CHAPTER 19 Parasitic and Protozoal Diseases

Young animals are commonly at risk of a variety of parasitic infections, and morbidity and mortality rates are typically higher than in adults. Resistance to parasitic infection is weak in pediatric patients, as the immune system is not fully developed and the relative parasite burden is high. Successful management depends on a working knowledge of parasites and their life cycles, diagnostic techniques, appropriate therapeutics, and preventative strategies. The information in this chapter is intended as a brief overview of parasitic diseases encountered in puppies and kittens. It is not intended as a comprehensive list of all possible parasites. The list of Suggested Readings at the end of the chapter is a guide to more complete discussions. General guidelines concerning parasite control in dogs and cats are summarized in Box 19-1.

BOX 19-1 New 2008 CAPC general guidelines for controlling internal and external parasites in U.S. dogs and cats*

Parasite Control Should Be Guided by Veterinarians

Every Pet, All Year Long

Healthy Lifestyle, Healthy Pets, Healthy People

If Less Than Optimal Control Is Practiced

* From CAPC website: http://capcvet.org/recommendations/guidelines.html. (Accessed 12-8-09.)

Gastrointestinal Parasites

Helminths

Roundworms (Ascarids): Toxocara canis, Toxocara cati, Toxascaris leonina

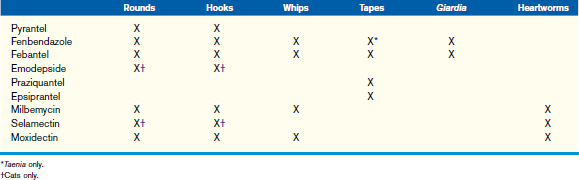

A number of effective anthelmintics are available (Table 19-1). Deworming is ideally started at 2 weeks of age and repeated every 2 weeks for four treatments. Following this, certain heartworm preventatives will control roundworms if continued year-round (see Table 19-1). Prenatal infection with T. canis can be prevented in puppies by daily administration of fenbendazole to pregnant bitches starting at day 40 of gestation and continuing through day 14 postpartum. Selamectin also prevents prenatal transmission in puppies if given at days −40, −10, +10, and +40 before and after whelping. Similar studies have not been reported in cats. Roundworm ova persist in the environment for months and possibly years. Removal and proper disposal of feces at least twice a week will decrease the risk of soil contamination.

Hookworms: Ancylostoma caninum, Ancylostoma tubaeforme, Ancylostoma braziliense, Uncinaria stenocephala

Adult hookworms are rarely excreted, so diagnosis depends on identifying ova by fecal flotation.

Many anthelmintics treat both hookworms and roundworms (see Table 19-1). An appropriate schedule for puppies and kittens is every 2 weeks starting at 2 weeks of age for four treatments. Monthly deworming may be continued using heartworm preventatives. Perinatal infection in puppies can be avoided using daily fenbendazole in pregnant bitches from day 40 of gestation through day 14 postpartum.

Whipworms: Trichuris vulpis

Several anthelmintics are effective against whipworms (see Table 19-1). Fenbendazole and febantel are commonly used, although monthly heartworm preventatives containing milbemycin and moxidectin can be used for treatment and control of recurrent infections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree