CHAPTER 60Premature Lactation in Mares

Premature lactation in the pregnant mare can be defined as development of the mammary gland or milk production, or both, a minimum of 2 weeks before parturition. This condition is a dreaded clinical sign for the equine practitioner because it often is associated with impending abortion. The most common causes of premature lactation are twin pregnancies and bacterial placentitis. Uterine body pregnancies also may manifest with premature lactation1; however, the incidence of uterine body pregnancies is substantially lower than that of twins or bacterial placentitis. Abortion due to other causes (viral, fungal, or functional) generally occurs earlier in gestation and is not associated with udder development. Differentiating among the causes of premature lactation poses a challenge to the veterinary practitioner. Methods for diagnosing and managing causes of premature lactation are reviewed in this chapter.

HISTORY AND CLINICAL SIGNS

Photoperiod can affect the length of gestation,2 thereby influencing mammary development relative to parturition. Without knowledge of the typical gestational length of a given mare, it may be difficult to know when appropriate gland development should begin. Fortunately, most mares have approximately the same gestation length from year to year, so interpreting mammary development based on gestation length is more reliable in these mares. The one caveat to use of this rule of thumb is that season can affect length of the gestational period in a given mare. Specifically, a mare with an average gestation length (i.e., 333 to 342 days)3 during days with maximal light may have a longer gestational period during days with minimal amount of light. Therefore, obtaining accurate breeding and foaling history for a mare can be critical in differentiating normal from abnormal mammary gland development.

Precocious mammary development may or may not be accompanied by spontaneous milk release (i.e., “streaming”). This should be differentiated from both the dried serous exudates (“waxing”) commonly seen on the teats of mares nearing parturition and the serous to slightly milky secretions that can be expressed from teats of nonpregnant and prepubertal animals (“witch’s milk”). The ramifications of premature milk release are multiple. Of paramount importance, this clinical sign most commonly is associated with an abnormal pregnancy. In addition, premature milk release results in loss of important immunoglobulins, which can be detrimental to survival of a neonate.4,5 If premature milk release is identified, diagnosis and treatment of the inciting cause should be performed immediately. If possible, milk can be passively collected as it streams from the udder (and then frozen).

Colostrum and milk quality should be monitored at the time of delivery to ensure that immunoglobulin content is adequate. Colostrum quality can be evaluated using a colostrometer (Lane Manufacturing, Denver, Colorado)6 or wine refractometer (Bellingham & Stanley, Kent, England).7 Colostral specific gravity is measured using a colostrometer. Specific gravity of equine colostrum has been shown to have high correlation with immunoglobulin content (i.e., >3000 mg/dl with specific gravity >1.06).8 An additional simple method for evaluating colostral quality involves measuring total proteins using a refractometer specific for sugar or alcohol.7 Such refractometers have the necessary range of refraction to facilitate accurate measurement of colostral proteins. A reading of more than 23% sugar or 16° alcohol is consistent with good-quality (>60 g/L) colostrum.7 Before use of either a colostrometer or a refractometer, both the equipment and the colostrum sample should be at room temperature to ensure an accurate reading.

Vulvar discharge sometimes is present in mares with abnormal pregnancy. Vulvar discharge and precocious mammary development typically occur together, but each symptom can be present independently. Bacterial placentitis is the most frequent cause of vulvar discharge. Vaginitis or abortion due to other causes (viral or fungal) also may cause vulvar discharge, although less frequently. If vulvar discharge is present, a swab for bacterial identification and antimicrobial sensitivities should be obtained. A direct swab from the discharge is useful for screening purposes. An additional swab of discharge noted in the cranial vagina or at the external cervical os also should be obtained. These samples may provide a more definitive identification of a specific organism if obtained under aseptic conditions. Taking swabs from the cervical lumen or uterus is contraindicated because of the potential to penetrate the cervix, with accompanying risk of disrupting the pregnancy.

DIAGNOSIS

Transrectal Ultrasonographic Evaluation

Transrectal ultrasonography in late gestation is useful primarily for evaluating placental integrity at the cervical star, fetal fluid character, and limited evaluation of the fetus (i.e., activity, orbit diameter). Examination for twin pregnancies in late gestation using transrectal ultrasonography is highly unreliable—in direct contrast with the proven usefulness of this modality early in gestation, allowing prompt diagnosis and management of twin pregnancies.9

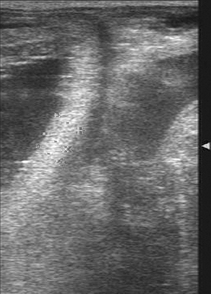

In late gestation, transrectal ultrasonography of the caudal allantochorion provides an excellent image of the placenta close to the cervical star.10 This region is affected most frequently in cases of ascending placentitis. In the normal pregnant mare, the area visualized in the region of the cervical star is the combined uterine and placental (chorioallantoic) unit. Renaudin and co-workers10,11 developed the technique for evaluation of the combined thickness of the uterus and placenta (CTUP) and established normal values in light horse mares throughout gestation. To perform the procedure, any fecal material is evacuated from the mare’s rectum. The reproductive tract should be manipulated minimally to avoid stimulating the fetus. A 5- or 7.5-MHz linear transducer is placed in the rectum and positioned 5 cm cranial to the cervical-placental junction. The transducer is moved laterally until the large uterine vessel (possibly the middle branch of the uterine artery) is visible at the ventral aspect of the uterine body.10 The CTUP is measured between the uterine vessel and the allantoic fluid (Figure 60-1). A minimum of three measurements should be obtained and averaged.

Figure 60-1 Transrectal ultrasound measurement of the combined thickness of the uterus and placenta (CTUP).

It is important to obtain all CTUP measurements from the ventral aspect of the uterine body, because physiologic edema of the dorsal aspect of the allantochorion has been noted in normal pregnant mares during the last month of gestation.10 This finding may be misdiagnosed as pathologic thickening of the fetal membranes. In addition, the clinician should be sure that the amniotic membrane is not adjacent to the allantochorion, because this may result in a falsely increased CTUP. Conversely, fetal pressure on the caudal uterus can falsely decrease the CTUP. Care should be exercised to obtain measures when the fetus is not in the pelvic canal. Normal values for CTUP have been established.10 Increases in CTUP of greater than 8 mm between days 271 and 300, greater than 10 mm between days 301 and 330, and greater than 12 mm after day 330 have been associated with placental failure and impending abortion.12 Transrectal ultrasonographic examination is useful for identifying other abnormal conditions, including accumulation of purulent material (hyperechoic) between the uterus and the placenta (Figure 60-2). Measurements in such cases are meaningless because they will no longer reflect the true dimension of the combined unit and because evidence of accumulated purulent material is pathognomonic for placentitis.

Transabdominal Ultrasonographic Evaluation

Transabdominal ultrasonography is an excellent tool for evaluating the fetus and placenta in mares that are considered to be at risk for abortion during late gestation.13–15 Fetal well-being can be assessed through transabdominal ultrasonographic evaluation of fetal heart rate, tone, activity, and size. Placental membrane integrity and thickness and fetal fluid character also are evaluated using this technique. Transabdominal ultrasonography also is the most accurate method to diagnose twins in late gestation.

Before the examination, proper preparation of the patient is important. Ideally, the mare’s ventral abdomen is clipped from the mammary gland to the xiphoid process and up to the level of both stifles.16 The area is cleansed of debris. Coupling gel or alcohol is applied. In cases in which clipping the ventral abdomen is not an option, thorough (and frequent) wetting of the abdomen with alcohol generally facilitates proper examination of the abdominal contents. Ultrasonographic examination of the equine abdomen is performed using a 2.5- or 3.5-MHz transducer with a depth setting of 20 to 30 cm.13,14,16–18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree