CHAPTER 65 Plasma Cell Disorders

Plasma cell disorders represent a spectrum of neoplasms derived from a clonal proliferation of plasma cells. This leads to an accumulation of immunoglobulin (IgA, IgG, IgM, IgE, IgD)–producing B lymphocytes within hematopoietic or medullary (multiple myeloma) and extrahematopoietic or extramedullary (plasmacytoma) sites. Because these disorders are considered to arise from a single B lymphocyte, the resultant gammopathy is characteristically monoclonal; however, biclonal and polyclonal plasma cell disorders exist. The most commonly reported plasma cell diseases in cats are multiple myeloma and extramedullary plasmacytoma (EMP), respectively. Other diseases in the spectrum include monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS), a clinically benign condition, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, plasma cell leukemia, and solitary osseous plasmacytoma (SOP) (Tables 65-1 and 65-2).

Table 65-1 Definitions of Plasma Cell Disorders*

| Disorder | Definition |

|---|---|

| Multiple myeloma (MM) (see Boxes 65-1 and 65-2) | |

| Light chain myeloma | MM characterized by light chain proteinuria without monoclonal gammopathy |

| Nonsecretory myeloma | MM characterized by bone marrow plasmacytosis of >20% and skeletal lytic lesions without monoclonal gammopathy or light chain proteinuria |

| Extramedullary plasmacytoma (EMP) | One plasma cell tumor originating in soft tissues, with no skeletal lytic lesions, monoclonal gammopathy, or light chain proteinuria |

| Solitary osseous plasmacytoma (SOP); also referred to as solitary plasmacytoma of bone (SPB) | One plasma cell tumor originating in bone, with no other skeletal lytic lesions, monoclonal gammopathy, or light chain proteinuria |

| Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) | IgM monoclonal gammopathy, often with concurrent hyperviscosity syndrome, and infiltration of the liver and spleen |

| Monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS) | Monoclonal gammopathy with bone marrow plasmacytosis of <10%, with no skeletal lytic lesions, monoclonal gammopathy or light chain proteinuria, and no clinical, hematological, or biochemical abnormalities |

| Plasma cell leukemia (PCL) | >20% bone marrow plasmacytosis and >2000 plasma cells/µL in peripheral blood |

| Heavy chain disease (HCD) | Elevated M protein with an incomplete heavy chain, lacking a light chain |

* References 3, 4, 6, 10, 14–19.

Table 65-2 Commonly Used Terms*

| Term | Definition | Synonym |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal gammopathy | Elevation in a single type or component of immunoglobulin | M protein, M component, paraprotein |

| Light chain (L chain) | Lighter molecular weight polypeptide chain of antibody/immunoglobulin molecule. There are two light chains per immunoglobulin unit | κ or λ chains |

| Heavy chain (H chain) | Heavier molecular weight polypeptide chain of antibody/immunoglobulin molecule. There are two heavy chains per immunoglobulin unit | IgA, IgG, IgM, IgE, IgD |

| Fab | Fragment of antibody containing the antigen binding portion | |

| Light chain proteinuria | Excess of monoclonal light chains in urine | Bence Jones proteinuria |

| Hyperviscosity syndrome (HVS) | Sequela of increased serum viscosity secondary to increased circulating serum immunoglobulins in MM or WM. This also can be secondary to increases in RBCs or WBCs in other diseases | |

| Cryoglobulin | Proteins, often immunoglobulins, that precipitate as serum is cooled to temperatures less than body temperature and dissolve on rewarming | |

| Extramedullary | Outside of the bone marrow, in cats commonly the spleen and liver | |

| Amyloidosis | Tissue deposition of protein aggregates systemically or locally in bundles of β-sheets | AA amyloidosis—reactive AL amyloidosis—light chain |

* References 4, 6, 19–21, 28, 44.

MULTIPLE MYELOMA AND RELATED PLASMA CELL DISORDERS

INCIDENCE AND ETIOLOGY

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an uncommon disease in cats, accounting for less than 1 per cent of all malignant neoplasms in two large compilations of feline neoplasms.1,2 Similarly, in one recent report of feline MM, the disease represented less than 1 per cent of all feline neoplasms diagnosed at the Veterinary Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania from 1996 to 2004.3 Related plasma cell disorders, such as MGUS, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and plasma cell leukemia, are rare, with only a few case reports existing in the feline literature. MM is a disease of older cats (median age ≈12 years), with no breed or gender predilection. A slight increase in incidence in male cats has been suggested; however, the total number of cases reported is low, making this predilection difficult to verify.3,4

The etiology of the disease is unknown. Although the development of B lymphoid neoplasms has been associated with the prevalence of retroviruses in several domestic species, there is no association with FeLV or FIV in cats with MM.4,5 There also is no association with feline coronavirus.4 In human beings, exposure to ionizing radiation (including occupational exposure), as well as exposure to metals, benzenes, petroleum products, and silicon, have been considered potential risk factors. Familial associations have been reported in human patients and inbred mice, supporting the role of hereditary and genetic factors.6 A potential familial association was suggested in one report of a pair of sibling cats with MM.7 Chronic immune stimulation has been suggested as a predisposing factor in human beings and mice. In a case series of 24 cats with “myeloma-related disorders,” Mellor et al examined medical records for antecedent inflammatory disease. One cat had a history of severe, recurrent dental disease, and one cat had unilateral uveitis of unknown origin. No other evidence of chronic antigenic stimulation or inflammation preceding the development of the disease was found.8 In a case report of a cat with an intraocular plasmacytoma, previous trauma had occurred to the involved eye, and the authors hypothesized that chronic inflammation played a role in the development of the plasmacytoma.9 Although it is uncommon, solitary extramedullary plasmacytomas can precede MM in several species, and a cutaneous EMP has been reported to precede MM in a cat.10 This also has been reported occasionally in dogs and human beings.11,12

PATHOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

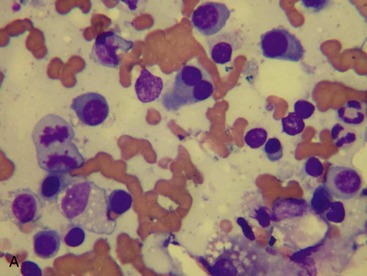

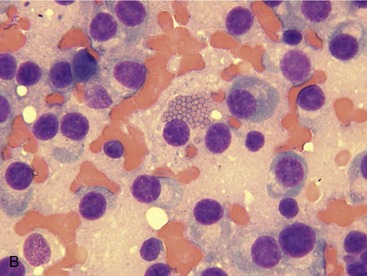

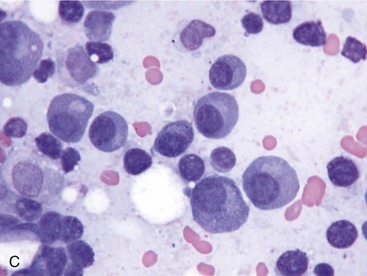

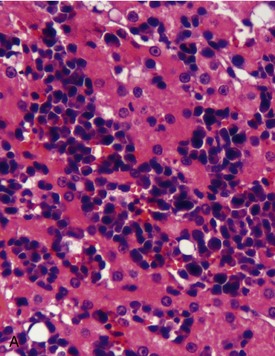

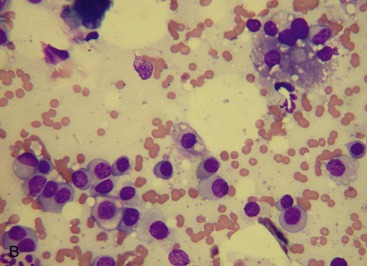

MM is derived from a clonal proliferation of malignant plasma cells (immunoglobulin-secreting B lymphocytes). It is a systemic disease arising typically from the bone marrow. The malignant plasma cells range from well differentiated to atypical on cytological and histological preparations. In a recent retrospective study, atypical cytological changes were noted in plasma cells in the majority of cats with MM. These changes included increased size, multiple nuclei, clefted nuclei, anisocytosis, anisokaryosis, variable N : C ratios, decreased chromatin density, and variably sized nucleoli.3 Flame cells, characterized by peripheral eosinophilic cytoplasmic projections, or Mott cells, characterized by Russell bodies representing globules of immunoglobulin, may be present (Figure 65-1).

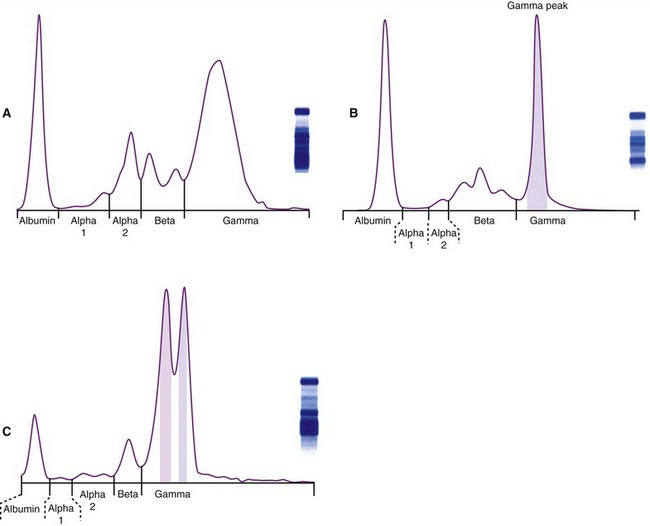

MM is characterized by the presence of a monoclonal gammopathy (M protein, M component, paraprotein) signifying the production of a single immunoglobulin from the neoplastic cells (Figure 65-2). In cats, this is represented most commonly by IgG gammopathy. The second most common M protein is IgA.3,13 Biclonal spikes also occur in cats, and this may be due to two independent secretory tumor cell lines each secreting a unique M protein, one tumor cell line producing two separate M proteins, or a spurious biclonal spike secondary to an increase in the dimeric protein IgA. A monoclonal increase in the pentamer IgM (Waldenström macroglobulinemia) has been reported in one cat.14 Waldenström macroglobulinemia in human beings is characterized by the absence of skeletal lytic lesions and the involvement of liver, spleen, and/or lymph nodes; more recently, it has been classified as a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma in human beings.6 Production of the entire immunoglobulin is most common in cats; however, light chain myeloma has been reported in two cats, as well as in a dog.15–17

Light chain myeloma is characterized by the presence of light chains (L chains) in urine without a concurrent monoclonal gammopathy. Nonsecretory disease, characterized by marrow plasmacytosis and skeletal lytic lesions, occurs in dogs and human beings,18 although it has not been reported in cats. This manifestation typically carries a poor prognosis in human beings.6 In heavy chain disease, which is rare in human patients and has been reported in one dog, the M protein is characterized by an incomplete heavy chain, lacking a light chain.19 Cryoglobulinemia has been reported in one cat.20 This is characterized by the oversecretion of an M protein that is insoluble at low temperatures. Clinical signs associated with cryoglobulinemia result from precipitation of the cryoglobulin in small-diameter blood vessels and include purpura, cold intolerance, and ulceration and necrosis of the skin of distal extremities. To evaluate for cryoglobulins, blood must be collected and serum separated at 37° C to avoid precipitation of the protein in the clot. Plasma cell leukemia can be diagnosed as either primary, without a previous diagnosis of MM, or secondary, with concurrent myeloma or plasmacytoma. This is a rare disease that has been reported in one cat with a cutaneous extramedullary plasmacytoma that progressed to MM with secondary plasma cell leukemia.3,10

CLINICAL SIGNS AND MANIFESTATIONS

In the three most recent compilations of feline MM cases, the most common presenting clinical signs are nonspecific and consist of lethargy, decreased appetite, and weight loss.3,7,8 Other clinical signs and physical examination abnormalities include polyuria/polydipsia, vomiting, diarrhea, lameness or paresis/paralysis, central nervous system signs, fundic changes (retinal hemorrhages, retinal detachment), palpable hepatosplenomegaly, other evidence of bleeding (epistaxis, oral bleeding), and concurrent skin masses.

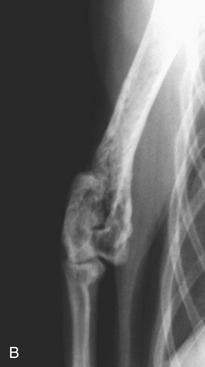

Bone lesions are characterized by lysis and are classically described as “punched-out” lesions (Figure 65-3). They can be single or multiple or represented by diffuse osteopenia or pathological fractures. Reported sites of skeletal lytic lesions are the pelvis, ribs, vertebrae, and long bones. Reports of the frequency of bone lesions in cats with MM are conflicting, ranging from 8 to 60 per cent.3,7,8

Extramedullary infiltration by neoplastic plasma cells is a common finding in feline MM. By contrast, extramedullary involvement is uncommon in human beings and dogs with MM.4,6 A recent report examining cats diagnosed with MM reported that approximately 40 per cent had cytologically or histologically confirmed plasma cell neoplasia in the spleen, liver, and abdominal lymph nodes, with splenic infiltration being the most common (Figure 65-4).3 Additionally, in a report evaluating the spectrum of myeloma-related disorders in cats, 50 per cent of cats with plasma cell infiltration in the bone marrow had concurrent involvement of abdominal organs. Several cats in this report had abdominal organ involvement without concurrent bone marrow infiltration. However, all of these cats had concurrent monoclonal gammopathy.8

Hyperviscosity syndrome (HVS) results from elevations in circulating M protein leading to increased serum viscosity. Incidence is highest with IgM due to the high molecular weight of IgM, a pentamer, followed by IgA, a dimer that can polymerize, and IgG. HVS also may be more common with cryoglobulinemia. High serum viscosity can lead to central nervous system abnormalities, such as mentation changes and seizures. It also can lead to increased cardiac workload and cardiac failure, retinal hemorrhages, and coagulation abnormalities. These complications are thought to occur secondary to sludging of blood in small vessels and ineffective delivery of oxygen to tissues.21,22 HVS was present in 40 per cent (four of nine) of cats in one study; however, serum viscosity is not measured routinely at most institutions.7

Bleeding diathesis or coagulation defects can result from several mechanisms, including M protein interfering with clotting factors and platelets, the Fab fragment of the M protein binding to fibrin preventing its aggregation, or adsorption of minor clotting proteins. Additionally, bone marrow infiltration (myelophthisis) may lead to thrombocytopenia.4,6 Evidence of bleeding diathesis or bleeding abnormalities was noted in approximately 30 per cent of cats in recent reports.3,7,8

Chronic kidney disease may be present for a variety of reasons in cats with MM. In three recent reports of MM in cats, 25 to 40 per cent of cats were azotemic.3,7,8 Light chain proteinuria occurs due to an unbalanced production of kappa (κ) or lambda (λ) light chains. These excessive light chains are filtered freely by the glomerulus leading to their presence in urine. Filtered light chains can form protein precipitates that lead to tubular damage and resulting azotemia. Other possible mechanisms of kidney disease include hypercalcemia, amyloidosis, renal infiltration by neoplastic plasma cells, decreased renal perfusion secondary to HVS, or pyelonephritis.4,6 Light chain proteinuria was reported in 40 to 50 per cent of cats with MM in recent reports.3,7 Amyloidosis, the systemic deposition of light-chain (AL) amyloid in organs (including the kidney), is rare in cats with MM.

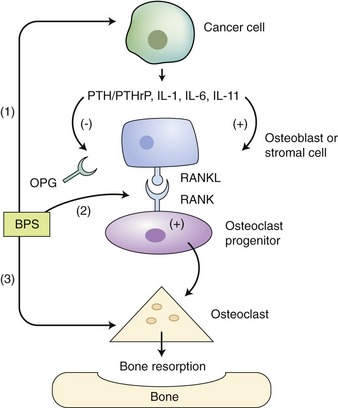

Hypercalcemia may result from direct tumor lysis of infiltrated bone or osteoclast activation. Osteoblast inhibition also is cited as a mechanism of hypercalcemia in affected human beings. In human patients, osteoclast activation occurs secondary to aberrant production of interleukin (IL)-1β (previously called osteoclast activating factor), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-β, and IL-6. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) also is elicited by parathyroid hormone (PTH), PTHrp, and IL-1β, and likely plays a role in hypercalcemia associated with MM. RANK (the receptor for RANKL) is located on osteoclasts and becomes activated with the binding of RANKL on stromal cells, osteoblasts, and possibly tumor cells (Figure 65-5).6,23 Hypercalcemia is reported to occur in 20 to 40 per cent of cats in recent reports.3,7

A number of factors contribute to the increased risk of infection in MM patients. In human beings with MM, there are documented decreases in the levels of uninvolved immunoglobulins, which increases patients’ risk for bacterial infections. Additionally, B-cell and T-cell function may be dysregulated secondary to immunosuppressive cytokines (e.g., TGF-β), and neutropenia may result from myelophthisis.6 One recent report includes three cats (approximately 20 per cent of the study group) with concurrent infectious processes, including upper respiratory infection, severe dental disease, and terminal bacteremia3; however, overwhelming infection is not reported commonly in feline MM patients.

Cytopenias were relatively common in recent reports, with approximately 55 to 75 per cent of cats being anemic, 30 per cent being neutropenic, and 50 per cent being thrombocytopenic. Anemia in cats with MM typically is nonregenerative, normochromic, and normocytic.3,6

Clinical signs and clinicopathological abnormalities in cats with MM reported since 2000 are summarized in Tables 65-3 and 65-4.

Table 65-3 Clinical Signs in Cats with Multiple Myeloma*

| Clinical Sign or Finding | Approximate Percentage |

|---|---|

| Anorexia | 70 |

| Lethargy | 65 |

| Bleeding abnormalities/evidence of bleeding diathesis | 30 |

| Lameness/hindlimb ataxia/weakness | 30 |

| Palpable abdominal organomegaly/mass | 25 |

| Vomiting/diarrhea | 25 |

| Polydipsia/polyuria | 20 |

| Neurological disease | 15 |

| Skin masses† | 10 |

N = 52.

* References 3, 7, 8, 10, 13, 19, 23.

† Mellor et al included cats with “myeloma-related disorders.” Five cats with solitary cutaneous plasma cell tumors with no systemic involvement were excluded from this summary.

Table 65-4 Clinicopathological Abnormalities in Cats with Multiple Myeloma*

| Abnormality | Approximate Percentage |

|---|---|

| M-protein | 100 |

| Monoclonal | 80 |

| Biclonal/polyclonal | 20 |

| Anemia | 60 |

| Bence Jones proteinuria | 40 |

| Azotemia | 40 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 40 |

| Neutropenia | 30 |

| Hypercalcemia | 25 |

| FeLV/FIV seropositive | 0 |

N = 28.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree