rapidly after the bag is opened.

Although environmental changes should be the focus of any treatment regime, administration of corticosteroids and bronchodilators may be required when environmental changes are insufficient (Table 59-2). Corticosteroids reduce inflammation and consequently improve pulmonary function, whereas bronchodilators largely provide symptomatic relief. The choice of corticosteroid and bronchodilator depends on the severity of disease, expense of drug, and level of time commitment that the owner is willing to invest. Dexamethasone is the corticosteroid of choice for treatment of severe RAO, and improvements in pulmonary function can be observed within 2 hours when high doses are administered. The intravenous formulation of dexamethasone can also be delivered orally, but because food in the gastrointestinal tract can reduce bioavailability, corticosteroids (dexamethasone and prednisolone) are best orally administered to fasted horses.

TABLE 59-2

Treatments Used in Horses With Recurrent Airway Obstruction or Inflammatory Airway Disease*

| Administration Route | Onset of Action | Duration of Activity | Frequency | Dosage | ||

| Bronchodilators | ||||||

| Albuterol | β2 agonist† | Inhalation | Rapid (5 min) | Short (1-3 hr) | q 3 hr | 360-720 µg |

| Clenbuterol (Ventipulman) | β2 agonist† | PO | Long (6-8 hr) | q 12 hr | 0.8-3.2 µg/kg | |

| Ipratropium bromide | Anticholinergic | Inhalation | Fast (15-30 min) | Moderate (4-6 hr) | q 6 hr | 360 µg |

| Buscopan (N-butylscopolammonium bromide) | Anticholinergic | IV | Rapid (2 min) | Very short (30 min) | Single dose | 0.3 mg/kg |

| Atropine | Anticholinergic | IV | Fast (15 min) | Short (1-2 hr) | Single dose | 0.02 mg/kg |

| Corticosteroids | ||||||

| Fluticasone propionate | Inhalation | q 12 hr | 2000-6000 µg | |||

| Beclomethasone | Inhalation | q 12 hr | 1500-3000 µg | |||

| Dexamethasone | IV/IM | q 24 hr | 0.05-0.1 mg/kg | |||

| PO (60% bioavailability) | q 24 hr | 0.05-0.16 mg/kg | ||||

| Prednisolone | PO | q 24 hr | 2 mg/kg | |||

| Antimicrobials for Inflammatory Airway Disease | ||||||

| Ceftiofur | IM | q 24 hr | 2.2-4.4 mg/kg | |||

| Oxytetracycline | IV | q 12-24 hr | 5-10 mg/kg | |||

| Doxycycline | PO | q 12 hr | 10 mg/kg | |||

| Trimethoprim-sulfonamide‡ | PO | q 12 hr | 15-30 mg/kg | |||

| Procaine penicillin G | IM | q 12-24 hr | 22,000 IU/kg | |||

| Sodium/potassium penicillin | IV | q 4-6 hr | 22,000-44,000 IU/kg | |||

| Miscellaneous Treatments for Inflammatory Airway Disease | ||||||

| Disodium cromoglicate (Intal, NasalCrom) | Nebulization | q 12-24 hr | 0.2-0.5 mg/kg | |||

| Recombinant human interferon-α | PO | q 24 hr | 90 U | |||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree