Chapter 82 Practical Aspects of Ruminant Intensive Care

Ruminant intensive care often requires intervention, even before a diagnosis is made. The patient’s condition may be from an acute illness or injury, a chronic illness that has decompensated, or from an unexpected complication of another illness or condition. When managing complex cases, it is helpful to remember to treat the most life-threatening problems first.4

Anticipation, not reaction, has been cited as the key to successful management of severely ill animals. The Rule of Twenty was designed to assist the clinician in anticipating what might happen next with an intensive care patient. This rule is a list of 20 critical parameters that should be evaluated regularly in such cases.4,7 Using it as a guide to assess the status and therapeutic strategy, the Rule of Twenty is adapted and applied to the intensive care needs of nondomestic ruminants. Despite the usefulness of the Rule of Twenty, good intensive care must include careful consideration of the patients’ problems along with compassionate nursing care and attention to detail. The most important monitoring tools available are our own eyes, ears, hands, and stethoscope. Although advances in technology have greatly improved the ability to assess a patient’s status objectively, there is no substitute for a carefully repeated physical examination.2

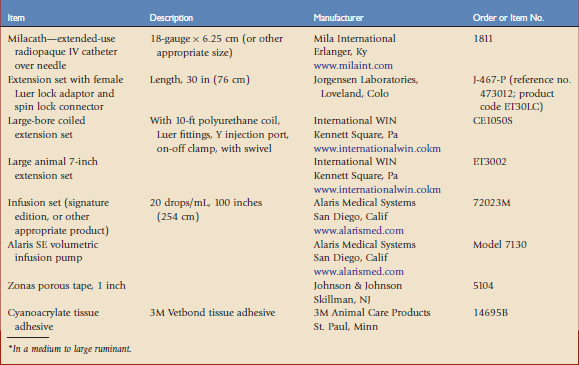

Many nondomestic ruminant species exhibit aggressive, fractious, or flighty behavior and, therefore, cannot tolerate frequent handling. The use of neuroleptics may improve patient compliance as well as decrease stress.1,10 Successful case management also hinges on the ability to deliver the appropriate therapeutic and supportive care. Placing an indwelling intravenous catheter (IVC) facilitates the remote delivery of fluids and adjunct therapies. Materials and procedures used at the Harter Veterinary Medical Center at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park are listed in Table 82-1 and Boxes 82-1 and 82-2.

BOX 82-2 Intravenous Catheter and Fluid Line Placement for Remote Delivery

Patient Preparation

Catheter Placement

Stall Preparation

Rule of Twenty for Ruminants

1 Fluid Balance

One of the most important decisions will be based on the animal’s hydration and perfusion status. The type of fluid should be chosen carefully so that it maintains adequate intravascular volume and hydration without overloading the interstitial space. Shock results when there is inadequate tissue oxygenation, most often caused by decreased perfusion. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) involves the release of vasoactive and inflammatory mediators that accompany shock; it may be initiated by bacteremia, endotoxemia, traumatic shock, localized infections, hyperthermia, hypothermia, dehydration, and hypotension. Any organ injury that causes hypoxia and the release of vasoactive or inflammatory mediators may result in SIRS. SIRS may reduce circulation to the digits and therefore laminitis is a potential sequela. Animals with SIRS diseases may require much more fluid than expected because of massive losses into the third body fluid space or into the interstitium because of the loss of endothelial integrity.7

Dehydration and poor perfusion are different problems requiring different therapeutic strategies. Perfusion deficits result from deficits in the intravascular fluid compartment, whereas hydration deficits result from deficits in the extravascular (interstitial and intracellular) compartments. Perfusion deficits are detected by changes in the heart rate, pulse intensity, capillary refill time, mucous membrane color, limb temperature, and rectal temperature. Blood pressure and central venous pressure are other ways to detect intravascular volume deficits but are used less often in conscious nondomestic ruminants. Most animals with an intravascular deficit (poor perfusion) also have concurrent extravascular deficits (dehydration). Hydration deficits are detected by changes in mucous membrane moistness, skin turgor, and urine output. Dryness of the corneas and retraction of the eyes may also be useful indicators of hydration status.4,5,7

The next step is to determine whether crystalloids, colloids, or both are the most appropriate fluid choice. Isotonic balanced crystalloids are the ideal solutions to administer intravenously to replace interstitial volume deficits. Synthetic colloids are ideal for the replacement of perfusion deficits, but are not beneficial for hydration deficits. When there are perfusion and hydration deficits, it is best to administer both crystalloids and colloids. The effectiveness of the fluid therapy may be determined by assessing and reassessing the clinical parameters listed earlier.4,5

Colloids may be used to prevent the edema that may form from redistribution of salt and water into the interstitial space. Colloid fluids are more effective blood volume expanders compared with crystalloids on an equal volume basis. Colloid therapy is indicated when total protein is less than 3.5 g/dL or the albumin level is less than 1.5 g/dL, or when therapy with crystalloids alone is likely to cause a reduction below these levels.3

2 Oncotic Pull

The loss of albumin into the interstitium because of increased vascular permeability and the addition of large volumes of resuscitative fluids in critical patients tend to reduce the blood oncotic pull and may result in massive interstitial accumulation of fluid. This fluid accumulation greatly compromises the tissue metabolism by increasing the distance between the capillary bed and the oxygen-requiring cells, and is also negatively correlated with prognosis. The use of colloids may offset this effect and help maintain vascular volume and perfusion pressure. Available colloids include blood, fresh-frozen plasma, and hetastarch. If the serum albumin level is less than 2.0 g/dL, fresh-frozen plasma is indicated. The use of synthetic plasma replacers or hetastarch may be considered if fresh plasma is not available.4,7,8

3 Glucose

Glucose in nondomestic ruminants should be maintained between 60 and 120 mg/dL, although this range is species- and age-dependent. Septic animals are at an increased risk of hypoglycemia and this condition should be considered in adult ruminants that cannot maintain adequate blood glucose levels. Acutely traumatized animals may develop insulin resistance caused by large amounts of circulating stress hormones and may develop hyperglycemia severe enough to require treatment with insulin. Hyperglycemia secondary to the use of α2 agonists should be ruled out prior to insulin therapy. Parenteral nutrition should be considered in anorectic patients to maintain adequate glucose levels.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree