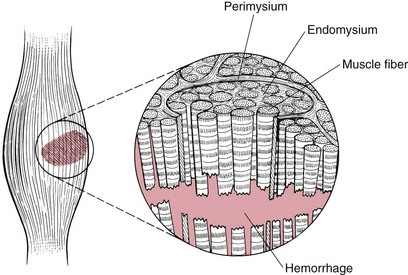

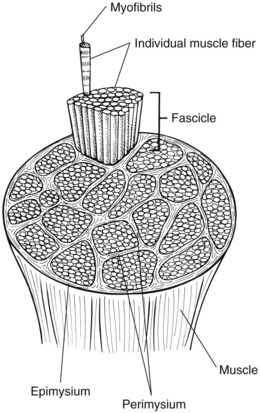

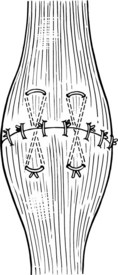

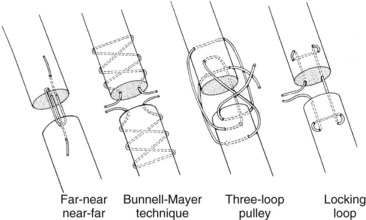

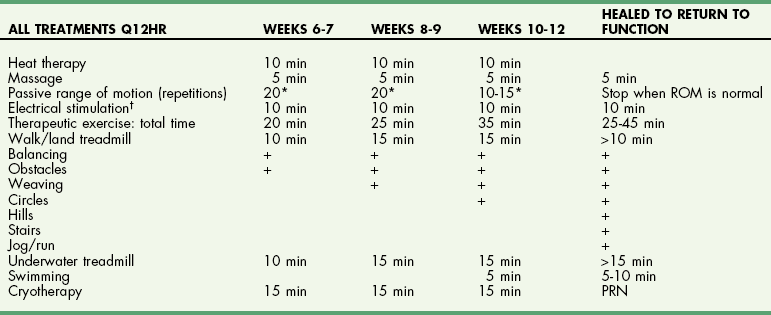

Chapter 35 General Principles and Techniques Compartment syndrome of muscles occurs when pressure increases within a nonextensible fascial compartment usually as the result of bleeding in the compartment following trauma. The increased pressure may cause irreversible damage to the muscle and nerves within the compartment. Compartment syndrome secondary to hemangiosarcoma has been reported in two dogs (Bar-Am et al, 2006; Radke et al, 2006). Clinical signs depend on the severity and chronicity of injury. With mild contusions, the animal may exhibit minimal lameness and the source of pain may be difficult to find on examination. With more severe contusions, pain and swelling are present. Most severe contusions occur in conjunction with fractures, and although the focus is on the fractured bone, injury to the muscle should be evaluated during surgery. Severe muscle strains are recognized by swelling and pain of the affected muscle unit (Fig. 35-1). Chronic muscle strains (e.g., bicipital tenosynovitis, iliopsoas muscle injury) occasionally occur in dogs. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used to diagnose muscle strain in dogs. MRI changes have been identified in dogs with iliopsoas (Ragetly et al, 2009) and gastrocnemius (Stahl et al, 2010) myotendinous strains. Muscle contusions and strains must be differentiated from joint sprains, fractures, polymyopathies, and polyarthropathies. Physical examination often differentiates muscle injury from joint sprain. Gentle palpation of muscle contusions causes pain and identifies swelling, whereas pain associated with sprain is elicited on manipulation of involved joints. Arthrocentesis (see p. 1239) helps differentiate joint sprain or arthropathy from muscle injury. The primary treatment for muscle contusion and strain is rest. Enforced rest with controlled activity is necessary for at least 3 weeks. If injury is recurrent or severe, longer periods of enforced rest may be necessary. If the muscle is not allowed to heal adequately, repeated injury is likely. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (see Table 34-4 on p. 1221) can be administered for the first 3 to 4 days, but restricted activity must continue even if lameness and pain disappear. When a severe contusion is recognized during surgical stabilization of a fracture, decompression of the muscle compartment can be achieved through incision of the epimysium (see p. 1377). Surgical treatment is necessary only if interstitial fluid accumulation causes sufficient pressure to compromise blood flow (i.e., compartment syndrome). Compartment syndrome has been diagnosed rarely in dogs and has not been reported in cats. Fibrotic contracture of the infraspinatus muscle may be a sequela of osteofascial compartment syndrome in dogs (Devor et al, 2006). Skeletal muscle is made of long, cylindrical fibers encased within connective tissue sheaths (Fig. 35-2). Each individual fiber is enclosed within a sheath called the endomysium. Each fiber bundle is also enclosed within a sheath (perimysium), as is the entire muscle (epimysium). The connective tissue sheaths house blood vessels and nerve fibers that serve to integrate muscle contraction of individual fibers. Muscles are attached to bone by cordlike tendons or flat aponeuroses. The fascial compartment overlying the muscle group appears tight and congested with contusions, and the underlying muscle appears severely bruised and often protrudes from the incision through the fascial compartment. Self-retaining retractors are useful for retracting soft tissue from the area of interest. Bar-Am, Y, Anug, AM, Shahar, R. Femoral compartment syndrome due to haemangiosarcoma in the semimembranosus muscle in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2006;47:286. Devor, M, Sørby, R. Fibrotic contracture of the canine infraspinatus muscle: pathophysiology and prevention by early surgical intervention. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2006;19:117. Radke, H, Spreng, D, Sigrist, N, et al. Acute compartment syndrome complicating an intramuscular haemangiosarcoma in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2006;47:281. Ragetly, GR, Griffon, DJ, Johnson, AL, et al. Bilateral iliopsoas muscle contracture and spinous process impingement in a German Shepherd dog. Vet Surg. 2009;38:946. Stahl, C, Wacker, C, Weber, U, et al. MRI features of gastrocnemius musculotendinopathy in herding dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2010;51:380. Muscle-Tendon Unit Laceration Muscle-tendon lacerations must be differentiated from superficial lacerations and muscle strain (see p. 1375). Thoroughly débride the wound edges to fresh, bleeding muscle (Fig. 35-3). Débride carefully to prevent excess removal of tissue, which makes apposition of the severed ends difficult. Place interrupted sutures in the outer muscle sheath around the circumference of the muscle. Support the appositional sutures with heavy stent sutures placed in a cruciate pattern. Delicately manipulate and débride the tendon ends. With small, flat tendons, use small-diameter, nonabsorbable material placed in a series as interrupted vertical mattress or cruciate sutures. For larger tendons, select the largest suture diameter that will readily pass through the tendon atraumatically. A locking-loop suture pattern is recommended (Fig. 35-4). Place each loop of the pattern in a slightly different plane (i.e., near-far, middle-middle, and far-near pattern). Alternatively, use a three-loop pulley or a Bunnell-Mayer, far-near, or near-far suture pattern. Use adjoining fascia to support the tendon appositional sutures. After tendon repair, the limb should be immobilized for 3 weeks with the use of rigid external coaptation or external fixation with the joint positioned to release stress on the repaired tendon (see p. 1067). However, placement of an external fixator has not been demonstrated to significantly decrease strain in the Achilles tendon (Lister et al, 2009). When the splint is removed, the limb should be semi-rigidly immobilized for an additional 3 weeks with a heavy padded bandage or a half cast (i.e., one side of a split cast applied cranially or caudally to the limb). If an external fixator was used, it may be dynamized by the use of hinges or resistance bands. Hinges placed at the center of rotation of the joint can be adjusted to increase the range of motion and subsequently the tendon load. Elastic bands placed between the pins above and below the joint to replace the side bars allow partial loading of the tendon. After muscle repair, the limb should be immobilized for 5 days, followed by 4 to 6 weeks of protected activity. The use of platelet-rich plasma is under investigation as an aid in the healing of muscle and tendon in dogs (see Chapter 14). During immobilization, pulsed 3 MHz therapeutic ultrasound may aid in collagen repair. After immobilization for muscle or tendon lacerations, physical rehabilitation is vital to reverse the effects of immobilization on the other joints (Table 35-1). The animal should be gradually returned to normal activity; premature weight bearing will result in failure of the tendon to heal. Sample Physical Rehabilitation Protocol for Patients With Muscle-Tendon Unit Laceration +, Perform modality; PRN, as needed; ROM, range of motion. Begin no sooner than 6 weeks postoperatively, after external coaptation is no longer needed. *Passive range of motion to all joints of the affected limb. †Electrical stimulation to be performed on affected muscle groups. See Chapter 12 for specifics. Return to normal function is expected if postoperative recommendations are followed (Worth et al, 2004). Failure generally is associated with allowing the animal to exercise before the tendon has completely healed. Lister, SA, Renberg, WC, Roush, JK. Efficacy of immobilization of the tarsal joint to alleviate strain on the common calcaneal tendon in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2009;70:134. Worth, AJ, Danielsson, F, Bray, JP, et al. Ability to work and owner satisfaction following surgical repair of common calcanean tendon injuries in working dogs in New Zealand. N Z Vet J. 2004;52:109. Kramer, M, Gerwin, M, Michele, U, et al. Ultrasonographic examination of injuries to the Achilles tendon in cats and dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2001;42:531. Lamb, CR, Duvernois, A. Ultrasonographic anatomy of the normal canine calcaneal tendon. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2005;46:326. Millis, DL, Levine, D, Taylor, RA. Canine rehabilitation and physical therapy. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004. Moores, AP, Comerford, EJ, Tarlton, JF, et al. Biomechanical and clinical evaluation of a modified 3-loop pulley suture pattern for reattachment of canine tendons to bone. Vet Surg. 2004;33:391. Moores, AP, Owen, MR, Tarlton, JF. The three-loop pulley suture versus two locking-loop sutures for the repair of canine Achilles tendons. Vet Surg. 2004;33:131. Worth, AJ, Danielsson, F, Bray, JP, et al. Ability to work and owner satisfaction following surgical repair of common calcanean tendon injuries in working dogs in New Zealand. N Z Vet J. 2004;52:109.

Management of Muscle and Tendon Injury or Disease

Muscle Contusion and Strains

General Considerations and Clinically Relevant Pathophysiology

Diagnosis

Physical Examination Findings

Diagnostic Imaging

Differential Diagnosis

Medical Management

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Anatomy

Suture Materials and Special Instruments

References

Differential Diagnosis

Surgical Technique

Tendon Laceration

Postoperative Care

Physical Rehabilitation

![]() TABLE 35-1

TABLE 35-1

Prognosis

References

Management of Muscle and Tendon Injury or Disease