Chapter 21 PERIPARTURIENT DISEASES

NORMAL PERIPARTURIENT CONDITION OF THE BITCH

Blood and Serum

Decreases in red blood cell numbers during pregnancy are expected, with hematocrits as low as 30% to 35%. Serum cholesterol concentrations may increase during pregnancy whereas the total serum protein, albumin, and calcium concentrations decrease (Bebiak et al, 1987). Total serum thyroxine (T4) concentrations increase during pregnancy (Reimers et al, 1984), as do the activities of coagulation factors VII, VIII, IX, and XI (Olson, 1988). Some breeds may have unique alterations. Knowing what is expected for bitches and their specific breeds can be important when determining whether a bitch is in need of medical assistance.

CLINICAL PSEUDOPREGNANCY (PSEUDOCYESIS)

Definition and Signs

All normal bitches enter a luteal phase (diestrus) of progesterone dominance following estrus (standing heat). Progesterone assays do not demonstrate any clear biochemical distinction between nonpregnant and pregnant bitches. Physiologically, all nonpregnant bitches in diestrus are pseudopregnant. However, this reference to a normal physiologic process needs to be differentiated from clinical pseudopregnancy, a syndrome recognized by breeders and veterinarians.

Less commonly, the signs may be quite overt and confusing, such as lactation or abdominal contractions. Certainly, some of these signs in a diestrual bitch would make an owner suspicious that his or her dog is pregnant. Bitches have been examined for delayed parturition, uterine inertia, or dystocia that have subsequently been demonstrated to be pseudopregnant! The phenomenon of nonpregnant bitches lactating could have had functional importance in evolution, when nonbred mature bitches (such as the wolf) have had to nurse and tend the litter of the pack-leading she-wolf (Voith, 1980).

Physiology

Lactating pseudopregnant bitches are definitely under the influence of prolactin. However, prolactin secretion has been demonstrated to rise in bitches that do not lactate, suggesting that excessive concentrations or an increased sensitivity to prolactin may explain the clinical condition (Harvey, 1998). Therefore, the physiologic process that causes clinical pseudopregnancy is a composite of exquisitely timed normal hormonal fluctuations. There has been a suggestion that restricted food intake may decrease the incidence of pseudopregnancy in dogs, but this observation may not have clinical implications (Lawler et al, 1999). It is most important that owners understand pseudopregnancy is an exaggeration of normal.

Diagnosis/Interpretation

One differential diagnosis for galactorrhea is hypothyroidism. It has been suggested that increases in thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH) promotes prolactin secretion and then lactation. One dog has been described with hypothyroidism, increased serum prolactin concentration, and galactorrhea (Cortese et al, 1997).

Treatment

CONSERVATIVE THERAPY.

If these measures do not succeed or if a more aggressive strategy is deemed necessary, one or both of the following are helpful. We recommend that water be removed from the bitch for a 6- to 10-hour period each night for 3 to 7 nights. This water deprivation forces fluid conservation, and lactation quickly ceases. Alternatively, a bitch can be treated with furosemide (Lasix) at an oral dosage of 0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg TID until lactation ceases (usually less than 7 days). Water restriction should not be implemented if furosemide is used.

Light sedation with a tranquilizer for several days may be helpful. The use of phenothiazines has been discouraged in the management of pseudopregnancy because they may inhibit or antagonize dopamine, which is a prolactin-inhibiting factor; that is, they may stimulate synthesis and/or secretion of prolactin. Therefore other forms of sedative or tranquilization medication are recommended (Voith, 1983). An alternative to tranquilization is to exercise a bitch in an attempt to interrupt unwanted behavior.

AGGRESSIVE THERAPY.

Progesterone.

If conservative attempts at therapy are unsuccessful and lactation is persistent, alternatives may be considered. Progesterone administration (megestrol acetate, 2 mg/kg/day for 8 days) actually returns the bitch to a diestrus condition hormonally and usually alleviates signs of clinical pseudopregnancy. However, when progesterone administration is discontinued, there is a repetition of the same hormonal events that initially caused the signs. Thus lactation may recur as the effects of the progesterone dissipate and prolactin is secreted. This form of therapy is not recommended (Concannon and Lein, 1989).

Estrogen or Testosterone.

Estrogen therapy (diethylstilbestrol [DES], 1 mg/day orally for 7 days) may alleviate pseudopregnancy but also may cause signs of proestrus or estrus. Testosterone can be administered at a dose of 1 to 2 mg/kg intramuscularly. The androgen mibolerone (Cheque) has been moderately successful in reducing the physical and psychologic signs of pseudopregnancy. The dose recommended is 0.016 mg/kg orally, once daily, for 5 days (Brown, 1984). However, fewer than 50% of the 63 dogs with physical evidence of pseudopregnancy responded. The response seen in bitches with psychologic problems associated with pseudopregnancy was better.

Prolactin Inhibitors.

Ergot alkaloids (ergolines) and their derivatives have been identified as potent prolactin inhibitors (Krulich et al, 1981; Ferrari et al, 1982). They act via direct dopamine receptor stimulation at the level of the pituitary gland. Bromocriptine, an ergoline compound and dopamine agonist, inhibits pituitary secretion of prolactin. Bromocriptine, administered orally at 0.01 to 0.1 mg/kg/day in divided doses, does inhibit lactation and should be given until lactation ceases (Mialot et al, 1981, 1982; Janssens, 1986). Side effects to bromocriptine are common and include vomiting, anorexia, depression, and behavioral changes (Peterson and Drucker, 1981). Vomiting can be reduced by administering an antiemetic drug at the time bromocriptine is given. This is our drug of choice if aggressive treatment of a bitch is necessary; however, we have never needed to use it.

An equally effective but better-tolerated ergoline compound (cabergoline) was identified and evaluated. Cabergoline, administered at a dose of 5 μg/kg once daily for 5 to 10 days, was effective at sharply dropping prolactin concentrations and suppressing lactation in more than 95% of the bitches treated (Di Salle et al, 1984; Jochle et al, 1987; Arbeiter et al 1988). Side effects were considered mild and included lethargy (25% of dogs), inappetence, and vomiting (<5% of dogs). Success was slightly lower (21 of 26 dogs) in a more recent study (Harvey et al, 1997). Furthermore, the conclusion of the most recent study was that cabergoline is effective in suppressing prolactin release from the pituitary gland, but that this suppression may only be transient.

The drug has also been used to induce abortion in the second half of pregnancy in the bitch (Post et al, 1988). In a comparison between cabergoline and bromocriptine use in women, cabergoline was more effective and better-tolerated when used for hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea (Webster et al, 1994).

Ovariohysterectomy.

Ovariohysterectomy (OVH), also referred to as spaying, is the one therapy that should not be considered or recommended in any pseudopregnant dog. The procedure may exacerbate the syndrome by eliminating progesterone from the system and further stimulate prolactin secretion. On rare occasions, OVH may result in prolonged signs. In fact, because of this concern, some authors recommend avoiding OVH until a period of 4 to 5 months after the previous heat has passed (Harvey, 1998).

Pseudopregnancy-Induced Disorders and Incidence of Recurrence

No association appears to exist between clinical pseudopregnancy and the development of infertility, pyometra, poor mothering/nursing habits, or any other disorder. Clinical pseudopregnancy is simply an exaggeration of a normal state. If the owners of a bitch are distressed by repeated bouts of clinical pseudopregnancy, they should attempt to have the bitch become pregnant or consider ovariohysterectomy. (If repeated attempts at breeding have not been successful, consult the section Infertility of the Bitch and Associated Breeding Disorders.) Some dogs exhibit clinical pseudopregnancy after every heat. OVH should be strongly advised if breeding is not planned (Harvey, 1998).

EXTRAUTERINE FETUSES

Although extremely rare, it is possible for a dog to have fetuses develop outside the uterus. This could happen following a uterine tear that occurred during pregnancy, which would allow exteriorization of fetuses. The tear could be the result of external trauma to the uterus, or death of a fetus could cause local necrosis of the uterine wall. Clinical signs may be absent or a bitch may have vague signs of illness during pregnancy or following parturition. Definitive diagnosis would most likely be made with ultrasonography or at surgery (Shamir and Shahar, 1996).

SPONTANEOUS ABORTION AND RESORPTION OF FETUSES

Incidence

Premature expulsion of dead or living fetuses during late gestation (abortion) or resorption of a fetus or fetuses poses a difficult diagnostic dilemma for veterinarians. The incidence of abortion or resorption of canine fetuses is extremely difficult to assess, because no reliable method is available to confirm pregnancy during the first 3 weeks of gestation and because most bitches are never evaluated with abdominal ultrasonography or radiography until a problem develops. Many bitches thought to have aborted or resorbed a litter were likely never pregnant. Furthermore, bitches may consume or bury aborted fetuses, making it more difficult to confirm a diagnosis. However, a recent ultrasound study demonstrated that resorption of one or two conceptuses occurs in up to 10% of pregnancies (England, 1998).

Causes

GENERAL.

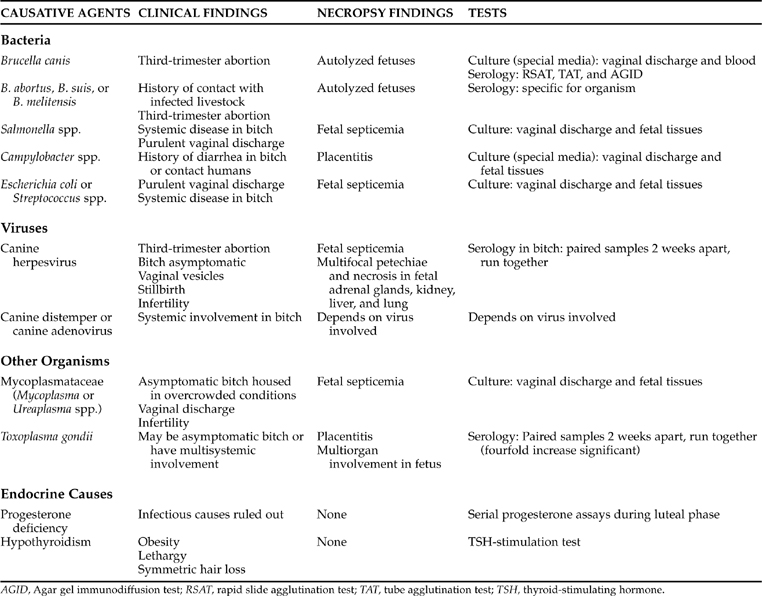

A myriad of causes exists for any bitch to abort all or part of a litter. Even when aborted fetuses and/or placentas are evaluated histologically, the exact cause for pregnancy failure may not be understood. The causes of pregnancy failure can encompass congenital/hereditary defects; infectious causes; exposure to drugs, toxins, or trauma during pregnancy; uterine disease; hormonal abnormalities; severe malnutrition; and significant systemic illness. In general terms, these causes are categorized into fetal defects, abnormal maternal environment, and infectious agents (Table 21-1).

ABNORMAL MATERNAL ENVIRONMENT.

Systemic Disease.

Any factor causing significant stress or damage to the uterus or fetus can cause fetal death. Included among these problems is any serious disease within or outside the reproductive tract. For example, a bitch that develops severe cardiac disease during pregnancy is likely to have a compromised uterine blood supply, leading to fetal death. Similar problems can arise with any major organ disease. Hypothyroidism has been included as a potential cause for abortion. The veterinarian must remember that a bitch ill from any significant systemic illness may be euthyroid but have thyroid function test results consistent with hypothyroidism (euthyroid sick syndrome; see Chapter 3). Diabetes mellitus, perhaps the most common endocrine disease in dogs, is definitely associated with an inability to carry a litter to term and abortion. All female dogs with diabetes should undergo OVH.

Hypoluteoidism.

Pregnancy is maintained by progesterone derived from ovarian corpora lutea. Failure to maintain progesterone concentrations above a critical level (1.0 to 2.0 ng/ml) is likely to result in expulsion of the fetus. A luteal phase defect has been associated with pregnancy failure in women, but the diagnosis is considered controversial (Meis et al, 2003). The syndrome has not been well documented in dogs (Olson, 1988), although one case has been described (Purswell, 1991). Progesterone insufficiency is possible, and progesterone concentrations may be low at the time of an abortion. The decreases, however, may be secondary to fetal death rather than representing the primary cause. It has been demonstrated that fetal death will result, within days, in subsequent decreases in serum progesterone concentration (Concannon et al, 1990). Furthermore, fetal distress secondary to virtually any cause may result in decreased serum progesterone concentrations (Johnston et al, 2001). Subnormal progesterone concentrations in a bitch that has already aborted is not proof of hypoluteoidism.

It is accepted that serum progesterone concentrations must be in excess of 2 ng/ml for maintenance of pregnancy. However, such concentrations are at the detection limits of ELISA kits, which usually estimate concentrations as less than 1 ng/ml, 1 to 5 ng/ml, and greater than 5 ng/ml. Precise determination of progesterone concentration is critical in the diagnosis. The veterinarian cannot be completely confident using in-hospital assay systems. The bitch described in the Purswell report may not have had hypoluteoidism, because the laboratory progesterone value at the time of diagnosis with the kit was rechecked and documented to be 6.5 ng/ml (Purswell, 1991). One value should be considered inadequate to confirm a diagnosis. Laboratory progesterone concentrations should be used to confirm or deny borderline results. Does the syndrome exist? Possibly.

If treatment is attempted for hypoluteoidism, several strategies can be employed. It is important to know the first day of diestrus, as defined with vaginal cytology (see Chapter 19). Exogenous progesterone should be discontinued after 50 to 53 days of diestrus (whelping typically occurs 55 to 58 days into diestrus). A recent study demonstrated that 3 mg/kg of progesterone in oil, intramuscularly, once daily (Progesterone Injection; Steris Laboratories Inc, Phoenix, AZ) is adequate to maintain serum concentrations above 10 ng/ml. Serum progesterone concentrations decreased below 2 ng/ml 48 to 72 hours after the final injection (Scott-Moncrieff et al, 1990). As little as 2 mg/kg every 48 hours may be sufficient to maintain pregnancy (Eilts, 1992). Alternatively, synthetic progesterone (17α-ethyl-19-nor-testosterone [Steraloids Inc, Denville, NJ]), 1 mg/kg SC daily, has been used successfully in maintaining pregnancy in ovariectomized bitches (Steinetz et al, 1989). The use of Ovaban (Schering, Union City, NJ) for preventing hypoluteoidism has not been described, although undocumented reports of 5 mg/day until day 55 of diestrus have been suggested.

An oral progestogen, allytrenbolone (Regumate, Hoechst RA), has been evaluated for maintaining pregnancy in ovariectomized bitches. Bitches were treated following ovariectomy on day 30 to 32 of pregnancy. Treatment was continued through day 54 of cytologic diestrus. The use of 0.044 mg/kg daily maintained pregnancy in only two of six pregnant bitches. The use of 0.088 mg/kg (0.2 cc/10 pounds) resulted in three of three bitches carrying their litters to term, with parturition beginning on the expected date in each. However, although two bitches had normal parturition, one had dystocia and death of all puppies. None of the bitches receiving the Regumate at either dosage had optimal milk production. Several litters were said to have been nursed by untreated controls, one bitch was able to nurse most of her litter 3 days after whelping, and one was able to nurse her entire litter beginning 3 days after whelping. Prolactin secretion was assumed to be suppressed by the drug in all bitches. If use of the drug is contemplated, clients must be warned that milk supplementation may be needed. In addition, the drug should not be used unless whelping dates have been reliably estimated, with serial progesterone concentrations obtained during proestrus and early estrus or with vaginal smears used for identifying day one of diestrus (Eilts, 1992).

INFECTIOUS AGENTS.

Numerous agents have been implicated in causing uterine infection, fetal death, and resorption or expulsion of litters from the bitch (see Table 21-1). These agents include Brucella, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus, herpesvirus, canine parvovirus, distemper virus, mycoplasma, Campylobacter species, Toxoplasma, and others. In our experience, confirming that a litter has been lost and that the cause was an infectious agent is quite difficult. If infection is to be pursued, it is recommended that fetal/placental or neonatal tissue, stomach and stomach contents, and vaginal swabs of the bitch be submitted for culture. Infectious agents, such as Campylobacter, may require special handling (Bulgin et al, 1984).

Canine Herpesvirus Infection.

CHV infection in neonatal pups is an acute fatal infectious disease characterized by generalized focal necrosis and hemorrhage. The disease in adult dogs is usually subclinical or mild, such as conjunctivitis, serous or mucopurulent ocular and/or nasal discharges, and vaginal/vestibular/vulvar lesions that are vesicular early in the course of the disease and later become circular and pock-like. Genital lesions usually disappear shortly after infection, but they may reappear with the onset of proestrus. Canine herpes virus infection can result in fetal resorption and/or mummification if the bitch is infected early in gestation, abortion if the bitch is infected in mid-gestation, or premature birth if infection occurs in late pregnancy (England, 1998). A bitch may have dead and/or mummified fetuses in the same litter with unaffected live pups. Abortion has occurred between 44 to 51 days of gestation following infection on day 30. It is also possible for an infected bitch to be infertile or to have litters that are small in number. The fetal placenta from a bitch with canine herpesvirus infection is typically underdeveloped and congested. Several grayish white foci ranging in size from miliary to “rice grain” in size can be observed in the placental labyrinth. Sometimes the lesions form zonal structures 2 to 3 mm wide. Typical changes are also seen histologically.

Transmission of herpesvirus can occur venereally, transplacentally, via fetal contact with virus-filled vesicles that rupture during birth, or through respiratory routes of infection. Diagnosis depends on viral isolation. Viral isolation requires fastidious sampling and culture techniques from refrigerated but not frozen tissue. A negative culture for this virus may be due to inadequate methodology. Separation of infected animals from noninfected animals is advisable, especially in the final 3 weeks of gestation and the first 3 weeks of life. Because no vaccine is available for prevention, veterinarians can only recommend careful physical examination and review of the history from dogs to be used in a breeding program (Hashimoto and Hirai, 1986; Evermann, 1989).

Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma Infections.

These microorganisms are among the recognized normal flora in the canine vagina. Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma isolates have been implicated in infertility, early embryonic death/resorption, abortion, stillbirths, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Dogs may be exposed to large concentrations of these organisms in crowded kennel conditions. Diagnosis is always tentative at best because positive vaginal cultures may simply include normal flora, and identifying the pathologic situation usually depends on demonstrating pure infection with one of these organisms in a bitch with metritis/vaginitis. Mycoplasma- or Ureaplasma-induced abortion is rare. Treatment involves the administration of chloramphenicol or tetracycline for 10 to 14 days. These antibiotics should not be given to neonates or to nursing bitches. The pregnant bitch can be treated with erythromycin, although this antibiotic is not as effective and it may result in gastrointestinal problems (Lein, 1986; Purswell, 1992).

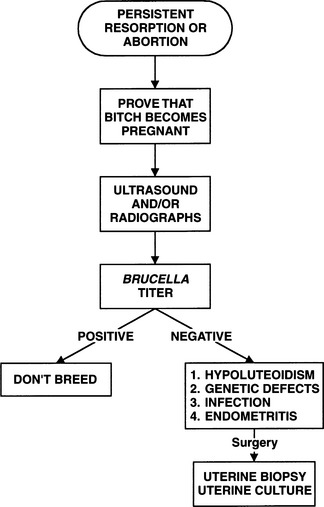

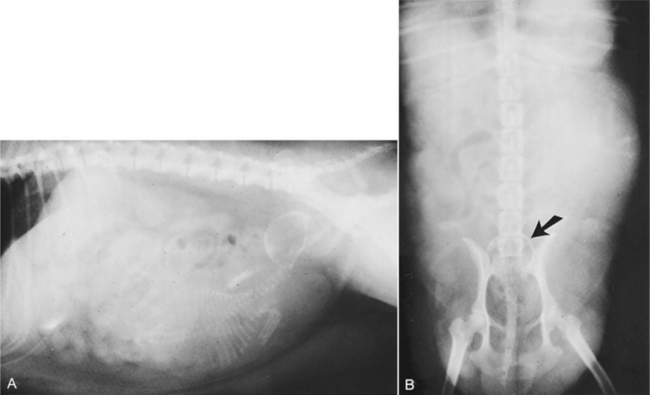

Diagnosis (Fig. 21-1)

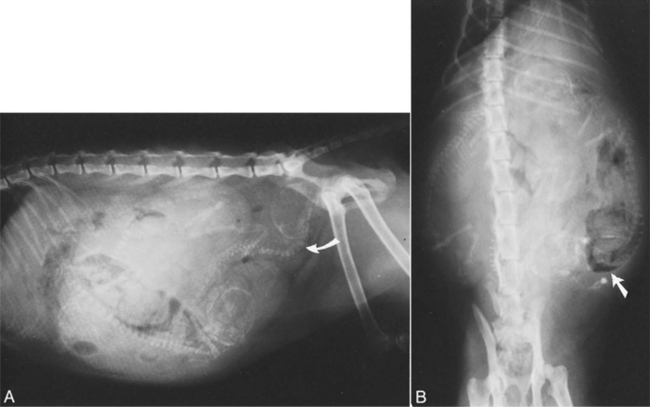

Abdominal radiography can also serve as a tool in recognition of pregnancy and, therefore, of abortion or resorption. This tool is not as reliable as abdominal ultrasonography because pregnancy cannot be confirmed radiographically until skeletal development is complete; after 42 to 45 days of gestation. Thereafter, collapse or decalcification of the skeleton, intrafetal gas, or an abnormal fetal position can be helpful in assessing viability of fetuses (Fig. 21-2).

If a pregnant bitch is brought to the clinic exhibiting signs consistent with illness or abortion, the veterinarian must focus on completing a thorough history and physical examination. The reproductive history should include the results of previous matings and any previous problems possibly related to the reproductive tract. A careful accounting of this breeding and information regarding the male is imperative. Results of Brucella testing of the bitch and dog, as well as previous mates, are critical. Additional information to obtain includes vaccination and worming protocols; travel, contact, or exposure data; diets and supplements; environmental conditions; and medications (see Chapter 20). The physical examination should include careful and gentle abdominal palpation. Vaginal examination must be performed and culture and cytology obtained. Radiography and/or ultrasonography should be strongly considered. Blood and urine tests can be chosen as dictated by the history and physical examination. Titers for the various infectious agents may be diagnostic. Hormone assay for progesterone concentrations may be helpful in determining the likelihood of ovarian failure during the course of pregnancy. Low plasma progesterone concentrations (<2 ng/ml) indicate that corpora luteal function has failed as a primary defect or secondary to some other disorder.

Treatment

THE BITCH THAT HAS ABORTED A LITTER.

The bitch that has a recent history of abortion and systemic illness should be evaluated for pyometra, retained or mummified fetuses, and/or retained placentas. Occasionally, palpation of the abdomen is sufficient to recognize these problems. The characteristics of any vaginal discharge may provide a clue in diagnosing ongoing uterine problems. A bitch with significant uterine infection rarely benefits from antibiotics alone. Prostaglandin therapy may be necessary if the owner wants to attempt future breeding (see pyometra, Chapter 23). Ovariohysterectomy may be considered if future breedings are not a priority.

The bitch that has aborted a litter but remains clinically healthy is easier to manage. A Brucella titer should be checked. If the bitch has aborted only once, she simply should be bred during the following estrus. If a bitch is Brucella-negative and has aborted several times, a different stud should be used. If that fails, monitoring plasma progesterone concentrations and ultrasonography of the fetuses during pregnancy may reveal a cause. Also, every attempt should be made to obtain a fetus or several fetuses immediately after they are aborted for necropsy and culture.

THE BITCH WITH RETAINED DEAD FETUSES.

Rarely, a bitch is encountered that has dead fetuses in utero. This diagnosis can occasionally be made with abdominal radiography (see Fig. 21-2). The diagnosis is confirmed by using ultrasonography or surgery. Therapy involves ovariohysterectomy or uterotomy and removal of all fetuses. If the bitch has an open-cervix pyometra and the fetuses have undergone autolysis, prostaglandin therapy may be successful if fetal skeletal material is not present in utero. One bitch has been reported with severe hypercalcemia caused by retained fetus and endometritis (Hirt et al, 2000).

DYSTOCIA

Definition

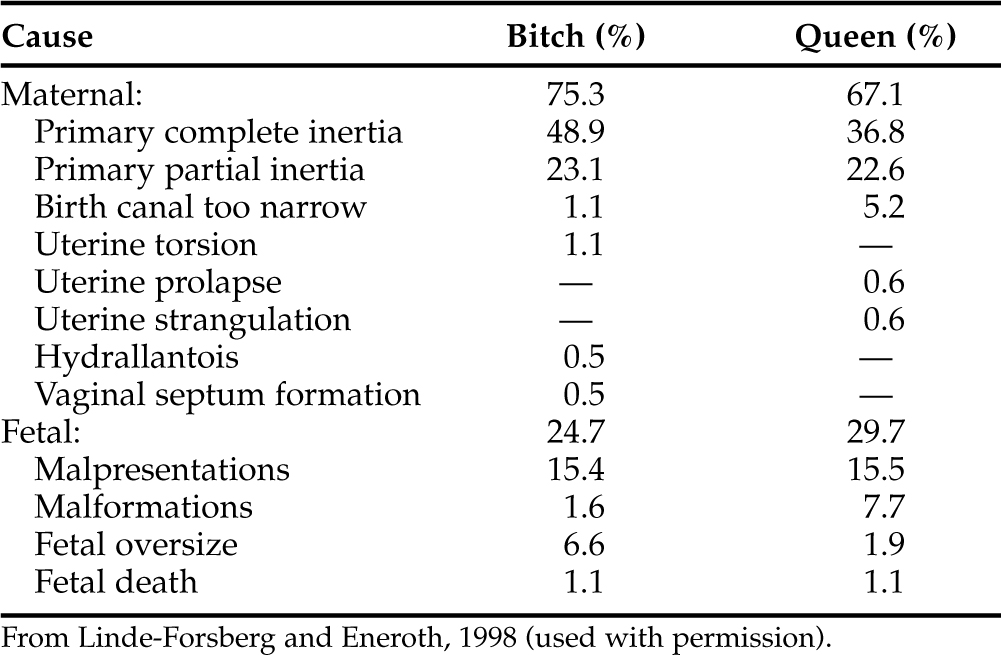

Dystocia is defined as difficult birth or the inability to expel the conceptus from the uterus through the birth canal. Although dystocia is not a common problem in bitches, the condition occurs with enough frequency that veterinarians acquire some familiarity with the condition. However, management of dystocia is not always straightforward. Causes of dystocia are listed in Table 21-2 (Linde-Forsberg and Eneroth, 1998).

Practical Description

THE FETUS.

Occasionally the fetus is too large for the birth canal. The most common explanation for fetal oversize is conception of a single fetus, potentially resulting in a fetus too large for the pelvic canal (Fig. 21-3). Normal “presentation” (posture of the fetus as it enters the pelvic canal) usually results in normal delivery (Fig 21-4, A, B). However, abnormal fetal presentation causes relative oversize. Examples of relative fetal oversize include headfirst presentation with retention of the forelegs, resulting in significantly increased shoulder width (Fig 21-4, C); breech presentation with retention of the rear legs (Fig 21-4, D); presentation of one foreleg and retention of the other; lateral or ventriflexion of the head (Fig 21-4, E, F); or transverse presentation (Fig 21-4, G; Johnston et al, 2001). These problems usually require surgical intervention. Fetal oversize typically does not result from breeding a large male to a small bitch. The bitch usually “dictates” the size of the newborn, whereas both bitch and stud determine adult size of their offspring.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree