Chapter 30 PROSTATITIS

The primary disorders affecting the prostate gland are benign hyperplasia with variable degrees of cyst formation, infection, abscessation, paraprostatic cysts, and neoplasia. Of these, bacterial prostatitis and benign prostatic hyperplasia are the most common prostatic disorders affecting the dog (Krawiec and Heflin, 1992) and the most likely disorders to affect fertility. Prostatic cysts and neoplasia are not commonly associated with reproductive dysfunction and are not discussed.

MECHANISMS OF PROSTATE-INDUCED INFERTILITY

Spread of infection to the epididymis and testis is the most worrisome problem related to infertility. An infected prostate gland may serve as a source of infection to the epididymis and testis via the vas deferens or, less commonly, through hematogenous spread. Orchiepididymitis and immune-mediated orchitis can result. Bacterial prostatitis can affect semen without histologic abnormalities in the testis, presumably as a result of changes in seminal fluid. In one study of induced prostatic infection using Escherichia coli, two of six dogs had a marked decrease in the percentage of normal sperm (from >90% normal to <65%) and a marked increase in primary and secondary morphologic abnormalities despite histologically normal testes (Barsanti et al, 1986). Chronic E. coli prostatitis had no apparent effect on sperm concentration or motility; however, a deleterious effect on these parameters requires a large concentration of bacteria (>106/ml).

Benign prostatic hyperplasia is usually an insignificant finding in the dog but on occasion has been associated with infertility. The underlying cause of hyperplasia-induced infertility is not known, although hemorrhage into the ejaculate has been proposed as a possible reason. Blood is spermicidal and may cause infertility if consistently present in the ejaculate. The effect of benign prostatic hyperplasia on semen volume (see page 940) does not seem to be deleterious to fertility. Unlike in humans, benign prostatic hyperplasia does not usually cause occlusion of the urethral lumen in dogs.

ACUTE BACTERIAL PROSTATITIS

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The distal urethra of the dog has a normal microflora composed primarily of gram-positive bacteria (Barsanti and Finco, 1983). The prostate gland is the genital organ closest to the microflora of the distal urethra. Normally, the prostatic urethra and prostate gland are sterile. Migration of bacteria up the urethra to the prostate gland and bladder is prevented by various defense mechanisms, including the flushing action from unobstructed flow of urine and prostatic secretions, urethral peristalsis, the urethral high-pressure zone, surface characteristics of the urethral mucosa that trap bacteria, local IgA production, and prostatic antibacterial factor (Klausner and Osborne, 1983; Dorfman and Barsanti, 1995). Prostatic antibacterial factor is a low molecular weight zinc compound that inhibits bacterial growth, especially gram-negative enteric organisms. Alterations in any of these defense mechanisms may allow bacteria to ascend into, adhere to, and colonize the prostate gland.

Disorders that increase bacterial numbers in the prostatic urethra (e.g., bacterial cystitis, urethral calculi, neoplasia), compromise local immunity, or alter the architecture of the prostate (e.g., squamous metaplasia, hyperplasia) increase the risk of an infection of the prostate gland developing. Prostate growth is androgen dependent. The principal androgen regulating prostatic growth is 5α-dihydrotestosterone, which is formed from testosterone by the enzyme 5α-reductase (Rhodes, 1996). Estrogens induce squamous metaplasia and duct obstruction and reduce the conversion efficiency of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone by prostatic cells. Both estrogens and androgens must be present for significant hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the prostate gland to occur (Cochran et al, 1981; Winter and Liehr, 1996).

The bacteria that cause infection of the prostate are generally similar to those that cause urinary tract infection. It is likely that most cases of bacterial prostatitis occur secondary to infections with urinary tract bacterial pathogens that enter the prostate via the urinary tract. However, about one third of dogs in which prostatic infection is demonstrated do not have concurrent or historical urinary tract infections (Ling, 1995). E. coli is the most common cause of bacterial prostatitis in dogs. This infection is followed, in order of incidence, by infections with coagulase-positive staphylococci, streptococci, Klebsiella sp., Proteus mirabilis, Enterobacter sp., and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Ling, 1995). A single organism is identified in approximately 70% of dogs with acute prostatitis (Dorfman and Barsanti, 1995). Mycoplasma sp. are identified in approximately 15% of dogs with bacterial prostatitis, compared with a prevalence of approximately 3% in dogs with urinary tract infections (Ling, 1995). Brucella canis, although an uncommon cause, can also give rise to acute and chronic prostatitis.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs of acute prostatitis usually include lethargy, inappetence, urethral/preputial discharge (blood, pus), and abdominal pain. Additional clinical signs may develop, depending on the degree of involvement of the prostate gland, the presence or absence of abscessation, and involvement of the bladder, epididymis, and testis (Table 30-1). In one study, 26% of dogs diagnosed with prostatitis showed signs of urinary tract disease, 37% showed gastrointestinal signs, and 48% showed signs of systemic illness (Krawiec and Hefland, 1992).

TABLE 30-1 POTENTIAL CLINICAL SIGNS ASSOCIATED WITH ACUTE BACTERIAL PROSTATITIS

Physical examination usually reveals fever and nonspecific or caudal abdominal pain. These dogs frequently have a painful prostate on rectal palpation. The prostate may be normal in size, shape, and symmetry or may be irregular in size and surface conformation. The median raphae may not be readily identifiable, and fluctuant areas may be present, especially if abscessation is present. In older dogs, benign prostatic hyperplasia and associated prostatic enlargement may be present in addition to prostatitis. If ascension to the testis and epididymis has occurred, findings suggestive of acute orchiepididymitis may also be present (see page 971).

Diagnostic Evaluation

A tentative diagnosis of acute prostatitis can usually be made from the history and physical findings. Results of a complete blood count (CBC) may reveal leukocytosis and neutrophilia with a variable shift toward immaturity and toxic changes. These alterations are exaggerated with prostatic abscessation (Barsanti and Finco, 1984). Measurement of serum concentrations of proteins of prostatic origin (i.e., acid phosphatase, prostate specific antigen, canine prostate specific esterase) is not helpful in differentiating dogs with bacterial prostatitis from healthy dogs or dogs with other prostate disorders (Bell et al, 1995). The results of a urinalysis may reveal hematuria, pyuria, and bacteriuria, although findings can be normal. Urine should be cultured if obtained by antepubic cystocentesis. The prostate is often assumed to be infected with the same organisms grown on urine culture (Black et al, 1998). However, mixed infections have been documented, in which the organism and its antibiotic sensitivity pattern differ between the bladder/urethra and the prostate (Ling et al, 1990). In these dogs, antibiotic therapy aimed at the organisms in the bladder may not control the prostate infection. For this reason, culture of prostatic fluid or tissue is recommended in dogs suspected of having prostatitis (see below).

Semen may be difficult to obtain and is usually not evaluated unless culture of the ejaculate is used to confirm bacterial prostatitis. The most common abnormalities identified on semen evaluation in acute bacterial prostatitis are neutrophils with variable degrees of toxicity, phagocytized bacteria, decreased sperm motility, and an increase in the number of spermatozoa with primary and secondary morphologic defects.

Radiographic evaluation of a dog suspected of having acute prostatitis is seldom informative. Normally, the prostate gland is located at the rim of the pelvis. However, the position of the prostate varies according to the degree of bladder distention. Radiographically, the normal prostate gland has a uniform soft tissue density and uniform, distinct margins. Radiographic alterations associated with acute prostatitis, if any, include an increase in size, mineralization, and indistinct margins (Feeney et al, 1987a). The presence of gas in the prostate gland may be iatrogenic from prior urinary bladder catheterization or may be indicative of an abscess. Reflux of contrast material into the stroma of the prostate gland and alterations in urethral diameter may be observed with positive-contrast urethrography, but these are nonspecific features of prostatic disease.

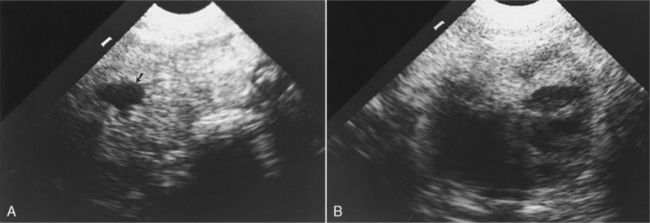

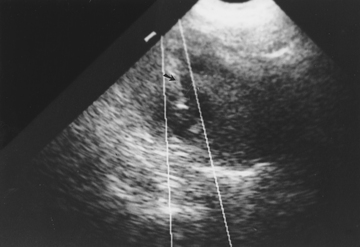

Ultrasonography provides the safest and most informative screening test of the prostate (see page 946). Ultrasonographic findings in dogs with acute prostatitis include normal to enlarged prostate gland size with symmetric or asymmetric shape and smooth or irregular borders. The prostatic parenchyma has a heterogeneous pattern of mixed echogenicity characterized by focal or multifocal areas of poorly marginated hypoechogenicity and focal irregular hyperechoic foci (Mattoon and Nyland, 1995). Hypoechoic to anechoic, fluid-filled parenchymal cavities may also be identified (Fig. 30-1) (Feeney et al, 1987b). The latter may be abscesses or cysts. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (see below) of hypoechoic or anechoic areas provides prostatic fluid for culture and cytologic evaluation. Prostatic parenchyma can also be biopsied under ultrasound guidance.

PROSTATE SAMPLING TECHNIQUES.

Regardless of the technique used, evaluation of results must take into account the number and type of organisms grown, their quantitative numbers, and the presence or absence of neutrophils and squamous cells containing bacteria in the sample (Barsanti et al, 1980). Contamination of the sample should be suspected with the following results: low numbers of neutrophils, growth of only gram-positive organisms or multiple organisms, or the presence of squamous cells containing bacteria (urethral origin). Infection should be suspected if large numbers of organisms (>105/ml) are grown, especially if they are gram-negative organisms or organisms grown in pure culture, or if large numbers of neutrophils are present (Ling, 1990).

SEMEN CULTURE.

Culture of the third fraction of the ejaculate is an effective method of identifying organisms, especially when specimens from the urethra and bladder are obtained at the same time and are cultured simultaneously (Ling et al, 1983). Culture of the second fraction of the ejaculate can also be performed if concurrent orchitis/epididymitis is suspected or fractionation of the semen is difficult. Prostatic fluid is ejaculated into all three fractions of the semen (Johnston et al, 2001). Unfortunately, an ejaculate may be difficult to obtain from a dog with painful acute prostatitis. In addition, normal dogs have occasional white and red blood cells, and positive bacterial cultures of prostatic fluid obtained by ejaculation have been reported in 30% of healthy dogs (see Table 27-4, page 942) (Bjurstrom and Linde-Forsberg, 1992). Interpretation of culture results of an ejaculate may be made with confidence only if the urine, the urethral swab, and the ejaculate specimens are cultured quantitatively and the results compared. For a diagnosis of prostatitis, the number of bacteria in the ejaculate must be at least tenfold, and preferably 100-fold or more, greater than the number in the urethra for any single bacterial species (Ling, 1990). As a general rule, large numbers of bacteria (>105/ml) and high white blood cell numbers are indicative of infection. Interpretation becomes difficult if concurrent bacterial cystitis is present. Reculture after antimicrobial therapy has resolved bacterial cystitis and decreased the numbers of urethral bacteria aids in interpretation of ejaculate cultures.

FINE-NEEDLE ASPIRATION.

Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration is superior for obtaining specimens from the canine prostate for cytologic evaluation and culture. Dogs with bacterial prostatitis usually have one or more intraprostatic cysts, which can be as large as 4 cm in diameter (see Fig. 30-1) (Ling, 1990). The relationship between these cysts and bacterial prostatitis is not known; however, they provide a source of prostatic fluid for culture and cytologic evaluation and can be readily aspirated using ultrasound guidance. Cavitary prostatic parenchymal lesions greater than 0.75 cm in diameter can be aspirated transabdominally using aseptic technique and a sterile 22-gauge, 6 to 15 cm spinal needle with stylet. The needle is ultrasonographically directed to the desired location in the prostate (Fig. 30-2). Samples may be taken from cysts in the right or left lobe (or both) of the prostate. Culture results of prostatic fluid obtained by this method accurately indicate the presence or absence of infection in the prostate (Ling, 1990; Black et al, 1998). Interpretation of culture results is simple. Any bacteria that are grown should be considered pathogens as long as contamination during collection and processing has not occurred. Failure to grow bacteria implies lack of prostate infection, sampling of a uninfected area, or infection by organisms requiring special culture techniques (e.g., Mycoplasma sp.).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree