Chapter 114Prepurchase Examination of the Performance Horse

Contract

Purchaser’s Reservations

The veterinarian is responsible for the following:

Communication with the Vendor

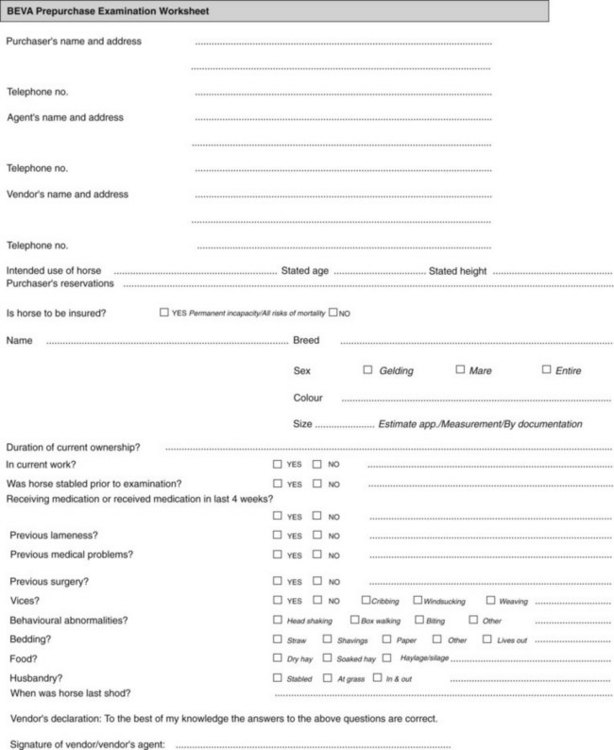

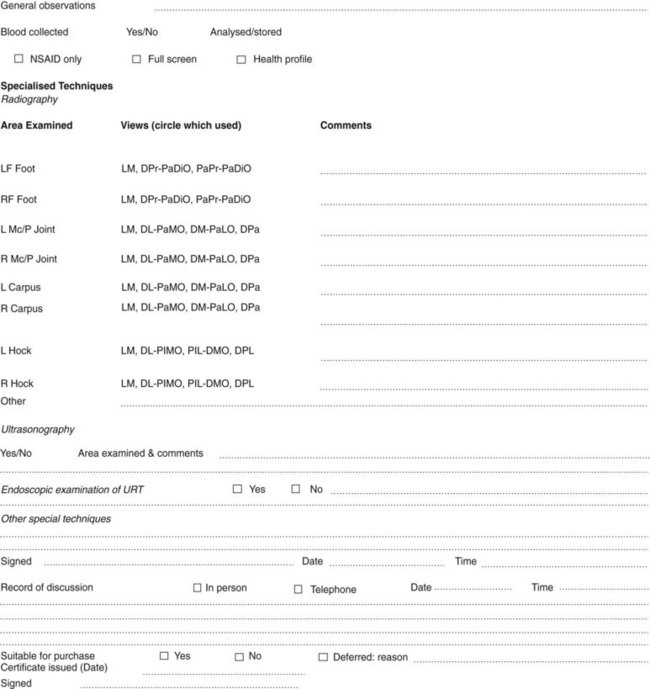

Ideally vendors should sign a copy of their responses to these questions (Figure 114-1).

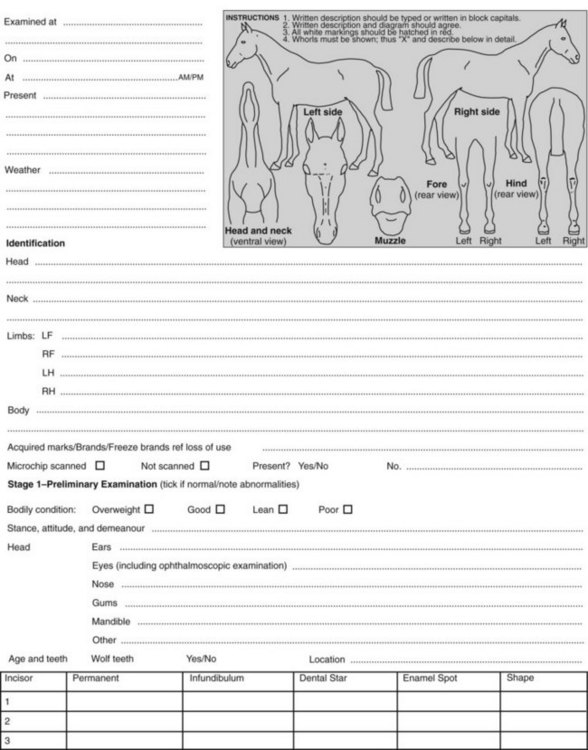

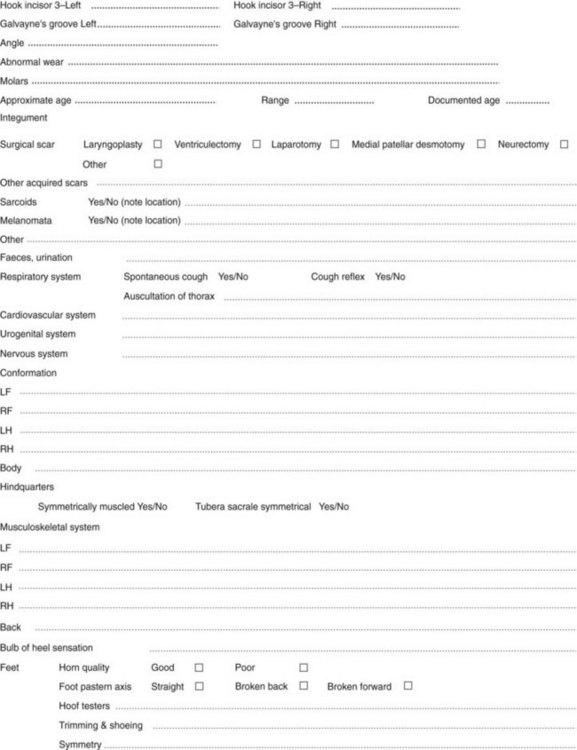

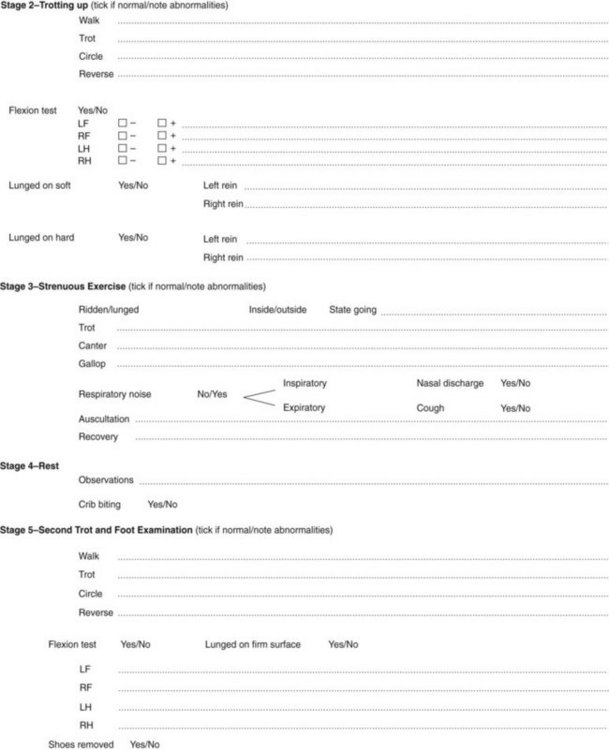

Clinical Examination at Rest

The horse first should be examined in the stable, with assessment of demeanor, attitude, stance, and conformation and thorough observation and palpation of the head, neck, back, and limbs as described in Chapters 4 to 6. Collection of blood samples may be performed at this stage or when the examination is completed and the veterinarian deems that purchase will probably be recommended. More comprehensive evaluation of the feet, overall conformation, and evaluation of muscle symmetry is best performed outside, where the horse can be viewed better from all angles.