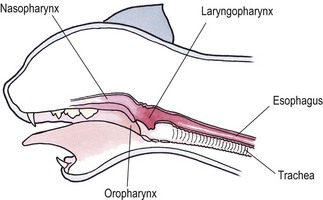

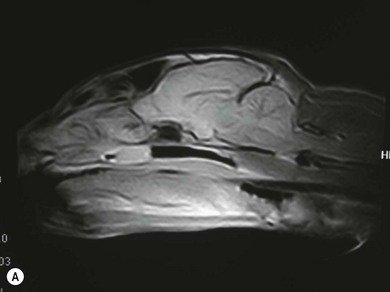

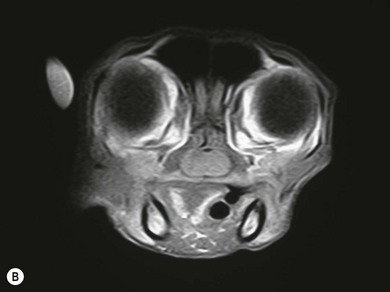

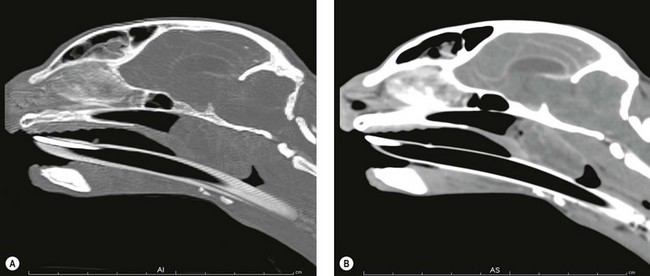

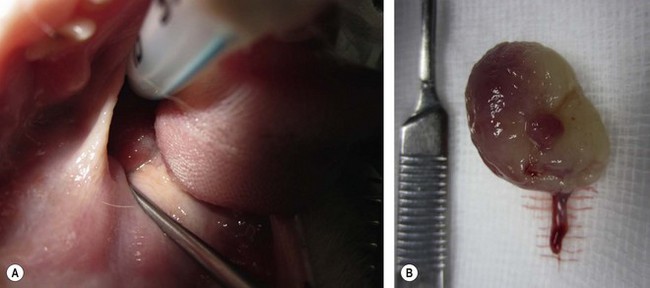

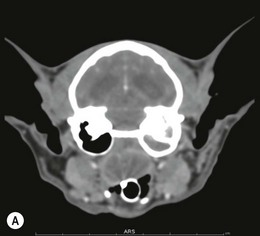

Chapter 51 The pharynx is a small anatomic region that is often forgotten or overlooked compared to the adjacent nasal passages, oropharynx, and oral cavity. However, a variety of clinical conditions relating to the nasopharynx have been described, comprising infectious (viral, bacterial, and fungal), inflammatory and neoplastic etiologies, along with anatomic abnormalities and foreign bodies.1 In cats with nasopharyngeal mass lesions, the most common inflammatory causes are polyps and cryptococcosis, and the most common neoplastic cause is lymphoma.2 Surgical intervention for disorders of the nasopharynx is not commonly performed, with the exception of nasopharyngeal polyps, stenosis and, occasionally, foreign bodies. The pharynx comprises the caudal aspects of the oral and nasal cavities at the confluence of the digestive and respiratory tracts. The pharynx is a short fibromuscular tube divided into three compartments: the oropharynx, the nasopharynx and the laryngopharynx (Fig. 51-1). Surgical diseases of the oral cavity are described in Chapter 49, the ear in Chapter 50, the larynx in Chapter 52, and the nasal cavity is described in Chapter 54. This chapter will deal primarily with the nasopharynx, as many oropharyngeal disorders also affect the oral cavity. However, the pharynx is a common space and diseases of the nasopharynx may affect all parts of the pharynx. Extension of nasal cavity disease into the nasopharynx and vice versa is relatively common and the chapters dealing with these diseases should be read in conjunction. The clinical signs of nasopharyngeal disease are stertor, open-mouth breathing (Fig. 51-2), repeated attempts at swallowing, nasal discharge, and reverse sneezing. The clinical signs of oropharyngeal or laryngopharyngeal disease are pain, anorexia, dysphagia, and stridor. Figure 51-2 A middle-aged cat was presented with open-mouth breathing associated with an obstructive pharyngeal mass. Cats with nasal disease more commonly have a history of nasal discharge and sneezing, whereas cats with nasopharyngeal disease more commonly have stertorous respiration, change in phonation, and weight loss,3 although nasal discharge and sneezing may still be present. In a compliant animal, the soft palate may be palpated and pushed dorsally to identify nasopharyngeal mass lesions, although only a brief examination will be possible. For a right-handed operator, the cat’s head is supported in the left hand, with the index finger and fourth finger on either side of the temporomandibular junction, with the palm supporting the head. The mouth is then opened using pressure from the middle finger on the mandible and then the right index finger is introduced into the mouth to palpate the soft palate.3 The effect of opening the mouth on the nature of any respiratory noises is assessed. Physical examination of the conscious animal is followed by examination of the pharynx under a light plane of anesthetic (Fig. 51-3). Anesthesia should be induced with an intravenous agent so that rapid induction and rapid intubation and control of the airway can be achieved in patients with an obstructive lesion. Use of an intravenous agent also allows anesthesia to be maintained without the presence of an endotracheal tube if a more detailed examination of the pharynx is required without an endotracheal tube in place. The endotracheal tube cuff should be inflated, and the caudal pharynx should be packed with gauze if this does not impair the examination, to prevent aspiration of blood or other fluids. The pharynx is a very sensitive area and manipulations may cause the animal to wake up. To avoid having a very deep plane of anesthesia, a local anesthetic technique, such as topical administration of lidocaine trickled from the external nares or direct administration to the pharyngeal mucosa may be used. This may also avoid excessive vagal stimulation from intrapharyngeal manipulation, which may cause a clinically significant bradycardia. Once the animal is anesthetized, it may be placed in dorsal recumbency and a more detailed examination of the pharynx can be performed. Palpation of the soft palate, followed by rostral retraction with an instrument, e.g., a spay hook, is performed (Fig. 51-4). In cats, the cranial nasopharynx and choanae may be exposed in this manner. In one series of 53 cats with nasopharyngeal disease, 23 cats (43.4%) had soft palate palpation performed and in 82% of these a palpable mass was identified.3 Palpation is of limited value for masses located dorsal to the hard palate, but diagnostic imaging or endoscopy (see Chapter 9) will identify these.3 Figure 51-4 Spay hooks have been used to retract the soft palate rostrally in this anesthetized cat with a nasopharyngeal polyp. Visualization of the nasopharynx is achieved by retrograde rhinoscopy (see Chapter 9) with an endoscope passed into the oral cavity and retroflexed 180°. A limited examination of the nasopharynx may be achieved with a dental mirror and a light source and the soft palate may be retracted with a tissue hook or stay suture to increase visibility. On endoscopy, mass lesions may be visualized, although in some cases visualization is obscured by pus, blood or mucus. Flushing of the site with saline, either via the endoscope or via the external nares, may clear the field and improve visualization. In one study of endoscopic examination of the choanae in 27 cats with signs of upper respiratory tract disease, gross abnormalities were identified in 85% of the cats, with a mass (44%), rhinitis (25%), foreign bodies (7%), follicles (3.5%), and deformed choanae (3.5%) being noted.4 A technique to perform nasopharyngoscopy via gastrotomy has been described that allows the use of a larger endoscope which does not have to be retroflexed, but since this involves an additional surgical approach it is not recommended unless there is no alternative method of examination.5 However, this method does allow larger diameter instruments to be used and has been successful in removing a large (3.5 cm long) polyp.5 The caudal nasal cavity and rostral nasopharynx may be examined with a rigid (2–4 mm) arthroscope or flexible endoscope passed via the external nares. If anterior rhinoscopy is also required, it is performed after retrograde pharyngoscopy to avoid causing hemorrhage that might obscure the view.4 Radiographs should include the nasal and oral cavity rostrally and the proximal trachea caudally, and should be taken at inspiration to increase the volume of gas in the pharynx. The high inherent contrast of this area allows delineation of the nasopharynx, oropharynx and laryngopharynx, and soft palate. Examination of the nasopharynx is impaired by superimposition of the bones of the skull and the presence of the endotracheal tube and other anesthetic monitoring devices. If evaluation of the external ear canal and tympanic bullae is required, additional projections are needed. Masses, radiopaque foreign bodies (Fig. 51-5), and secretions may be identified with radiography, but apart from these lesions, radiography may offer little more information than a thorough endoscopic examination. In animals where swallowing is impaired, or in whom the clinical signs are suggestive of this, radiographs of the thorax should be taken to rule out aspiration pneumonia and megaesophagus. Figure 51-5 A cat with a history of nasal discharge. (A) Lateral and (B) dorsoventral radiographs of the skull show a radiopaque metallic foreign body in nasopharyngeal meatus that was found to be a bell. The foreign body was removed by flushing from the external nares. Contrast radiographs following administration of contrast medium via the ventral nasal meatus may aid in the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal disease, e.g., stenosis.6 Fluoroscopy is of theoretical use in the evaluation of animals with dysphagia, but these examinations are very difficult to perform in cats. Ultrasonography may be of use for soft tissue or fluid-filled masses encroaching on the pharynx, or assessment of the retropharyngeal lymph node, and may guide sampling of these areas. Computed tomography (CT), with and without contrast, is the most useful modality for evaluating the nasopharynx (Fig. 51-6) and allows investigation of the status of the regional lymph nodes. Both bone and soft tissue windows should be evaluated and it is important to differentiate between a soft tissue mass and mucus in the pharynx.3 The nasal passages, external ear canals, and tympanic bullae should be assessed at the same time. Fluid within the tympanic bullae may be seen in animals with nasopharyngeal masses, most likely due to obstruction of the pharyngeal opening of the auditory tube.7,8 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination may allow a better appreciation of the relationship of a soft tissue mass to the surrounding soft tissues of the nasopharynx6 (Fig. 51-7) and is the imaging modality of choice if intracranial extension of a mass is suspected.7 Figure 51-6 A cat with a history of inspiratory stertor. CT image of the head reconstructed in the sagittal plane post-contrast administration showing a large heterogeneously enhancing nasopharyngeal mass. (A) Bone window (width 2000, level 350). (B) Soft tissue window (width 400, level 40). Diagnosis may require biopsy of a lesion, particularly masses that do not have the gross appearance of a nasopharyngeal polyp. Fine needle aspirates or Tru-Cut biopsies may be taken under direct visualization, taking care to avoid the large blood vessels that lie lateral to the pharynx. Anterograde flushing of the nasopharynx from the external nares may also allow pieces of tissue or foreign bodies to be recovered, as well as producing temporary alleviation of clinical signs in animals where obstruction is due to a friable mass or thick fluid. In animals presenting with clinical signs consistent with nasal or nasopharyngeal disease, direct visualization of the nasopharynx and biopsy of any lesions is a simple, inexpensive technique with a high diagnostic yield and is preferred to biopsies achieved via rhinoscopy.3 In one study of 38 cats with endoscopically detected nasopharyngeal masses, a histologic sample of diagnostic quality was obtained in 34 of them (89%).9 Forty per cent of these cats also had a co-existent nasal mass. In another study of 27 cats with signs of upper respiratory tract disease, histologic or cytologic samples were retrieved in 18 animals.4 Diagnoses included neoplasia (nine cats), rhinitis/hyperplasia (seven cats), polyp (one cat) and cryptococcosis (one cat). In cats with a mass lesion at the choanae, the diagnosis was neoplasia in 58%, polyp in 18%, rhinitis in 18%, and unknown in 9%. Thick tenacious mucus may also appear as a mass lesion.8 In 30 cats with nasopharyngeal masses, squash preparation cytology showed a good agreement (90%) with histology, although the agreement was poorest for lymphoid lesions.9 The histologic diagnoses were benign inflammatory/hyperplastic lesions (11 cats), lymphoma (12 cats), carcinoma (five cats), and sarcoma (two cats). Nasopharyngeal polyps are the most commonly described entity, but this disorder may not be the most common disease. In a review of 53 cats with nasopharyngeal disease, the most common diagnosis was lymphoma in 49% of cats, with nasopharyngeal polyps being reported in 28%. The remaining 23% of cats had other tumors including squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and lymphoplasmacytic rhinitis/pharyngitis.3 The mean age at presentation aids in prioritizing the differential diagnosis list—cats with nasopharyngeal polyps have a mean age of three years (range four months to seven years) and those with lymphoma are 10.7 years (range five–19 years). Nasopharyngeal polyp is the name given to a benign proliferation arising from the respiratory epithelium that may be found in the nasopharynx. The most common type of polyp originates in the middle ear or auditory tube and extends via the auditory tube into the nasopharynx (Fig. 51-8). In this location the polyp may grow to a large size (>3 cm). A middle ear polyp is the name given to a polyp that originates in the middle ear and/or Eustachian tube and grows through the tympanic membrane into the external ear canal, although the term nasopharyngeal polyp is often used to refer to both these entities. The middle ear mucosa may be diffusely inflamed with a polypoid lining. These may occasionally be bilateral, either at the same time or sequentially.10,11 In some cats, polyp tissue may be present in both locations.10,12 Inflammatory polyps of the nasal turbinates (IPNT) that may extend into the nasopharynx have also been described as a distinct entity.13–15 These have been reported to be more common in Italy14 than other European countries. Figure 51-8 A cat with a history of inspiratory stertor. (A) A spay hook has been used to retract the soft palate rostrally and visualize a large nasopharyngeal polyp. (B) The polyp was removed by gentle traction and the typical stalk can be seen. The cause of the polyps is unknown, although it has been proposed that they originate from a congenital defect (e.g., remnants of the branchial arches16) or middle ear disease,17 or as a result of chronic inflammation, infectious or otherwise, which may either initiate or potentiate the growth of the polyp. Soft palate hypoplasia was reported in one cat with a nasopharyngeal polyp.18 The polyps are associated with inflammation and are often secondary to bacterial infection, although it is not clear whether the polyp causes the inflammation or the inflammation causes the proliferation of the mucosa. Feline calicivirus, which is an infectious agent known to colonize cats, has been isolated from the nasopharynx of cats with polyps and from an inflammatory polyp in one cat.19 However, other studies have not consistently amplified RNA or DNA of infectious agents, including feline herpesvirus-1 (FHV-1), feline calicivirus (FCV), Mycoplasma species, Bartonella species, and Chlamydophila felis from polyp tissue and there was no difference in the amplification rates in normal and affected cats.11,20 In addition, a previous history of recent upper respiratory tract infection is not commonly reported in cats with polyps.11 Most affected cats are young adults, although polyps have been reported in older cats up to 15 years old. Clinical signs are referable to an obstructive lesion at the level of the nasopharynx or disease of the middle ear or external ear canal. Inspiratory dyspnea and stertor are the primary signs, but dysphagia, gagging or reluctance to eat may also be seen. Occasionally, polyps may cause life-threatening upper airway obstruction, either with normal activity21 or on recovery from anesthesia if a polyp is not suspected and diagnosed.19,20 Acquired megaesophagus has also been reported,10,22 which resolves on removal of the polyp. In one cat this was associated with a large (7 cm long) nasopharyngeal polyp that extended into the cranial esophagus.22 Pulmonary hypertension, presumed to be due to chronic upper airway obstruction, is reported in one cat.10 Clinical signs of nasal cavity disease, i.e., sneezing and nasal discharge, are generally uncommon, unless secondary infection extends from the nasopharynx to the nasal cavity. However, similar polyps may also be found in the nasal cavities, and clinical signs of nasal cavity disease such as sneezing, epistaxis, and stertor may be seen with polyps in this location.13,14 A middle ear polyp is the most common mass identified in the external ear canal in the cat. In most cats, the polyp does not extend beyond the horizontal canal, but in some cats it may be visible in the external ear canal. Middle ear polyps may cause signs of otitis externa (e.g., head shaking, scratching at the ear, and aural discharge) or otitis media/interna (e.g., Horner syndrome [Fig. 51-9], head tilt, ataxia, and nystagmus). Figure 51-9 A cat with a nasopharyngeal polyp and associated middle ear disease with right-sided Horner syndrome, showing miosis, ptosis, and enophthalmus. Examination of the oral cavity may reveal ventral depression of the soft palate and resistance to gentle dorsal pressure on the soft palate. Less than half of affected cats have a visible mass on physical examination.23 Rostral retraction of the soft palate may improve visualization of smaller or more rostral lesions. Large lesions may obstruct the larynx and may cause difficulty on endotracheal intubation. Radiography or CT examination will reveal a soft tissue mass in the nasopharynx, which may depress the soft palate ventrally. More than 80% of cats have evidence of middle ear disease on diagnostic imaging (Figs 51-10 and 51-11).24 Figure 51-10 A cat with a history of inspiratory stertor and otitis media/interna due to a nasopharyngeal polyp. (A) Transverse plane and (B) dorsal plane reconstruction CT images of the head show sclerosis and thickening of the left tympanic bulla, filling of the bulla with hyperattenuating material, and a large hyperattenuating nasopharyngeal mass with a rim of contrast enhancement.

Pharynx

Surgical anatomy

General considerations

Clinical signs

Physical examination

Anesthesia

Endoscopy

Diagnostic imaging

Biopsy

Surgical diseases

Polyps

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pharynx