CHAPTER 6 Progress on Diagnosis of Retroviral Infections

Retroviral infections are lifelong and have significant impact on the health and welfare of infected cats. To prevent new infections and optimize health care for infected cats, the American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) believes that the retroviral status of all cats should be known, and recommends testing cats for retrovirus infection when they are newly acquired, sick, prior to vaccination for FeLV or FIV, or when exposed to potentially infected cats.1 Although point-of-care testing for FeLV and FIV infection is readily available, relatively inexpensive, and easily performed, less than 25 per cent of cats in the United States have ever been tested.2

FELINE LEUKEMIA VIRUS

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

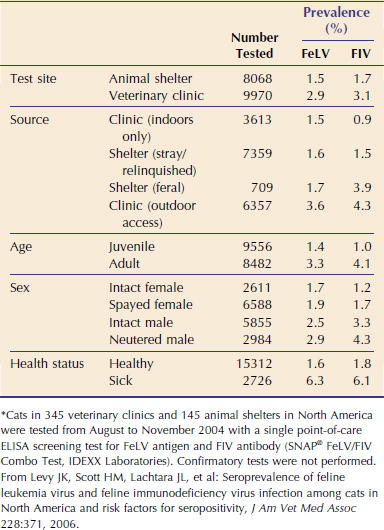

Household clusters of lymphoma and lymphocytic leukemia led to the discovery of FeLV more than 40 years ago.3 Although FeLV is one of the most common infectious diseases of cats around the world, the prevalence of infection has been decreasing since the 1980s.4–6 The decline most likely is a result of widespread test and removal/segregation programs and availability of FeLV vaccines. In the United States, recent studies report prevalences of FeLV infection ranging from less than 2 per cent for healthy cats up to 15 per cent for high-risk cats and cats tested during illness.2,4–6 In a recent survey of more than 18,000 North American pet and feral cats tested in veterinary clinics and animal shelters,5 the overall prevalence was 2.3 per cent. Infection rates were higher in pet cats than in shelter cats, and lower in healthy feral cats compared with healthy outdoor pet cats (Table 6-1). Risk factors for infection included male gender, adulthood, illness, and outdoor access. Infection rates were highest among sick feral cats, followed by sick pet cats allowed access to the outdoors.

FeLV contains a single-stranded RNA genome that encodes several major protein groups: gag (group-specific antigens), pol (reverse transcriptase), and env (envelope). Once the viral RNA genome is reverse-transcribed into DNA within infected cells, the DNA copies are inserted randomly into the host genome, and the integrated provirus is retained during cellular division. Natural FeLV infection primarily is a concern for cats who socialize with other cats and for kittens who acquire infection from their mothers. In addition to prepartum and postpartum transmission, the virus is transmitted commonly between cats via the oronasal route and by bite wounds. The prevalence of FeLV in cats with bite wound abscesses is very high (8.8 per cent).2

Much of the knowledge regarding FeLV pathogenesis has been provided by studies of experimental infections. Based on virus culture and antigen testing, it was generally believed for many years that approximately one-third of infected cats remain persistently infected, whereas up to two-thirds develop an effective immune response with eventual recovery from infection. However, recent studies utilizing highly sensitive real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques have redefined the outcomes of FeLV infection and suggest that cats most likely remain infected for life.8–14 FeLV proviral DNA and viral RNA transcripts are detectable by PCR in circulating lymphocytes and monocytes within 1 week of infection, even if viral antigen is not.8,11–14 Regardless of the eventual outcome of infection, all cats appear to develop similar proviral and plasma viral RNA loads during the early phase.8–14

In progressive infection, insufficient FeLV-specific immunity results in extensive virus replication that occurs first in the lymphoid tissues and then in the bone marrow.15,16 Spread to mucosal and glandular tissues and excretion of infectious virus in various secretions (saliva, feces, urine, milk) occur at about the same time as bone marrow infection. Bone marrow infection results in a secondary viremia in which all leukocyte subsets and platelets contain high proviral DNA and RNA loads.14 These cats are persistently viremic and antigenemic, and succumb to FeLV-associated diseases within a few years (Table 6-2).

Table 6-2 Infection Outcomes for Cats Exposed to FeLV*

* The FeLV status of the cats was determined by soluble antigen testing, IFA testing for intracellular antigen, virus culture, and real-time PCR analysis.

Modified from Levy J, Crawford C, Hartmann K, et al: 2008 American Association of Feline Practitioners’ feline retrovirus management guidelines, J Feline Med Surg 10:300, 2008.

In regressive infection an effective immune response limits virus replication prior to bone marrow infection.15,16 FeLV antigen and infectious virus usually are detectable in peripheral blood for 2 to 3 weeks after virus exposure, but then disappear 2 to 8 weeks later or, in rare cases, after many months. However, these cats have not cleared the infection. PCR assays have shown that circulating lymphocytes contain low amounts of proviral DNA and RNA transcripts (see Table 6-2).10–14 The clinical relevance of regressive infections is not yet clear. Cats with regressive infection do not shed virus and are unlikely to develop FeLV-associated diseases.13,14 Even though viral shedding does not occur, it is possible that cats with regressive infection can still transmit FeLV via blood and tissue donation, because the proviral DNA might be infectious. In addition, recurrence of viremia and subsequent clinical disease have been observed in some cats.10,11 Research on the possible outcomes for FeLV exposure is ongoing and controversial, but underpins new recommendations for diagnostic testing. As more information emerges, the outcomes likely will continue to evolve and be refined, along with diagnostic approaches.

DIAGNOSIS

The FeLV p27 gag protein is abundant in the plasma and cytoplasm of infected cells during the acute phase of infection and in progressively infected cats. Detection of circulating p27 protein is the basis for rapid-screening test kits used with serum, plasma, and whole blood. These kits are available in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and membrane immunochromatography formats for use in veterinary clinics, animal shelters, and diagnostic laboratories. The soluble antigen screening tests usually are positive within 30 days of viral exposure, but development of antigenemia is variable, especially in cats with regressive infection. Kittens may be tested at any time because passively acquired maternal antibody to FeLV does not interfere with testing for viral antigen. However, kittens infected as a result of maternal transmission may not test positive for weeks to months after birth.17

Recent studies18–20 have found acceptable diagnostic accuracy for several commercially available screening tests for soluble FeLV p27 antigen; sensitivities (proportion of positive results for infected cats) range from 92 to 94 per cent, and specificities (proportion of negative results for uninfected cats) range from 92 per cent to greater than 99 per cent. Negative screening test results are reliable because of the high sensitivity of the tests and low prevalence of infection (negative predictive value >99 per cent). If the results of soluble antigen testing are negative but recent exposure can not be ruled out, antigen testing should be repeated a minimum of 30 days after the last potential exposure. However, a negative soluble antigen test result does not rule out the possibility that a cat has regressive infection. Detection of regressively infected cats requires testing a blood sample for FeLV DNA using a PCR assay (see the following). Recent studies using real-time PCR have shown that 5 to 10 per cent of cats with negative results on soluble antigen tests were positive for FeLV provirus by PCR.7,21

The positive predictive value (probability that a cat with a positive result is truly infected) of currently available screening tests for FeLV p27 is low (<90 per cent), especially in low-risk and asymptomatic patients.18,19 Importantly, the two most widely used point-of-care tests in the United States, Witness FeLV Test (SynBiotics Corporation, Kansas City, MO) and SNAP FeLV/FIV Combo Test (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME), have a positive predictive value of only 74 per cent.18,19 Therefore confirmatory testing of positive screening test results is recommended. Multiple options exist for confirmation of a positive screening test result. Initially, antigen testing can be repeated, preferably using a test from a different manufacturer.7–19 In a recent comparative study,19 testing samples with a combination of soluble antigen tests from different manufacturers improved the positive predictive value to nearly 90 per cent. Another option for verification of positive screening tests is performance of an immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) test on blood or bone marrow smears. The IFA test detects viral p27 antigen within infected leukocytes and platelets subsequent to bone marrow infection in cats with progressive infection. False-negative IFA results can occur when neutropenia or thrombocytopenia is present. In general soluble antigen tests are considered to be slightly more sensitive (fewer false-negatives), and the IFA test to be slightly more specific (fewer false-positives).

Virus isolation generally has been accepted as the reference test or gold standard for confirmation of FeLV antigen screening tests. This assay detects replication-competent infectious virus and therefore usually agrees with antigen screening test results. In one recent study,20 about 25 per cent of cats tested by antigen detection assays and virus isolation had discordant results. Cats who tested positive for p27 antigen but negative by virus isolation were retested using a real-time PCR assay for FeLV proviral DNA. About 50 per cent of these cats were FeLV-positive by PCR, suggesting the possibility of regressive infections. The other 50 per cent who tested negative for FeLV DNA may have been falsely positive on the antigen test because these latter tests for FeLV have a lower positive predictive value.

PCR is a highly sensitive test for FeLV DNA, but also is highly susceptible to technical errors, contamination during sample collection and handling, and poor quality control, any of which reduce the accuracy of results. At this time, there are no reports comparing the reliability and accuracy of FeLV PCR tests offered by different commercial laboratories. When performed under optimal conditions, real-time PCR is the most sensitive test methodology for detection of FeLV DNA (detection limit of five to 10 copies) and can help to resolve the status of patients with discordant antigen test results or when infection is suspected but not confirmed by antigen testing. PCR can be performed on blood, bone marrow, and tissues. In addition PCR testing of saliva has been shown to have high correlation with blood antigen tests.21 Because cats with regressive infection can transmit FeLV proviral DNA that may be infectious, all feline blood and tissue donors should be tested for FeLV antigen by serology and for provirus by real-time PCR.

Because FeLV tests are based on detection of antigen or DNA and not antibodies, vaccination against FeLV generally does not interfere with testing. However, blood collected immediately following vaccination may contain detectable FeLV vaccine strain antigens or DNA.9–11 The extent and duration of vaccine interference with testing is unknown, but diagnostic samples should be collected prior to starting the vaccination series. Cats also should be tested before vaccination because administration of FeLV vaccines to infected cats is not believed to have any value. With the advent of highly sensitive PCR testing, some vaccinated cats have been identified as infected after viral exposure. These cats had regressive infection demonstrated by PCR detection of circulating proviral DNA and plasma viral RNA, in the absence of antigenemia or viremia.9–11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree