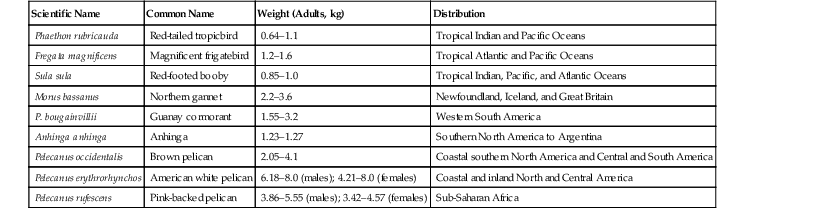

Sharon Redrobe The Order Pelecaniformes was previously defined as comprising birds that have feet with all four toes webbed. Hence, they were formerly also known by such names as totipalmates or steganopodes. The group included frigatebirds, gannets, cormorants, anhingas, and tropicbirds.2 The current International Ornithological Committee classification now groups pelicans with the Families Threskiornithidae (ibises and spoonbills), Ardeidae (herons, bitterns, egrets), Scopidae (hamerkop), Balaenicipitidae (shoebill), and Pelicanidae (pelicans). Previously included families are now classified in the Order Suliformes, that is, Fregatidae (frigates), Sulidae (gannets and boobies), and Phalacrococorcidae (cormorants and shags).3 However, for the purposes of consistency and for this chapter, the previous grouping of Pelecaniformes (pelicans, tropicbirds, cormorants, frigatebirds, anhingas, gannets) will be used with a focus on pelicans (Table 12-1). Most of the birds in this order have large beaks relative to their head size and a distensible pouch formed by the floor of the mouth, between the mandibles. The natural range of the species extends around the world, mainly in the tropical areas. The species most commonly maintained in captivity are the pelicans and cormorants but the others rarely so. TABLE 12-1 Biological Data for Selected Pelecaniformes Adapted from Weber M: Zoo and wild animal medicine, 5th ed, St. Louis, MO, 2003, Elsevier. Chapter 13: Pelecaniformes. The most obvious distinguishing feature of the pelican, besides being large birds, is the gular pouch. The floor of the mouth is greatly enlarged to form the pouch used for scooping up water and prey and then draining the water before swallowing the captured prey. The large beak ends in a pronounced downward facing hook. The tongue is significantly reduced in size. The pelicans are among the largest flying birds and yet are relatively light because of the extensive air sac diverticula between the skeletal muscles of the neck and the breast. These air pockets under the skin are readily palpated when the birds is restrained. The subcutaneous air sacs are known to anatomically connect with the respiratory system, and the bird maintains inflation by the closing of the glottis. The subcutaneous air pockets are presumed to act as a shock absorber when the bird hits the water at speed during a dive and also assist in floating. Males are generally larger than females and have longer bills. Several other species, for example boobies and gannets, as mentioned earlier, also have extensive subcutaneous air sacs. The external nares are not patent in some birds in this order, including brown pelicans, cormorants, boobies, and gannets, perhaps as an adaptation to diving. The rest of the Order Pelecaniformes comprises long-legged birds that hunt or scavenge prey near lakes or rivers and are relatively slender in body shape. The gular pouch is used for courtship displays in frigatebirds and absent in the tropicbirds. Birds of this order are typically carnivorous (primarily fish eating). The proventriculus and the ventriculus are both thin and extensible in the pelican and cormorant species and relatively indistinguishable. The pylorus is very well defined and well muscled, and this may be an adaptation to prevent foreign bodies and bones entering the small intestine. In common with many other marine species, Pelecaniformes typically have supraorbital salt glands that may atrophy in captivity if they are housed on fresh water. When birds are transferred between institutions, the salinity of the water should be noted, and it must be ensured that the birds are transferred between the same systems; in the case of transference from a freshwater environment to a saline environment, supplementation with dietary salt (if a pool of increasing salinity cannot be provided) should be carefully instigated to reactivate the salt glands without risking salt poisoning. The birds should be carefully monitored during this process. This process should also occur prior to release from a freshwater or a low-salt facility. Birds in this order are characteristically semi-aquatic birds that dive from a great height into water to capture prey. It may be challenging to replicate this behavior in captivity, but the birds should certainly be provided with pools that permit swimming and surface diving. Maintenance of adequate water hygiene, using appropriate surface skimmers and other measures, will be required to prevent the accumulation of fish oils damaging the feathers. Sufficient dry land area is required, especially for pelicans, cormorants, and anhingas, which have feathers that tend to get waterlogged. The substrate needs to be supportive and noninjurious, as all birds in this order, particularly the heavier species, are prone to pododermatitis. The natural diet of pelicans is quite varied and related to their aquatic habitat, including fish (up to 30 centimeters [cm] long), crustaceans, amphibians, turtles, and occasionally other birds. The way different species of pelican feed varies. For example, the brown pelican feeds by diving into water, whereas the white pelican species feed cooperatively by herding fish and dipping their beaks into the water to scoop the fish out. Cormorants and anhingas are surface divers and capture their prey underwater. Tropicbirds, boobies, and gannets are plunge divers. Frigatebirds are renowned scavengers and steal food from other birds. Birds in captivity need to adapt to taking dead fish, and training may be required when presenting the fish in a manner dissimilar to their wild presentation. Throwing fish into the air is the least natural presentation of fish, but the movement may stimulate attack and feeding. If feeding fish that has been frozen, supplementation with vitamins is often required; further information on fish handling as food and supplementation will not be covered in this chapter. In general, restraint of these species is simple, with the birds being captured in a net or herded into a corner, the beak restrained in one hand initially, and then the body and wings restrained under the other arm. As the nares are not patent in some species (brown pelicans, cormorants, boobies, and gannets), the beaks should be held slightly open during restraint to prevent asphyxia. When stressed, some birds (gannets and pelicans) may inflate their subcutaneous air sac diverticulae that may easily be palpated by the handler as crepitus under the skin; this may be an alarming finding to the novice. Staff should consider wearing eye protection when handling birds such as the anhingas, which have long sharp beaks. Inhalant anesthesia using isoflurane is a simple and easy way of anesthetizing Pelecaniformes. The long beak makes application of a mask difficult; a useful tip is to use a disposable rectal glove as a makeshift mask for induction. Pelecaniformes are easily intubated with an uncuffed endotracheal tube. Nitrous oxide should be avoided because it has been reported to cause significant expansion of the subcutaneous air sacs of a pelican.9 Endotracheal intubation of some species may be challenging because of the crista ventralis, a septum or projection across the lumen of the trachea just inside the glottis. Intubation is readily achieved using a smaller tube, with the awareness that the inhalation anesthesia may be less efficient and the bird will also be breathing room air, that the airway is less protected, and that assisted ventilation will be less effective. As with other bird species, the addition of ketamine (3 milligrams per kilogram intramuscularly [mg/kg, IM]) and butorphanol (1 mg/kg, IM) provides more controlled anesthesia suitable for surgery and endoscopy (personal communication, author). Surgery, particular to this group of birds, is performed for repair of the pouch.12 Special considerations include establishing that subramal and ventral gular blood supply is intact, as no evidence of anastomoses between these vessels exists, so vascular damage to these areas may result in poor wound healing. Full thickness suture patterns should also be avoided when repairing laceration of the pouch to avoid compressing the vascular layer. The pouch should be repaired by separating the epithelial layers and suturing them separately using a simple interrupted pattern. Flight is often restricted in the larger species such as pelicans, as their size necessitates very large (and relatively expensive) meshed aviaries to permit free flight; they are therefore often restrained in large, open-topped areas by such methods as feather clipping, feather follicle extirpation, or pinioning. Clinicians should note that in some countries, pinioning (amputation of the wing tips) is legally performed by nonprofessionals in very young birds. In other countries, pinioning is legally restricted; for example, it is considered “an act of veterinary surgery” in the United Kingdom and, as such, may only be performed by a veterinary surgeon (on a bird of any age) and must be performed with the bird under general anesthesia if the bird is over 10 days old. Currently, few publications on pelican surgery exist in the literature, but a case of successful keratoplasty performed on the left cornea of a young adult female California brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) for the treatment of vision-threatening corneal scarring has been reported.5

Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds, Cormorants, Frigatebirds, Anhingas, Gannets)

Biology

Scientific Name

Common Name

Weight (Adults, kg)

Distribution

Phaethon rubricauda

Red-tailed tropicbird

0.64–1.1

Tropical Indian and Pacific Oceans

Fregata magnificens

Magnificent frigatebird

1.2–1.6

Tropical Atlantic and Pacific Oceans

Sula sula

Red-footed booby

0.85–1.0

Tropical Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans

Morus bassanus

Northern gannet

2.2–3.6

Newfoundland, Iceland, and Great Britain

P. bougainvillii

Guanay cormorant

1.55–3.2

Western South America

Anhinga anhinga

Anhinga

1.23–1.27

Southern North America to Argentina

Pelecanus occidentalis

Brown pelican

2.05–4.1

Coastal southern North America and Central and South America

Pelecanus erythrorhynchos

American white pelican

6.18–8.0 (males); 4.21–8.0 (females)

Coastal and inland North and Central America

Pelecanus rufescens

Pink-backed pelican

3.86–5.55 (males); 3.42–4.57 (females)

Sub-Saharan Africa

Unique Anatomy

Special Housing Requirements

Feeding

Restraint and Handling

Surgery and Anesthesia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree