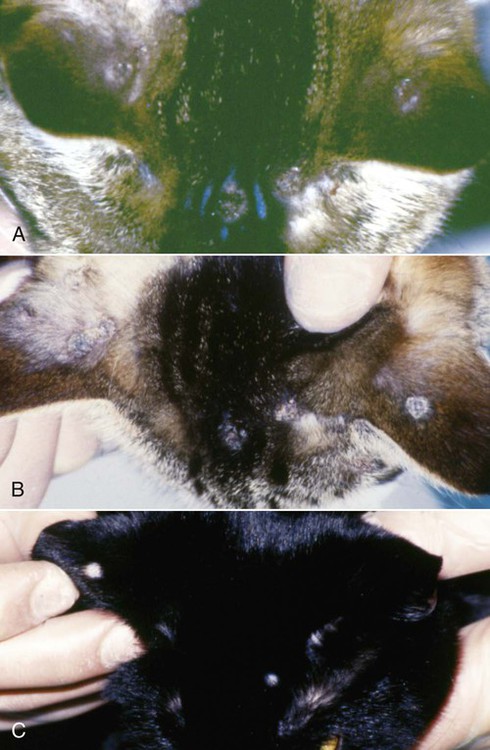

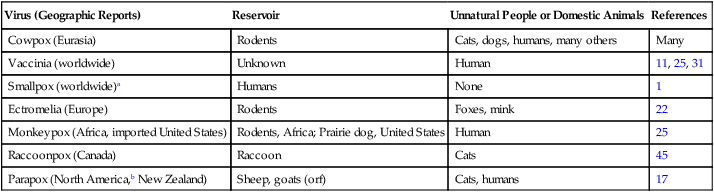

The largest viruses are poxviruses with a linear double-stranded DNA that encodes for hundreds of polypeptides. There are eight genera in the subfamily of Chordopoxvirinae under the family. The main genus is Orthopoxvirus, which includes most of the disease-causing members of people and domestic animals: smallpox virus, vaccinia virus, cowpox virus, monkeypox virus, ectromelia virus, camelpox virus, taterapox virus, and raccoonpox virus (Table 17-1). The best described and most common poxvirus infection of cats is cowpox.3 Raccoonpox has also been observed in a cat (see Clinical Findings). Members of three other genera, Parapoxvirus, Yatapoxvirus, and Molluscipoxvirus, also contain species pathogenic for mammals. Infections of cats with members of the genus Parapoxvirus7,17 and uncharacterized poxviruses in India and North America34 have been reported (see Clinical Findings). Poxviruses are relatively environmentally stable and can remain infective in dry conditions for several months to years. However, they are readily inactivated by many disinfectants, especially hypochlorites. TABLE 17-1 Features of Selected Poxviral Infections of People and Domestic Animals aEradicated through vaccination. Cowpox virus is found only in Eurasia.3 In western and northern Europe, the reservoir hosts are voles (Clethrionomys spp. and Microtus spp.) and wood mice (Apodemus spp.),* whereas in Turkmenia and Georgia the reservoir hosts are ground squirrels (Citellus fulvus) and gerbils (Rhombomys opimus and Meriones libycus).3 Despite its name, cowpox infection is uncommon in cattle, from which it was initially isolated. Although the domestic cat is the most frequently recognized incidental host,1,7,8,28,30 cowpox virus can also infect humans,4,15 cattle, horses, and various captive exotic mammals.3 A small number of cases have also been reported in domestic dogs.8 Domestic rats (Rattus norvegicus) and house mice (Mus musculus) also may be rare incidental hosts. Feline cowpox is seen primarily in rural cats that hunt rodents, and most cases are seen in summer and autumn6,8 when the opportunities for infection from the wildlife hosts are greatest. No sex or age predisposition to infection exists. Occasional cat-to-cat transmission occurs, as does cat-to-human transmission.4 Reports of natural orthopoxvirus infection in wild or domestic dogs are rare, although specific antibodies were found 6% to 20% of foxes in Germany.22,28 Intradermal inoculation of 2 × 105 plaque-forming units of cowpox virus into red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) produced mild skin lesions with minimal viral replication.9 No lesions were found after oral inoculation of virus. Another orthopoxvirus, murine ectromelia, has caused congenital disease in farm-raised silver foxes (Vulpes vulpes winter coat), blue foxes (Alopex lagopus winter coat), and mink (Mustela vison) in the Czech Republic.27 Orthopoxvirus infection was identified in a dog, a cat, and the owner in a household in Germany.44 The infection was presumed to have spread from the cat, with lesions in the dog healing after 1 to 4 months. A natural orthopoxvirus infection, characterized by ulcerative dermatitis at the site of a suspected rat bite, was identified in a domestic dog in the United Kingdom.42 This infection was likely caused by cowpox, because this has been the only orthopoxvirus in the United Kingdom since smallpox was eradicated. The natural reservoir of ectromelia virus is not known. The usual route of cowpox infection in cats is skin inoculation, probably through a bite or other skin wound, although oronasal infection is also possible.33 Local viral replication produces a primary skin lesion, and spread to the draining lymph nodes and a leukocyte-associated viremia give rise to widespread secondary skin lesions. During the viremic period, virus can be isolated from the respiratory tract. Although uncommon in domestic cats, death may be caused by viral pneumonia. Although some cats may have only a single, primary lesion, most develop secondary skin lesions within 1 to 3 weeks. First apparent as randomly distributed, small epidermal nodules, the lesions increase in size (1-cm diameter) over 3 to 5 days to form well-circumscribed ulcers, which soon become scabbed (Figs. 17-1, A and B). These gradually dry, and after 4 to 5 weeks, they exfoliate (Fig. 17-1, C). New hair growth soon occurs, although some lesions may result in small, permanently bald patches.7,8,29,32 Many cats show no clinical signs other than skin lesions. Signs of systemic illness are usually mild and occur during the viremic period just before development of secondary skin lesions. Cats may be pyrexic, inappetent, or depressed; a few may have coryza or transient diarrhea. More severe disease is rare in domestic cats and is often associated with severe bacterial infection or immune dysfunction often resulting from concurrent infection with feline leukemia virus, feline immunodeficiency virus, feline panleukopenia virus or feline herpesvirus; or from glucocorticoid treatment.7,24,24 However, in exotic felids (e.g., cheetahs), a rapidly fatal pneumonia frequently develops. Pneumonia has been described in domestic cats.23,24,37,38 Severely ill cats have a poor prognosis, and euthanasia may be advised. Feline parapoxvirus infection, probably from sheep or goats with orf, also causes multiple crusty skin lesions, which heal over a few weeks. Anecdotal accounts of similar conditions exist in North America. Infection of cats in New Zealand with orf parapoxvirus from sheep has been confirmed by polymerase chain reaction,17 and the host range of this virus should include cats.

Poxvirus Infections

Etiology and Epidemiology

Virus (Geographic Reports)

Reservoir

Unnatural People or Domestic Animals

References

Cowpox (Eurasia)

Rodents

Cats, dogs, humans, many others

Many

Vaccinia (worldwide)

Unknown

Human

11, 25, 31

Smallpox (worldwide)a

Humans

None

1

Ectromelia (Europe)

Rodents

Foxes, mink

22

Monkeypox (Africa, imported United States)

Rodents, Africa; Prairie dog, United States

Human

25

Raccoonpox (Canada)

Raccoon

Cats

45

Parapox (North America,b New Zealand)

Sheep, goats (orf)

Cats, humans

17

Pathogenesis

Clinical Findings

Cats

Cowpox Virus Infection

Parapox Virus Infection

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine