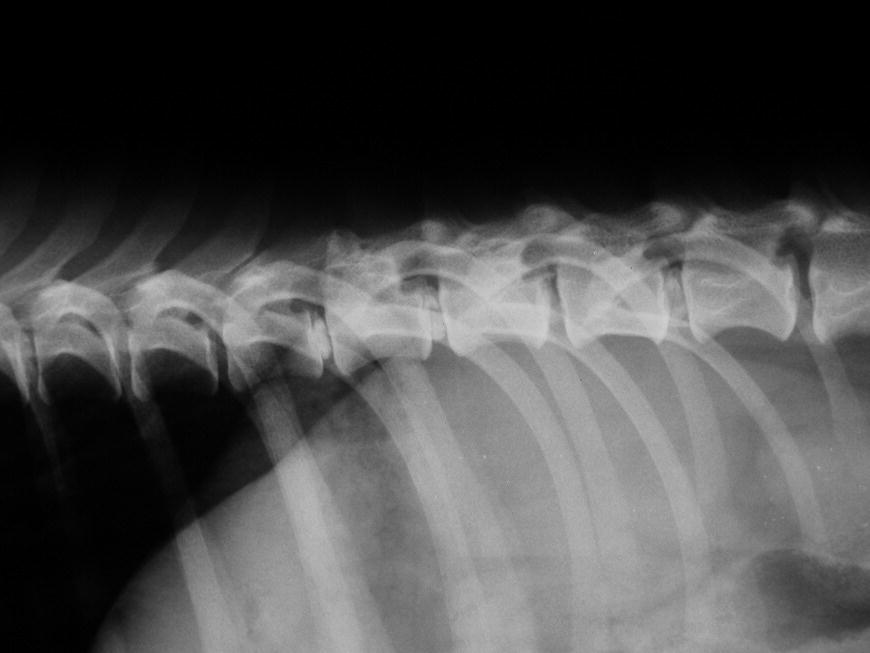

36 Franck Forterre and James M. Fingeroth Fenestration is a well-known method to attempt prevention of recurrent disc extrusion in small-breed dogs and thus possibly avoid morbidity, costs, and potential choice of euthanasia for dogs affected a second or more time after initial decompressive surgery. The decreased rate of recurrence after prophylactic fenestration shown in recent studies seems to justify its consideration as an adjunctive treatment of first-time intervertebral disc extrusion [1]. However, there are some factors that the veterinary surgeon has to consider when contemplating adding fenestration of remote discs concomitant with decompression of a herniated disc. Nonherniated intervertebral discs should not only be considered as potential sites of future extrusions but also as important spinal stabilizers. Fenestration of healthy discs not only accelerates degeneration within the fenestrated discs but also affects the spinal biomechanics (see Chapter 2). There are already some controversies as to whether stabilization should be considered after conventional decompressive surgery for disc herniation, and this deserves even more consideration if multiple adjacent levels of the vertebral column undergo fenestration and discectomy [2–4]. Although serious, clinically apparent repercussions have rarely been described after fenestration, the main goal of surgery should be to preserve function of healthy structures. Therefore, one should consider whether to routinely fenestrate all discs within a certain zone cranial and caudal to the site of decompression or selectively fenestrate only those discs that have imaging characteristics suggestive of degeneration and high potential for clinically significant herniation in the future. In this regard, the most documented risk appears to be with nonherniated discs where the nucleus pulposus is densely mineralized but there has not yet been any disc space narrowing [5] (Figure 36.1). These “plump” discs do seem more likely to become herniated at a subsequent point than those discs that have degenerated with mineralization, disc space collapse, and noncompressive herniation. The latter discs, although often the most common finding on plain radiographs, may have already reached a stage of degeneration that is less prone to future displacement of disc material into the vertebral canal. Fenestration of these discs may have less prophylactic value than anticipated. Figure 36.1 Coned-down lateral radiographic view of the thoracolumbar junction region of a chondrodystrophic dog’s spine. Note the mineralization of the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral discs at T10–T11, T11–T12, and T13–L1 and the absence of associated disc space collapse. None of these discs are currently herniated (verified with advanced imaging), reinforcing the importance of distinguishing disc disease/degeneration from disc herniation. Note also that there is collapse of the disc space at T12–T13, with absent mineralization. On advanced imaging, this was confirmed to be the site of clinically relevant herniation. However, in the dachshund breed in particular (and less well documented in other chondrodystrophic breeds), the mineralized discs without collapse represent a risk for subsequent herniation (as compared with mineralized discs where disc space narrowing has already occurred), and images such as this would justify consideration of prophylactic treatment of the nonherniated discs in conjunction with therapeutic decompressive surgery at the herniated level. The risk of recurrence is also different between canine breeds, and the definition of recurrence varies in the literature. In some publications, recurrence is defined as any new signs of neck or back pain (with or without neurologic deficits and with or without proving a disc-based cause), while in others it might include only patients with neurologic deficits but without documentation of compressive lesions [6–11]. It is also important to remember that recurrent signs in dogs that have not previously undergone decompressive surgery do not imply that each episode of clinical signs is due to a new disc level. More common, in our opinion, is recurrence of signs associated with the same

Pros and Cons of Prophylactic Fenestration: The Potential Arguments Against

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree