CHAPTER 31 Postmortem Examination of the Puppy and Kitten

Who Performs Postmortem Examinations?

Ideally, the entire animal is submitted to a diagnostic laboratory for complete postmortem examination. If this is not possible, the necropsy may be performed at the clinic, and collected samples can be sent to a diagnostic laboratory for testing. Some of the advantages and disadvantages of the available approaches are listed in Table 31-1.

TABLE 31-1 Pros and cons of postmortem examination at a diagnostic laboratory versus at a clinic

| Examination at | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic laboratory | Workup by specialists: gross lesions may be subtle and can be easily missed | Transport/shipping: expense and time in transit |

| Coordination of ancillary testing | Additional cost (for gross examination) | |

| Infrastructure for safe and complete examination | ||

| Carcass: prearranged disposal or cremation | ||

| Clinic | Immediate sample collection | Time consuming |

| Immediate feedback | Biosafety and containment | |

| Necropsy equipment and area | ||

| Disposal of carcass; release to client not recommended | ||

| Interpretation of findings (more often the challenge is the lack of significant gross lesions) |

Puppy and Kitten Losses and Common Causes

Box 31-1 highlights commonly encountered causes of canine and feline mortality by age group.

BOX 31-1 Common causes of mortality by age group

Abortion, Stillbirth, and Perinatal Phase (0 to 1 day)

Neonatal Phase (Puppies: 1 day to 10 days; Kittens: 1 day to 7 days)

Pediatric Phase

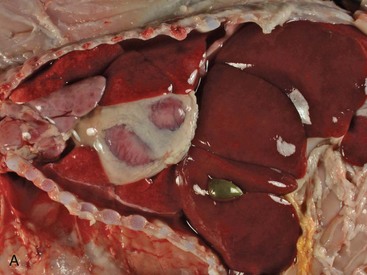

Figure 31-2 Multifocal hemorrhage, lungs, puppy. Compare these normally inflated and pink lungs with the pneumonic lungs depicted in Figures 31-3, B and 31-5. Cause of death in this puppy was septicemia.

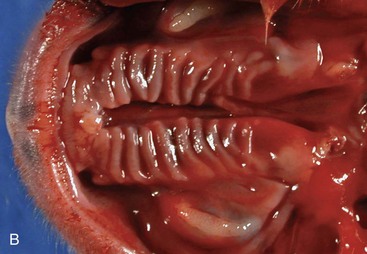

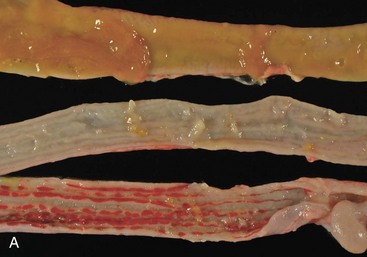

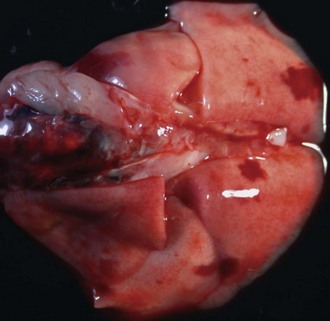

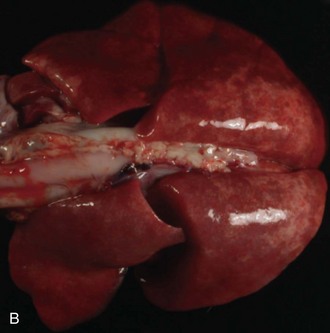

Figure 31-3 Systemic canine herpesvirus 1 infection. All the photographs in this figure show the same puppy. A, Severe acute hydrothorax and multifocal acute hepatic necrosis, situs of thoracic and cranial abdominal cavity. Pleural effusion and hepatic necrosis are common findings in herpesvirus infections. Canine herpesvirus infection is commonly diagnosed in puppies that died during the first 2 weeks of life. B, Severe acute interstitial pneumonia, lungs. The lungs are poorly collapsed and mottled red-beige. Compare with normally colored and collapsed lungs shown in Figure 31-2. C, Multifocal, severe, acute renal necrosis and hemorrhage, sagittal cut, kidney. Petechiation on the cut (left) and capsular (right) surface in the puppy is characteristic for an infection with canine herpesvirus 1.

Figure 31-5 Severe subacute bronchopneumonia, lung, puppy. This gross presentation is typical for suppurative bronchopneumonia as a result of aerogenous infection with bacteria. Bordetella bronchiseptica was isolated in this case and is the most common bacterial pathogen in feline and canine respiratory disease. Compare with normally inflated and pink lung in Figure 31-2 and interstitial pneumonia depicted in Figure 31-3, B.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree