Debra C. Sellon

Pain Management in the Trauma Patient

Historically, pain management for horses undergoing major surgery or experiencing significant trauma has been implemented as much for purposes of restraint and human safety as for patient health or physiologic benefits. In recent years, human injuries sustained in global conflicts have served as a catalyst for major advancement in understanding and treatment of trauma-related pain. It has become apparent that poorly managed acute or chronic pain can have a profoundly negative effect on patient recovery and return to normal function.

Pain in the Trauma Patient

Nociception is the detection and perception of pain caused by potentially tissue-damaging stimuli. It occurs through the processes of transduction, transmission, modulation, and perception of noxious stimuli. Chemical (inflammatory), thermal, or mechanical stimuli activate local nociceptors (transduction). Action potentials are transmitted along sensory nerves into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and from there are relayed to higher brain centers (transmission). At each step in the process, there is an opportunity for nociceptive impulses to be potentiated or inhibited (modulation) before they reach the somatosensory cortex, where perception occurs. The severity of pain perceived following an injury can vary widely depending on the type of modulation that occurs at the site of the injury, within the spinal cord, and within the higher brain centers. Inflammatory mediators released at the site of injury sensitize nerve endings, making them hyperresponsive to noxious stimuli (primary or peripheral sensitization). Neurotransmitters released within the spinal cord increase excitability of neurons at that level, resulting in secondary or central sensitization. Sensitization at the level of the spinal cord and brain can result in long-lasting changes in pain perception and influence development of chronic pain states. Rapid administration of appropriate analgesic therapy can lessen the degree of primary and secondary sensitization that occurs, diminish the overall pain experience, and hasten healing and return to function.

Uncontrolled pain can have a number of adverse effects. Much of the current knowledge of the role that pain plays in overall health and healing after injury or illness arises from investigations into the importance of postoperative pain in the recuperative process after surgical interventions in species other than the horse. Pain responses are an important part of an overall neurohumoral stress response that is also influenced by anxiety, fluid loss, hemorrhage, systemic inflammation, and infection. The stress response induces neural, endocrine, immune, hematologic, and metabolic changes that are intended to restore homeostasis. Sympathetic activation triggers increases in heart rate and blood pressure and inhibits gastrointestinal motility. Acute pain inhibits respiratory function, resulting in decreased tidal volume and alveolar ventilation, which can lead to ventilation-perfusion mismatch and impaired pulmonary gas exchange. Alterations in release of cortisol, insulin, glucagon, and other stress hormones lead to a catabolic state characterized by hyperglycemia, lipolysis, and protein catabolism, with resultant weight loss and impaired wound healing. Humoral and cellular immunity are inhibited during the surgical stress response because of sympathetic stimulation, increased cortisol release, and endogenous opioid activity. The beneficial effects of decreasing the postsurgical stress response through provision of adequate postoperative analgesia have been extensively investigated in human patients. Benefits may include improved wound healing, fewer cardiopulmonary complications (heart attack, thromboembolism), decreased risk for gastrointestinal ileus, decreased risk for pneumonia, decreased hypercoagulability, fewer postoperative infections, less weight loss, and shortened time to discharge from the hospital.

There is a dearth of available information regarding the impact of analgesia on recovery after surgery or trauma in horses. In one study, horses receiving a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) and an opioid (butorphanol) recovered better after surgery than did horses receiving only an NSAID (Sellon et al, 2004). Horses with multimodal analgesia lost less weight after surgery and were discharged from the hospital earlier than control horses. These findings are consistent with reports of hastened recovery after abdominal surgery when human patients receive adequate postoperative analgesia. Additional equine studies are needed to confirm these results and determine the significance of the role that pain may play in morbidity and death in horses after trauma or major surgery.

The degree of pain experienced can vary among individual horses, even if the nociceptive stimulus is the same. This experience of pain depends on such factors as age, genetic background, sex, prior experiences, socialization, training, and stress level. It is therefore very difficult to accurately assess the degree of pain that any individual animal is experiencing. To develop an acute pain management plan, the clinician must be knowledgeable about the nature and consequences of uncontrolled pain, condition of the individual patient, and mechanism of action and potential adverse effects of available analgesic agents.

Pain management after acute trauma can be especially challenging because of concomitant problems, including volume depletion, extreme activation of the sympathetic nervous system, cardiovascular and respiratory dysfunction, and shock. An accurate assessment of volume status, cardiovascular function, and respiratory function is essential for making appropriate choices regarding drugs and dosages for any individual horse. Just as the nature of the pain experienced by each patient is unique, the pain management plan for each patient should be unique. Whenever possible, the plan should include a combination of drugs that act at different sites in the nociceptive pathway to simultaneously modulate pain processes that are active peripherally and centrally.

Analgesic Options

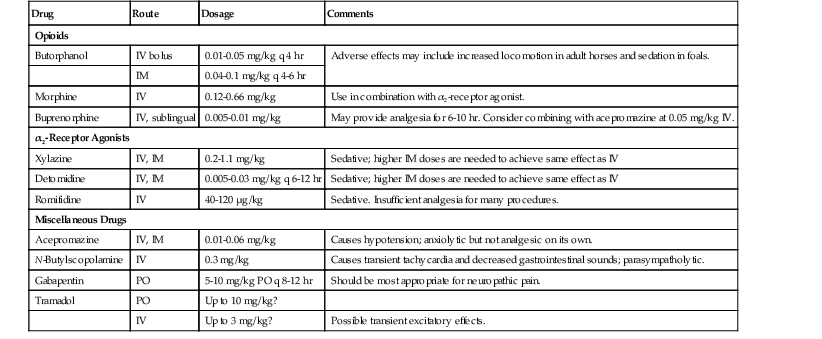

Since the American Civil War, intravenously administered morphine has been the primary analgesic agent used for immediate pain relief in soldiers with battlefield trauma. In contrast, veterinarians have relied primarily on intravenous NSAIDs supplemented with α2-receptor agonists and opioids to achieve immediate restraint and analgesic effects after traumatic injury in horses. Recommended dosages for analgesic agents that may be used in horses are summarized in Tables 2-1 to 2-3. The appropriate dose may vary greatly between individual horses, depending on the circumstances and condition of the horse.

TABLE 2-1

Commonly Used Analgesic Agents (Excluding NSAIDs) and Suggested Dosages in Horses*

| Drug | Route | Dosage | Comments |

| Opioids | |||

| Butorphanol | IV bolus | 0.01-0.05 mg/kg q 4 hr | Adverse effects may include increased locomotion in adult horses and sedation in foals. |

| IM | 0.04-0.1 mg/kg q 4-6 hr | ||

| Morphine | IV | 0.12-0.66 mg/kg | Use in combination with α2-receptor agonist. |

| Buprenorphine | IV, sublingual | 0.005-0.01 mg/kg | May provide analgesia for 6-10 hr. Consider combining with acepromazine at 0.05 mg/kg IV. |

| α2-Receptor Agonists | |||

| Xylazine | IV, IM | 0.2-1.1 mg/kg | Sedative; higher IM doses are needed to achieve same effect as IV |

| Detomidine | IV, IM | 0.005-0.03 mg/kg q 6-12 hr | Sedative; higher IM doses are needed to achieve same effect as IV |

| Romifidine | IV | 40-120 µg/kg | Sedative. Insufficient analgesia for many procedures. |

| Miscellaneous Drugs | |||

| Acepromazine | IV, IM | 0.01-0.06 mg/kg | Causes hypotension; anxiolytic but not analgesic on its own. |

| N-Butylscopolamine | IV | 0.3 mg/kg | Causes transient tachycardia and decreased gastrointestinal sounds; parasympatholytic. |

| Gabapentin | PO | 5-10 mg/kg PO q 8-12 hr | Should be most appropriate for neuropathic pain. |

| Tramadol | PO | Up to 10 mg/kg? | |

| IV | Up to 3 mg/kg? | Possible transient excitatory effects. | |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree