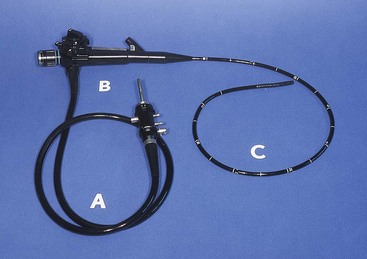

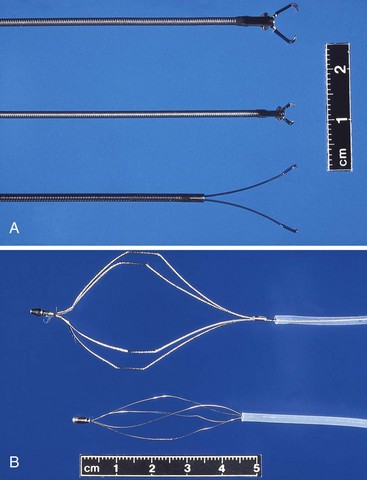

Chapter 13 Although flexible endoscopy of the alimentary and respiratory tracts occasionally is performed to dilate a stricture, control hemorrhage, remove part or all of an organ, insert a tube, or remove a foreign object, its primary use in veterinary medicine is to visualize and obtain tissue or cytologic samples (Box 13-1). Biopsy should always be performed regardless of the gross mucosal appearance unless there is a specific reason not to biopsy (e.g., coagulopathy, increased risk of perforation). Tissue samples obtained by flexible endoscopy are limited to the mucosa and adjacent submucosa as opposed to the full-thickness samples obtained surgically. However, endoscopic samples are typically adequate for diagnosis in probably >90% of patients (personal observation of author M.D.W.) with gastric or intestinal infiltrative disease (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, histoplasmosis, neoplasia), assuming the operator has been well trained. Endoscopy cannot diagnose disorders beyond its reach (e.g., focal carcinoma of mid-jejunum). Nor can endoscopy reliably diagnose infiltrates that are too deep in the mucosa for the endoscopic biopsy forceps to reach or those that are hard, densely fibrotic lesions (e.g., pythiosis, scirrhous carcinoma). Percutaneous placement of gastrostomy feeding tubes can be done with or without endoscopy (see p. 107). Endoscopic placement of such tubes is indicated when the nonendoscopic apparatus for placement cannot be safely passed through the esophagus (e.g., esophageal stricture, esophageal dilation), when the operator is inadequately trained in the use of nonendoscopic apparatus, or when the endoscope is already in the stomach for other purposes. Endoscopic placement includes insufflation of the stomach, which is advantageous because insufflation helps prevent other abdominal organs from becoming trapped between the stomach and the abdominal wall. Rigid endoscopy can be used for the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, urinary bladder, peritoneal cavity, pleural cavity, and joints. Indications for rigid endoscopy include many of those for flexible endoscopy (see Box 13-1), but rigid endoscopy (especially laparoscopy, thoracoscopy, and arthroscopy) is used more often than flexible endoscopy for interventional procedures. Endoscopes: The equipment needed depends on the type of endoscopy and the body system to be investigated. Rigid and flexible endoscopes are available in a large assortment of sizes and lengths; both types have advantages and disadvantages (Box 13-2). Flexible endoscopes most often used in veterinary medicine are gastroduodenoscopes, bronchoscopes, and colonoscopes. Flexible scopes have a handle, an insertion tube, and an umbilical cord (Fig. 13-1). Bronchoscopes usually have a 2- to 6-mm outer diameter, gastroduodenoscopes a 7.9- to 10-mm outer diameter, and colonoscopes a 10- to 16-mm outer diameter. All scopes should have a biopsy-suction channel (usually 2 mm in diameter for bronchoscopes and 2- to 3.2-mm for gastroduodenoscopes and colonoscopes). Gastroduodenoscopes and colonoscopes have four-way deflection of the tip of the scope and an air-water channel that is used to insufflate air and wash off the viewing lens; bronchoscopes and ultrathin gastroduodenoscopes typically have only two-way deflection of the tip. Bronchoscopes do not have an air-water channel. The insertion tube typically has a working length of 40 to 60 cm in bronchoscopes, 100 to 135 cm in gastroduodenoscopes, and 130 to 220 cm in colonoscopes. Biopsy/cytology equipment: Biopsy and foreign body retrieval forceps for flexible scopes come in various shapes. The size of the forceps depends on the size of the biopsy aspiration channel; the larger the channel, the bigger and stronger the biopsy or retrieval device that can be used. If possible, a scope with a 2.8-mm channel should be used for most alimentary tract endoscopy in dogs and in cats weighing more than 3 to 4 kg. The tissue sample obtained through a 2.8-mm channel can be more than twice the size of a sample obtained through a 2-mm channel. These larger pieces of alimentary tissue can easily contain the full thickness of the mucosa and often some submucosa. The author (M.D.W.) prefers fenestrated biopsy forceps in an ellipsoid, alligator jaw configuration without a needle (Fig. 13-2); however, other endoscopists have other preferences that work for them. Disposable biopsy forceps are widely used in human medicine but seem to offer no real advantage in veterinary medicine. Interventional tools for flexible endoscopes: A variety of special retrieval instruments are necessary to reliably remove most commonly encountered foreign objects. The most useful devices are a coin retrieval (W-type) forceps, a shark’s tooth forceps (especially useful for firmly grabbing cloth), an alligator jaw forceps, and a four- or six-wire basket (Fig. 13-3). The basket should be made of very flexible wire to facilitate passage over and around an object; however, this quality also makes it easier to bend the wire and ruin the basket. Other retrieval devices include wire snares, three-wire grabbers, magnetic-tip probes, and forceps with nonskid rubber; these instruments are seldom required.

Principles of Minimally Invasive Surgery

Endoscopy: General Principles, Equipment, and Techniques

Indications

Flexible Endoscopy

Rigid Endoscopy

Equipment

Flexible Endoscopes

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree